Yvonne Burke is the chief financial officer of Glen Dimplex, the Irish consumer goods giant. It is a major role in a major company that is working on major projects. Yet, she has maintained a distinctly low profile.

“I’ve never done anything before,” she said when Tom asked her about her media experience when he interviewed her earlier this year. “Apart from the school magazine, that’s about it.”

Yet, over the next hour, she told her own fascinating story and gave insights into one of Ireland’s most significant companies. “I like playing a number of roles. I don’t like staying in my lane,” she said.

Burke was one of hundreds of people we interviewed over the past year. Some were entrepreneurs. Some were policymakers or politicians. Some led newly conceived start-ups, while others led semi-state giants or publicly listed companies.

With all, we tried to be inquisitive, fair, and thorough. We try to ask questions that will elicit the most informative response and to give the interviewee the room and scope to answer questions. We don’t always get it right, but that is our aim – to talk to interesting people about interesting topics and to let them speak.

Here is a selection of interviews from the past year that we think you might enjoy.

“When your life has been defined by building companies, it does tend to be how you think about the future”

For more than 20 years, Dylan Collins has been building businesses that have been repeatedly gobbled up by tech behemoths. His most recent venture, undoubtedly the most triumphant yet, was SuperAwesome. The company set about making the internet safer for kids and was acquired by Fortnite developer Epic Games in 2020 in a deal worth just under $500 million.

After a decade at the helm, Collins decided to call time at SuperAwesome last year. Now, he’s in a period of recharging and what he calls “Gandalf-ian wandering”, in reference to the iconic wizard from the Lord of the Rings. Before penning a series of articles for The Currency, Collins sat down with Michael Cogley in London.

“I think when your life has been defined by building companies, it does tend to be how you think about the future,” Collins told Michael.

“It is fun to build and, quite frankly, a lot of founders and entrepreneurs struggle with living in a low-status way of not being a founder, not being a builder when you spend so much time in this ecosystem, which is essentially defined in very binary terms: You’re either an investor or a builder, or you don’t really exist.

“However successful you’ve been, if you’re not labelled as one of those things, I think psychologically – and this is pure ego – it can be tough for people and I think that’s why you see people running into things quite quickly.”

Michael Smurfit on life, deals, and industry: “We’ve built brick on brick, year on year, decade on decade – not overnight”

Michael Smurfit was sitting at a set table to the right of the entrance of the Lady Ann Magee yacht when Tom arrived in Monaco to interview him. The industrialist had a bottle of fine wine open to breathe and one of his staff opened another equally fine bottle of wine as Tom sat down. Behind Smurfit were three photographs: one with his close friend Prince Albert of Monaco, and the others of his family. Over the hours that followed, they talked about many things: life, business, family, money.

This was all detailed in a fascinating portrait of Michael Smurfit. “I never had a moment in my life when money didn’t count,” Smurfit told Tom. “But in line with my growth, with my wealth and the company’s growth, I kept my feet on the ground, I think.”

Smurft took Tom through the rise of the Smurfit group, and the deals that copperfastened his legacy as Ireland’s greatest CEO. But he also showed a human side, particularly when he reflected on age and mortality.

“I’ve no idea where I’m going. I know it’s a one-way trip. It’s a one-way trip for everybody. I’m alone on the bandwagon. I’m the last of the Mohicans, nearly, with all the group of friends I had in my life in Ireland.”

As Tom noted, building a global business is very hard, something few Irish business leaders have managed.

“It is almost impossible to become number one at something that a lot of people do in every country. The odds are stacked against you,” Tom wrote. “Yet, it is something the Smurfit family has done.”

Building on a legacy: “It’s in memory of Pino. That’s why I did it”

Life could have been so different for Denise Harris. Family tragedy crushed the dream of opening her very own styling and beauty boutique in Dublin in the late 1970s, the very morning that she was due to cut the ribbon on her entrepreneurial future in the capital city.

Her father had been in a serious car accident and badly damaged his leg. He was told that he wouldn’t drive again. As a livestock exporter, he needed to be able to get from place to place. It was core to the business.

Harris put her plans on hold and dedicated herself to her father, driving him where he needed to go and putting her all into supporting him in the trade.

However, as Niall explained, it was this misfortune, coupled with her undying love and loyalty to her father, that set her on the track to where she is today: heading up the Harris Group, the largest retail sales and parts distribution centre for commercial vehicles in the country.

Heading up the Harris Group was never in her plans. But it was certainly something that her late husband Pino had thought about, as Harris learned when she took herself off to the solicitor. She needed to find out what he had wanted for the company, so that she could let workers know about their futures.

“I never anticipated anything like that would happen, so I never asked him what way things were,” she says. “I just went in and asked [the solicitor] what way the company was set and he said, ‘You are now the company’.”

“We’re back to bootstrapping, but we’re doing better than ever”

At the UCD Smurfit School Business Journalist Awards in November, Thomas scooped the gong for Business Interview of the Year for his piece with the entrepreneur Tom Cotter. It was a deserved reward for a fascinating article.

In 2016, Tom Cotter began toying with the idea of making clothes for water sports enthusiasts. Eight years of hard knocks followed. As he told Thomas, he was once on the point of giving up but fate gave him a break and put him in touch with a leading Cork businessman who has remained one of OceanR’s main backers to this day.

The company now employs over 70 people. When they sat down, Cotter was preparing a crowdfunding campaign, explaining how the this just a stepping stone towards bigger plans as OceanR is about to break even. But he was also very candid about the unusual entrepreneurial career that led him to this point, his business self-education through repeated trial and error, and the tragedies he faced along the way.

He hadn’t told the whole story until this interview with The Currency.

Cotter says learning how much it takes to grow this business to each new level has given him an understanding of how to do it sustainably, avoiding the temptation to raise funds and plough them into over-hiring. “We’re back to the bootstrapping stage, but doing better than ever,” he says. “We know what we’re doing. What it’s about now is just tweaking, hiring one or two salespeople to notch it up incrementally rather than trying to double revenue in six months.”

Paranoia, complacency and Stripe: Inside the mind of John Collison

John and Patrick Collison have built one of the most valuable private companies in the world – some analysts put Stripe top of the rankings.

The fintech giant was valued at $70 billion after a recent share transaction, a figure that is up on a $50 billion low last year, yet down on its peak $95 billion 2021 valuation.

The brothers are billionaires many times over. Despite spending much of their time in the US, both have retained deep connections with Ireland.

That was obvious in my interview with John Collison, the Stripe co-founder and president. Collison readily agreed to an interview on Ireland and its place in a rapidly evolving world and, over the course of an hour, he delved into everything from the housing crisis to the rights of ramblers across rural Ireland.

He is enthused about the country’s potential. As he puts it, the headwinds are in Ireland’s favour.

But he is concerned about the blockages to crucial infrastructure such as energy and housing. He calls for a more public conversation over how the wider planning system works and how Ireland makes decisions.

He points to IDA Ireland, something he describes as a “radical idea of its time”, and Ireland’s subsequent corporate tax strategy.

“It is funny to imagine trying to introduce the corporate tax policy that caused so much prosperity in Ireland in today’s environment. The debates would do your head in over it,” he said.

“We had all these radical ideas that worked. Now we are failing at a bunch of major investment ideas. It would be okay if we were failing and were really unhappy about it as a country. But we are failing at these opportunities and people seem to be okay about it.”

It was a prescient warning from a man who has invested deeply in Ireland.

Thirty years and still facing its “biggest opportunity”: Inside DCC’s constant evolution

DCC is one of the most consistently profitable and quietly remarkable businesses in corporate Ireland. It employs 16,000 people, has revenues of £20 billion (€23.8 million) and its dividend policy is superb. It is making more money from the green transition than most comparable businesses.

In May, analyst Rory Gillen described its record of growth as “on a par with the iconic Berkshire Hathaway”.

Gillen concluded that perhaps only half a dozen European companies have been able to grow as much over the same 30-year period.

And yet, as Tom reported, it is unloved by the stock market. In fact, I would bet most people in Ireland would struggle to tell you what it does.

Yet, it does it successfully. Tom sat down with its chief executive Donal Murphy to understand what other businesses can learn from its longevity, and its capacity to quietly, and consistently, evolve.

The great challenge for DCC and Murphy is to convince the market of its value. “If we look back in 10 years’ time and we have succeeded and delivered on our objectives, we’ll have a phenomenal business that has really impacted climate change issues for the better,” Murphy told Tom.

In November, some months after the interview was published, the company said it planned to sell its healthcare division in 2025, review its “strategic options” with its technology business within 24 months and focus on its “largest growth opportunity” – energy transition. DCC’s shares surged on the news, closing up 17 per cent.

In a follow-up interview that day, Tom asked Murphy about the change of course. “If I’m really open, it was probably sitting on the beach on my holidays, after we talked. This was always about timing, and I fundamentally believe this is the right time to do this,” according to Murphy.

“The board wanted to fundraise more; I wanted to sell. I knew I wanted to move it along”

Two years ago, Aisling Teillard was facing a dilemma. Teillard wanted to sell Our Tandem, the employee management firm she had co-founded in 2015. Teillard had nursed the company through Covid when a host of major contracts dissipated, and through the Russian invasion of Ukraine (where 70 per cent of the company’s staff were based). The entrepreneur felt she had taken the business as far as she could. The board, however, thought otherwise and wanted to raise more money to accelerate the company’s expansion.

Ultimately, they reached a middle ground. “So what we agreed was a parallel run – we would appoint a corporate finance advisor to look for sale and investment opportunities. We would sell both stories and see what was the best offer,” she said.

Ultimately, the company was sold to beqom in Switzerland, and Teillard moved to that country to take up a wider role.

“Two of the three bidders had approached me directly outside of the corporate finance advisor,” she said.

One of them was from beqom: “We had done a commercial partnership with them already. I said to them, ‘Look, we are going up for sale. So you want to just make this a sale rather than a partnership? And he said yes.”

“My focus is definitely on moving more into Ireland”: London PE firm Lonsdale Capital on its Irish ambitions

In another life, Ross Finegan may have been better known for his exploits on the rugby pitch than his sterling investing career.

The 54-year-old Dubliner worked his way up through the Irish schools system and earned a brace of full Leinster caps before a gruesome knee injury brought his playing days to a skidding halt.

“I had my leg planted in the ground and I was tackling somebody else and his whole hips came around at pace and the knee went backwards and inwards,” he told Michael.

Instead, he made his way in the world of commerce, doing stints in the corporate finance arms of Deloitte and JPMorgan before establishing his own mid-market private equity firm, Lonsdale Capital Partners, in 2009.

The private equity firm invests between £10 million (€12 million) and £20 million into businesses touting enterprise values that range from £20 million to £50 million. Lonsdale typically backs services and healthcare companies across both the UK and Ireland.

Finegan set up the fund alongside David Gasparro, a former distribution chief at US asset manager Threadneedle, and Alan Dargan, a former MD at Credit Suisse First Boston.

When asked whether there were lessons to be learned from Britain’s economic prowess, he countered that there are, instead, some things that can be learned in Ireland and brought to the UK.

“It’s not as if I regard the UK as ahead of Ireland,” he says. “I’m 30 years in the UK and I actually think that Ireland is potentially ahead of the UK when it comes to a better environment for business growth.”

“Lean in early. Lean in big. Take a lead. Your competition is always trying to chase you”

It is hard to grasp the scale of Accenture. It is the world’s third-largest private-sector employer with 774,000 people. In Ireland, it is one of our biggest private sector employers with 6,500 people. It has four offices here; the Dock and a second location nearby in Dublin’s docklands, as well as Accenture Song in Smithfield plus an office in Cork to service the Munster region. It has bought two companies in Ireland; Rothco, which became Droga5 Dublin and is now part of Accenture Song, in 2018 and ESP in 2019.

Sitting at the top is Hilary O’Meara, the country managing director of Accenture in Ireland.

When she sat down with Tom in November, O’Meara talked about the importance of creativity, Ireland’s role in a rapidly changing world, and the transformative power of AI.

As part of the interview, she gave Tom a tour of Accenture’s GenAI studio, one of 25 such centres it runs globally to service clients including some of the world’s biggest companies.

The studios are the visible part of a $3 billion investment by Accenture in all things AI, a drive that the firm has said will see its employees in this area increase from 40,000 to 80,000 people out of its global workforce of nearly 800,000.

The studio opened 18 months ago and initially, its focus was on educating clients about what was coming, but now things have moved on. “Now it is about what is the path to scaling use cases,” she said.

“This is a proper studio. It is not window dressing. It is a mix of both our best-in-class from around the world and it also helps our R&D team develop assets for our clients.

“We invest big, and we invest early. We are embedding AI into the tools that we are developing for our clients. This studio is about working with our clients, disseminating it, finding golden nuggets, and pushing that into the hands of our clients globally.”

“We’re entitled to our own opinions, but not to our own facts”

Judge Richard Humphreys was wearing his formal robes in preparation for the photographs that accompanied this piece, but removed them as soon as the shoot was finished, sitting at a round wooden table for the interview with Alice in a worn shirt, wool jumper and jacket.

As Alice put it, it’s fitting for a man who says he aims to bring a level of informality to the new court over which he presides: the Planning and Environmental division of the High Court.

A year old, it is quickly becoming one of the busiest arenas in the Four Courts. The court has three judges: Judge Humphreys who leads it, Mr Justice David Holland; and Ms Justice Emily Farrell who was assigned last year. Since October last year, it has seen a 73 per cent increase in the number of cases.

When the court was established, the Courts Service said that one judge was required for every 50 to 60 live cases. With over 240 live cases, the demand for the court has already exceeded the capacity of its three judges.

“The question of resources, it’s above my pay grade, but, I mean, it’s there for the powers that be,” said Judge Humphreys.

“We live in interesting times, there’s still an awful lot of moving parts,” he continued. “But I’d be reasonably hopeful and confident that people will want the planning environment court to succeed. And we’ll keep all that under very active review.”

“It’s an interesting area, that’s the blessing of it,” he says.

Peter Sweetman: “Every case I take is based on the incompetence of Ireland”

Over the last three decades, the name Peter Sweetman has become well known – for some almost too well known – in environmental, political, planning and legal circles.

The prolific environmental litigant has his admirers for his approach to challenging decision-making in the planning system out of line with strict EU laws, designed to protect the natural world at large.

But the Kildare native also has a long line of detractors over what has been described in some quarters as a scattergun approach to taking cases and subsequent delays to infrastructural and commercial projects.

As he told Niall in a rare interview, he has one answer to them all: The law is the law.

“The EU makes the law, and if they make the law, that’s the law. It’s not my business, I don’t question the law. I implement the law,” he argued from his adopted rural home on the Atlantic coast of Co Mayo.

In a frank and open interview, he spoke candidly about 30 years at the coalface of environmental litigation, the legacy of his biggest cases, the criticism of his tactics and how, even at the age of 82, he still has more left in the tank.

“Who cares if you fail? You learn by your failures. We’ve tried loads of things and failed”

At first inspection, it is difficult to trace the lines of the various divisions within Tarasis Enterprises, the Co Armagh-registered holding company for Mairead Mackle’s business empire.

However, the more Mackle explains it, the more it makes sense.

She started out with Homecare Living (since rebranded as Tarasis Healthcare). From its origins in her living room, the business now provides more than one million hours of in-home care services to 60,000 people across Ireland each year.

This division led to another, Tarasis Housing, which provides thousands of crisis beds every night in Ireland, as well as producing eco-friendly, modular space solutions to help tackle housing shortages.

Mackle then began examining the socio-economic reasons people needed emergency beds. Tarasis Support Services was born, with the ambition of helping people not to become homeless.

In 2011, after selling some shares in her Homecare business, she launched a renewable business that has since built two biomass plants.

And this led her to Wagyu beef production. “All of our companies have that common thread of social impact. We make people’s lives better and I really like that we have such an impact on people’s lives,” Mackle told me.

“We have provided care for about 60,000 people. We provide 5,000 beds every single night for people in housing crisis.

“Yes, it is about innovation and looking for the next idea. Yes, it is about having the right people. But underneath all of it, it is about values.”

“I’d like to be known as a good boss, parent, wife and friend”: Emma Maye on being an unexpected CEO

Emma Maye is the chief executive of homebuilder Ardale, which she co-founded in 2012 with her husband and business partner Alan Hegarty. She also leads Core, a chain of six builders providers acros Ireland.

Ane yet, as she told Tom, Maye wasn’t always sure she wanted to go into construction. Her father, Liam Maye, had been a major figure in the industry. He’s a founding director of housebuilder Castlethorn and a partner in the development of some of Ireland’s biggest mixed-use and commercial projects such as the Dundrum Shopping Centre and the new town of Adamstown in west Dublin.

However, her father died unexpectedly in May 2008 at only the age of 64. This changed Emma Maye’s world, and she dedided tostep onto the breach.

“It was a big decision. We had a regular income coming in but I saw what I had to do for my family. It was my mother’s and father’s legacy. It was an incredible decision, but I decided to give it a go. I never looked back.”

The Drennan interview: “You just need to be patient and one thing we’ve lots of is patience”

In July 2007, before the Irish banking system, and the wider Irish economy, collapsed under its own hubris, Sean FitzPatrick, then a doyen of the Irish business community, launched a very public tirade against what he called ‘‘corporate McCarthyism’’. Within a short number of years, FitzPatrick would face multiple investigations by the state’s corporate enforcer, then led by Paul Appleby. But his 2007 comments were in keeping with the mood of the time.

When I caught up with Ian Drennan, chief executive of the newly-minted CEA, for an in-depth interview, I was keen to get his view of the shifts in Irish corporate culture since he replaced Appleby in 2012.

“I’m old enough to remember tax amnesties, we had a particular approach to paying tax or not paying tax in this jurisdiction,” he said.

“I had a role many years ago in the Dirt inquiry for similar sort of cultural issues. Have we moved on from then? I think it’s probably fair to say yes and I would think fair to say that we’re a much more compliant culture and society, and society is much more respectful of the rule of law and why that’s important. I think that’s reflected in boardrooms for the most part.

“Are there issues in boardrooms? Yes, of course, there are. I mean boardrooms are a function of people and people are imperfect creatures, as you know. So, we’re not naïve either.”

Under Drennan, the CEA has been busy. In the 18-month period between July 2022 and December 2023, it secured 107 court orders and five search warrants, took 213 witness statements, and effected 12 arrests. It also submitted 12 files to the Director of Public Prosecutions.

However, Drennan is not motivated by those numbers. Far from it. The way the corporate enforcer sees it, he could bulk them up dramatically by hounding small businesses for low-level misdeeds and misdemeanours.

But he has no interest in doing that. Instead, he promotes a compliance and regulatory culture of “proportionality”, “dissuasive enforcement” and engaging with businesses “behind the scenes”.

Staying power: How dealmaker turned leader Stephen Keogh plans to deliver for William Fry

If anyone should know the ingredients of success, it is Stephen Keogh. Head of corporate at William Fry for the past four years, he is an M&A heavyweight. Recent deals he has advised on include Starwood Capital acquiring a 50 per cent stake in Echelon Data Centres for circa $850 million (€778 million) and the Acrotec Group buying out Irish medtech Dawnlough.

Keogh is ranked the best M&A lawyer in Dublin by Chambers Global 2024. When Francesca sat down with him in August, he was three months away from taking over as managing partner of the firm, having won the race to succeed Owen O’Sullivan.

While he had some trepidation entering the leadership contest, he believes the internal election process was a healthy thing that will energise the partnership, telling Francesca: “People actually voted for you. They had an alternative, and they made a positive choice, as opposed to it just evolving around them.”

Over the course of the interview, he discussed prioritising work that has value for the firm as a growth strategy, he factors affecting M&A activity in 2024, and the risks of promoting a key corporate lead to a managing partner.

Within months, The Currency would report that William Fry was in talks with the Irish unit of Eversheds about a potential merger into William Fry.

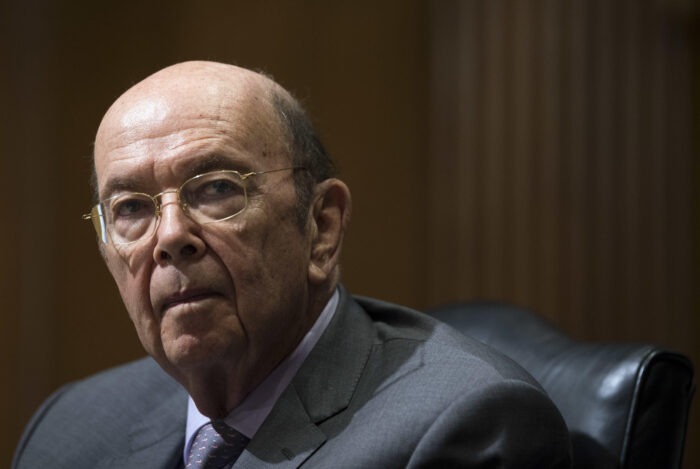

The King and I: Wilbur Ross on Trump, Putin, and saving Bank of Ireland

Wilbur Ross, a Wall Street titan who made his billions rehabbing distressed assets, was part of a consortium that helped keep Bank of Ireland out of state control when the Irish economy collapsed. In early 2017, he was ratified as Donald Trump’s commerce secretary.

Unlike many of his initial appointments, Ross has remained close to Trump, recently supporting the former president in his successful bid to reclaim the White House. He witnessed, firsthand, how Trump operates, telling Tom in an in-depth interview that it was crucial to separate his inflammatory rhetoric from the reality of his actions.

“Trump speaks in what I would call metaphor, not literally but figuratively,” Ross said. “He likes to make his message simple and bold, and so some of the extreme statements that he made he never fulfilled. It will probably be the same this time.”

When Tom asked if Ireland should be concerned that Trump will target its economy by trying to get US multinationals to pay more tax back home, he replied: “I think we are in a world where not just the US, but countries in general, are looking for new sources of revenue. But I also think that at this stage, so much American investment has gone into Ireland that the real question is, would it be uprooted just by taxes?”

Ross said Ireland had a highly skilled workforce that would be difficult to replace in the US: “The pharmaceutical industry, for example, is very well embedded in Ireland. They are making real products in Ireland, and are not just diverting the taxability of their royalties.”

“People in middle Ireland slip outside the social protection net, but are struggling”

The portfolio of the minister for finance is rarely rotated by choice. Stability and consistency are paramount. The occupiers of the office have traditionally been big political beasts.

In June, that role was bestowed upon Jack Chambers, a 33-year-old second-term TD who, while sitting at cabinet for several years, has never held a full cabinet portfolio.

Well-regarded by those who have worked with him, the elevation of Chambers represents a massive political play by his party leader Micheál Martin, and came just weeks after he was appointed deputy leader of Fianna Fáil. It represents a generational shift for Fianna Fáil, and perhaps a future-proofing of the party’s leadership.

In the aftermath of the budget, we sat down with Chambers to discuss his ideology, his views on the fiscal policy, and his insights into Budget 2025.

He rejected suggestions that it was a traditional election budget, pointing to the fact that it remained within the parameters the Government outlined in the Summer Economic Statement from a tax and expenditure perspective.

I asked Chambers about his political philosophy and how it framed his approach to this budget.

The budget, he replied, was “focused on the future and the long term”, and also about “demonstrating that the centre of politics works, that it delivers and it builds and strengthens living standards for people”.

From an enterprise perspective, he says he wanted to show how the government could “unlock the future of Ireland’s economy when it comes to the digital and green economy, but also innovation”.

“It is about protecting the progress we’ve made and demonstrating to people that we can make a difference, give them hope and build an economy which corrects the gaps that have built up and infrastructure in particular.”

Deirdre Veldon sets out her vision for The Irish Times – and the plan to achieve it

Sitting in the corner office of the Irish Times building on Tara Street, by windows offering a sweeping view of the south side of the city to the Dublin Mountains, Deirdre Veldon was warm, friendly and careful as she told Alice about her vision for the Irish Times group. It was her first major interview since becoming group managing director, and she talked bout the group’s acquisition strategy, prioritising digital subscriptions and enticing readers to pay for content.

Veldon took over at a challenging time. Paul Mulvaney, who she replaced, had departed the job after only a year and the group was in financial difficulty. In 2022, it reported a pre-tax loss of €5 million. When Alice suggested it must have been a difficult time to take on the MD role, Veldon was circumspect, preferring to talk about the present.

“We’re happy with the improvements that have taken place over the course of this year,” she said. “The group returned to profitability last year with growth in revenues of five per cent.”

She looks to The New York Times for inspiration. “I hate using them as an example because their scale is so great but you know, why not aim high,” she said.

“Their digital subscription model is based on creating a valuable package, a valuable bundle, and that includes good digital products. But they’re kind of different, they’re puzzles, or they’re cooking, or there’s Wirecutter [a product review website] or The Athletic [the sports publication] so, I suppose, in a similar way, what we’re trying to do here is to be able to enhance our bundle.”

“We have to concentrate on what’s in our control”: IDA boss on navigating FDI in a tumultuous world

Michael Lohan, the chief executive of IDA Ireland, had just returned from a trip to the US to meet clients when he sat down with Jonathan.

The US is a regular destination for IDA chief executives to visit given the sheer volume of US firms investing in Ireland but on this occasion, there was a lot more on the agenda than normal.

There was the turbulent political environment for a start, not to mention the threat of Trump’s protectionist trade policies. Plus, there was also the latest technology that everyone is wrapping their heads around.

“There’s probably a commonality in terms of the engagement and discussions in the US over the last 12 or 18 months,” Lohan said.

“Obviously it’s been dominated by a few things. AI, number one, almost every sector, every conversation is speaking about the opportunity that is AI and what that means.”

Lohan told Jonathan that from the discussions he has with clients, virtually all are opposed to tariffs.

“They tend to actually, in some ways, be counterproductive for trade and for open trade and I think for innovation. Tariffs are a very blunt instrument, but actually their consequences can be pretty severe,” he said.

But it would be wrong to only focus on the US when talking about “blunt” approaches to trade.

The end of this year will mark the conclusion of the IDA’s current four-year programme and it will set its sights on new goals.

Lohan is cognisant of setting realistic expectations for winning deals and what the job numbers will be.

With 300,000 jobs currently in play, there is a ceiling on just how many jobs the IDA can reach this year or in four years.

“We are ahead of where we actually had planned for during this cycle period. I think we’ve been fortunate because we’ve been able to capture a lot of growth pre-Covid and indeed post-Covid we actually captured and retained growth and that’s what’s led us to our 300,000 employees,” he said.

“In a business as niche as mine, you don’t really want to spiral out of control overnight”

Beyoncé, Cher, Gaga… for the mononymous women of culture and style, there is one go-to glove-maker.

This year, singer Taylor Swift joined their ranks, becoming the latest high-profile celebrity to wear gloves by Irish designer Paula Rowan. Alice caught up with Rowan in the aftermath of Swift wearing her gloves on her tour.

Rowan won’t go into detail about her celebrity clients. In some cases, like with Taylor Swift, she has signed an NDA. In other cases, she knows her customers value discretion and says that a business like hers is built on relationships. “I think that’s part of the reason why they keep coming to me as well, because I don’t say anything until I’m told it’s okay to.”

She added: “Celebrity endorsements are about the long term,” she said. “It’s the fact that it’s reinforcing the name ‘Paula Rowan’ and the association with us.”

“Rome wasn’t built in a day,” she said. “I think a creative business is slower to take off, but when it does, that’s when you can reap the rewards.”

“We have security issues that we need to address, and clearly we’ve underspent on defence”

David O’Sullivan is a former secretary-general of the European Commission and has held a string of top roles, including chief operating officer of the European External Action Service, director-general for trade, and, most notably, EU ambassador to the United States between 2014 and 2019.

Now serving as the EU’s sanctions envoy, he sat down with Francesca to discuss stymying the Russian war machine, the return of Trump and Ireland’s place in a volatile global landscape.

He argued Ireland needs to increase its attention and spend on security. ”If you look at our geographical position, you look at the undersea cables, you look at the overflight by Russian aircraft, it’s clear that we do have security issues that we need to address,” he said.

Despite these mounting geopolitical risks, Ireland has yet to deliver on its long-promised national security strategy. “We’ve underspent on defence, and I think this is widely accepted,” O’Sullivan noted. “But this is a shared problem across the whole continent, and we’re all going to have to rethink a little bit our economic model in Europe. Ireland is not going to be exempt from that.”

Francesca asked how he sees the eventual unwinding of sanctions playing out, as speculation mounts about the possibility of a new round of peace negotiations.

“Sanctions relief will undoubtedly be a part of some future negotiation. But we’re only going to give up the sanctions in return for very concrete commitments and actions by Russia, including on the reconstruction of Ukraine.”

“I’m not at all sure that that’s in the thinking of Mr Putin at this point,” he added.

“We are so close”: Fergal Mullen on Ireland’s economic transformation, fixing housing, and his rise to top-tier investor

Mullen grew up on the same street as Padraig Harrington and played on the same football team as Paul McGinley – both of whom went on to captain European Ryder Cup teams. He also ran alongside the late Jim Stynes, who won the Brownlow Medal, the highest individual award offered in Aussie Rules.

While they went into sport, he went into business.

Sitting in the elegant offices of Highland Europe, the British-Swiss venture capital firm he co-founded, in Soho in central London , Michael noted that it feels as though he is quite some way from those early days in Ballyroan.

Now, his company invests in growth-stage businesses, writing checks starting at €10 million. The London and Geneva-based firm has around €2.8 billion in assets under management and has made prescient bets on the likes of WeTransfer, consumer tech business Nothing, travel booking site GetYourGuide, and recently-acquired Irish sustainability software business AMCS.

Mullen’s story is one that crosses continents, overlaps with Olympians, weaves through the highest reaches of sport and education, and benefits from moments of what he describes as “luck”.

“I like playing a number of roles. I don’t like staying in my lane”

Yvonne Burke is the chief financial officer of Glen Dimplex. Best known as a maker of consumer appliances, Glen Dimplex is about much more than that as it employs 8,000 people globally in areas like precision cooling, heating and ventilation, and electric fires, though it often flies under the radar at home.

Burke is also low-key, passionate and gritty. She laughed when Tom asked about her experience with the media. “I’ve never done anything before,” she said. “Apart from the school magazine, that’s about it.”

Over the next hour, she told her own fascinating story and gave insights into one of Ireland’s most significant companies. “I like playing a number of roles. I don’t like staying in my lane,” she said.

“If we hadn’t got migration, let’s be factually correct, our economy would collapse”

Peter Burke, the Westmeath Fine Gael TD, was seven weeks into his new role as minister for enterprise, trade and employment when he sat down with Thomas in May.

They got straight down to business, with Thomas asking about the criteria that led him to select a list of measures to alleviate SME costs earlier that month. He first referenceds the evidence base for his decisions, which came from an analysis of the cumulative impact of upcoming social measures ranging from planned increases in the minimum wage and PRSI rates to leave entitlements and pension auto-enrolment over the next two to three years.

“My key metric was, first of all, to try and continue support in terms of cash flow,” Burke said. This was the reason for the extended deadline to access the €5,000 Increased Cost of Business (ICOB) grant and its doubling for the retail and hospitality sectors – “because the pressure is most acute on those and in essence, about 60 per cent of minimum wage workers are contained in those sectors”.

Looking to the future, Burke also insisted on the new “SME test” forcing all departments to “think small first” before bringing forward any new legislation or regulation: “The individual department that is bringing forward change would have to detail in the memo what effect that will have on the SME sector, be it a monetary or regulatory impact.”