There are two stimuli our economy can count upon before Christmas. One is the economic recovery plan which will be presented in parallel with Budget 2021. The other is the stock of private savings, now at record highs thanks to the high levels of fear and uncertainty in our economy, and the inability of many households to actually spend their money the way they would like.

The economic recovery plan will be sectorally specific and if the state can credibly borrow at near-zero rates for long enough, should be massive. The savings of households will be directed through the channels that best meet consumers’ needs.

There is a deep inequality here: Not everyone has been able to save, but those who are lucky enough to have spare dosh will either use it to pay down their debt, making them less fragile for the coming phase of the crisis, or use it to save for a specific purpose. That specific purpose might well be households spending a lot when they can.

If there is any historical precedent, it is the Emergency years of World War Two. From 1938 to 1944, household expenditure on clothing, fuel, and other goods fell between 50 per cent to 60 per cent due to rationing and shortages. People simply saved. When the war was over in 1945, consumers spent their pent-up savings, resulting in a consumer boom in the post-war years. There is no reason to believe 2020 will be much different from 1945, except for one key difference: the Internet. It has become a second channel to funnel purchases, in addition to the usual bricks and mortar we grew up with.

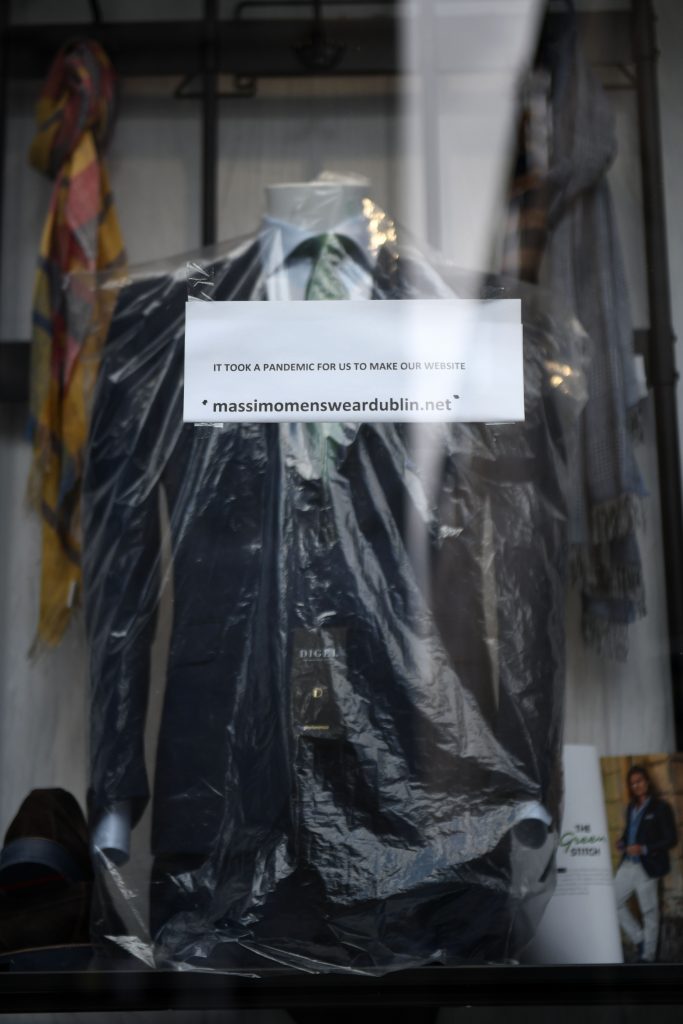

The post-Covid analogue to the Brexit preparation policy is moving firms online and into different marketplaces as quickly as possible.

Which channel will be more important to the recovery? Will it be bricks or clicks? Let’s do a thought experiment.

Imagine for a moment that, through some law or technological hurdle, no commerce could be transacted through the internet. None at all. Now allow the wall holding savings back – which again is just really fear of a Covid-tainted future – to fall. Where does the money flow? It flows into the coffers of retailers on high streets, and stores of all kinds. People buy durables like fridges and cars, they buy clothes, they buy, buy, buy whatever they need, really. The result is an employment boom and a profit boom for retailers and every kind of organisation selling something.

Reverse the thought experiment now. The high street is banned somehow, and the only plumbing that can take the flow of funds from savers to our businesses is via the Internet. Where does the money go? It goes to organisations all over the globe, some of which are surely Irish, but most of which will probably be large online retailers like Amazon.

In this world of online-only, the stimulus is only effective for the Irish economy and for jobs if Irish firms are online to benefit and if the service can be bought or sold online. Many are, of course, but many are not.

In the run-up to Brexit, the government produced many resources to help impacted firms access new markets beyond the UK. The post-Covid analogue to the Brexit preparation policy is moving firms online and into different marketplaces as quickly as possible. Here, we encounter two large problems, and they are real-world issues our thought experiment cannot get away from. First, even if one could move our Covid-affected businesses onto the net, the regulatory barriers these firms have to overcome are considerable.

A white paper based on a survey off Stripe’s customers found two thirds of business leaders claimed they would be active in at least 10 more countries if either regulations or tax regimes were better harmonised across the EU. Think about the extension of the market for an Irish firm if this were to be achieved.

Some 72 per cent of businesses they surveyed felt compliance with country-by-country regulations is a hindrance to their growth, including 30 per cent who stated it is “a great challenge”. On average, businesses felt they could increase revenue by an enormous 30 per cent if they did not have to deal with regulations and compliance. Regulations spanned from industry-specific regulations, safety regulations, identity and user verifications, VAT management, taxes, privacy regulation, accounting and HR standards, and payments regulations.

Levelling the playground

Not surprisingly, Stripe advocates a mixture of technology-based solutions and legal harmonisation. The companies that figure out how to level the playgrounds for their fellow entrepreneurs are going to make a fortune because they will solve a large problem our retailers have right now. The key policy problem is how quickly new markets can be opened up.

Covid-19 restricts the number of people who can consume using bricks and mortar shops, and worse, it drives up the cost of acquiring new business. The table below from the recent Stripe report shows the top three business problems identified by more than 500 respondents, both pre and post the introduction of Covid-19. What do we see?

We see 56 per cent of respondents worrying about sales, as opposed to 44 per cent pre-Covid. We see 59 per cent concerned with keeping cost down now, a huge jump from 37 per cent. Concern with regulation and compliance costs have risen as well, from 26 per cent to 32 per cent.

The report found only 33 per cent of businesses were fully confident that they are compliant with regulatory standards, while only 26 per cent were confident they fully understand which regulations affect them.

I mentioned the problem of large firms hoovering up the savings supplied by consumers, especially online. Large firms concentrate power and thus the ability to command large margins.

A paper published in the Review of Finance by Gustavo Grullon and colleagues looked at the reasons behind the increasing concentration in more than 75 per cent of US industries, where the average increase in concentration levels have reached 90 per cent. The market share of the four largest public and private firms has grown significantly for most industries. Both the average and median sizes of public firms – the largest players in the US economy – have tripled in real terms since the 1990s.

Increasing concentration levels really does a number on margins. Grullon and his team found a change in concentration levels increases profit margins by 142 per cent relative to its median level. That is, it surely doesn’t need saying, a lot of money. The upshot is firms in concentrated industries are becoming more profitable mostly through higher profit margins, rather than via greater efficiency.

Grullon’s research shows us it is not geniuses or wonderful management tactics, but the unique combination of lax enforcement of antitrust laws in the US and technological innovation. Each created giant barriers for new entrants into markets to leap over.

Ireland’s SMEs need a package of measures to get them online and trading quickly. They are responding to that themselves. The ability to trade across borders, especially post-Brexit, will be vital in keeping many of them afloat. Regulatory harmonisation, and the smoothing out of the differences between markets using technology, is a deeply boring but deeply important problem for our policymakers to help solve.

There is a profit motive in making regulations work at the same level, but there is also a public good argument. When two standards are harmonised, picking the better standard can often result in a better outcome for the consumer, and the planet, not to mention levelling the playing field for Irish firms abroad by sponsoring the creation of a digital single market.