US President Donald Trump has announced a new 20 per cent tariff on imports from the European Union, including Ireland – but later signed an executive order appearing to exempt key Irish pharmaceutical exports.

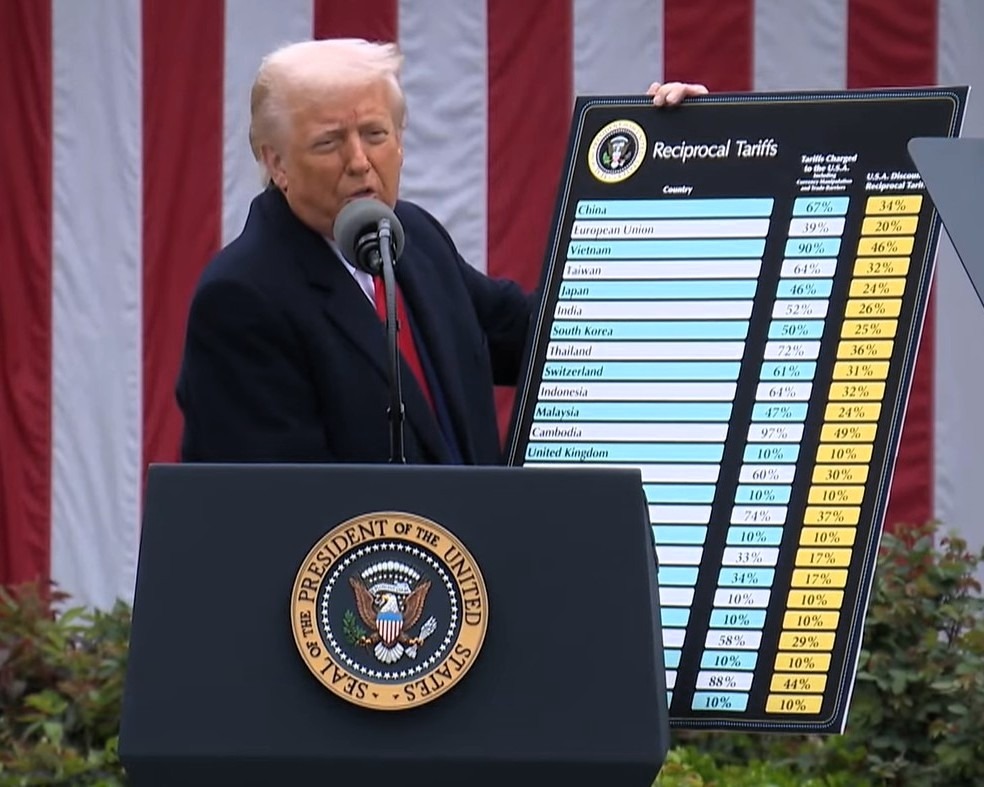

He argued that this was a “kind reciprocal tariff” because the cost of tariffs and other “non-monetary barriers” on US exports to the EU was estimated at 39 per cent on a chart handed to him by Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick. “We cut it in half,” he told a public event at the White House this Wednesday.

The list of new US tariffs ranges from a minimum of 10 per cent for a number of trading partners including the UK to a high of 49 per cent on imports from Cambodia. Trump did not initially provide details of how the tariffs would work, such as whether they would be temporary or permanent. He then signed executive orders.

One order later published on the White House’s website imposes a baseline US tariff of 10 per cent from April 5 and “reciprocal” tariffs, including that of 20 per cent on imports from the EU, from April 9. It also introduces exemptions including products already targeted by higher Trump tariffs, such as aluminium, steel, and cars, as well as “other products enumerated in Annex II to this order, including copper, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, lumber articles, certain critical minerals, and energy and energy products”.

Annex II was not included in the published executive order at the time of writing and details of the pharmaceutical exemption were not yet available.

According to a White House explantory document, “these tariffs will remain in effect until such a time as President Trump determines that the threat posed by the trade deficit and underlying nonreciprocal treatment is satisfied, resolved, or mitigated”.

*****

On the day he took office, January 21, Trump announced his “America first trade policy” and set April 2 as the date to roll out “massive amounts” of corresponding “tariffs, duties, and revenues”.

In the intervening time, governments and businesses have been trying to brace for impact – with strikingly little information to prepare for what is widely expected to affect global trade significantly.

As recently as Tuesday afternoon, Minister for Finance and Eurogroup President Paschal Donohoe told reporters: “It’s difficult to exactly identify what could be the scenario we’re facing into after tomorrow because we don’t yet know what the level of tariffs will be and we don’t yet know, if they’re announced, which ones will be permanent, and further measures could follow afterwards.

“All that, in truth, I can say at the moment… is on the basis of what President Trump has already said, I do believe it is very likely that we will experience an economic challenge in the next number of years, but on the basis of what I currently know, I believe it’s most likely that it will lead to a lower level of economic growth, with a risk in relation to how many new jobs could be created or some lost, and that will happen over the next two to four years.”

In recent weeks, The Currency’s reporters and contributors have explored the ramifications of expected blanket tariffs targeting the EU, and therefore Ireland. While published before Trump’s “Liberation day” announcement, they offer avenues to take a step back and prepare for the turbulent period ahead.

As early as February 15, writing from the US, Siobhán noted the disconnect between business and political circles. “American business owners are reportedly on tenterhooks, frantically consulting with lawyers and managers, every day trying to decide whether to make big and costly moves now, according to what is said to be coming, or later, with the relative security of a clearer picture,” she wrote.

“Little such exasperation is to be detected in the White House right now. The new federal appetite for tariffs is both lively and stubborn,” she added.

Among her colleagues, one journalist summed up the mood at an editorial meeting: “Just remember, it ends in ‘ffs.’”

More recently, Dan demonstrated how the common narrative depicting Europe as a “deindustrialising, open-air museum with an undynamic, welfare-dependent population” trailing behind an American economy that was “powering ahead on every front” was, in fact, incorrect.

When it comes to manufacturing – the very sector where trade imbalances have attracted Trump’s irate tariffs – Europe is doing much better than the US.

“The European economy is stronger than the current consensus view would have it – in my view it is remarkable that the EU is not in deep recession given the shocks of the 2020s,” Dan wrote. “This gives reason to hope that it can withstand the transatlantic trade conflagration to come.”

In another column last month, he examined Ireland’s diplomatic options as this divide deepens – not only on trade, but also on security and defence. Given Trump’s alignment with Russia on Ukraine, Ireland opting out of European defence integration would leave the country, Dan argued: “Just as we chose Europe over the UK during Brexit, we have no real choice but to choose Europe now over Trump’s America.”

When Taoiseach Micheál Martin visited Trump in the Oval Office ahead of St Patrick’s Day, the US president singled out American pharmaceutical multinationals locating manufacturing in Ireland, in part for export back to the US.

This is illustrated in the 22 per cent rise in pharma shipments by IAG Cargo out of Ireland in the past year, Jonathan reported.

Those firms have long used intangible assets and transfer pricing to shift profits to Ireland. On Tuesday, I explored whether the same moves could work in reverse to reduce exposure to tariffs. Several economists suggested that this could go as far as repatriating intellectual property rights, currently based in Ireland and generating large taxable profits in this country.

“This would radically lower reported imports; the import price is the price paid by the US headquarters to its subsidiary in Ireland or Singapore without changing real imports. And it would mean that the companies would have to pay tax in the US,” wrote American economist Brad Setser.

Not so sure, countered Kevin Norton, head of Deloitte’s transfer pricing team in Ireland. “Moving IP wouldn’t necessarily assist you in trying to manage potential tariff issues.”

However, both Norton and Carol Lynch, BDO’s partner and head of customs, said pharma multinationals might “unbundle” the price of products they ship to the US, breaking it down into the constituent parts of tariffable physical products and associated services or related costs. In any case, this would not be an easy task, they warned.

IDA Ireland chair Feargal O’Rourke, meanwhile, remarked that multinationals tempted to move intangible assets currently located in Ireland may face an exit tax.

Peter explored the ripples across foreign exchange markets as the reality of upcoming tariffs was gradually priced in and the fiscal stances of both the US and the EU took new directions.

This, he wrote, points to further appreciation of the euro against the US dollar in the near future. The same applies to gold, he wrote a few days later – a prediction so far confirmed by events.

“Friend-shoring”

Taking a wider view, what does the impending trade war mean for US, European and Irish positions in the global economy?

In an interview with Jonathan, Glenn Tiffert, a research fellow with the Republican-leaning Hoover Institution, discussed what he calls “research security” – the science and technology applications of national interest, such as semiconductors or defence-related tech.

Tiffert was visiting Ireland as part of an effort to keep bridges open across the Atlantic. “We are each other’s closest friends and allies, and we get so much from one another. A strong Europe needs a strong North America and vice versa,” he said.

When it comes to competition with China, western co-ordination must continue to achieve goals such as the “friend-shoring” of supply chains, he warned.

The implications of Trump’s new tariffs for the allocation of corporation tax between Ireland and the US are profound. The French economist Gabriel Zucman was in Dublin last week and I asked him in an interview whether his decade-long research identifying Ireland as a tax haven used by US multinationals was close to Trump’s own approach.

“I cannot stress how different his analysis of the situation is from mine because Trump, fundamentally – his view is that he wants to get rid of income taxation,” Zucman said. “He’s very much in favour of more international tax competition to the extent that it leads to the eventual disappearance of the corporate tax and eventually of all forms of income taxation. So in that sense, he, in fact, represents a continuation and an acceleration of the low-tax policies of Reagan or people like Thatcher in the 1980s.

“Now, there is one novelty, which is that he’s a great fan of tariffs. Essentially, his plan to repatriate more profit in the US is to become, first of all, an even bigger tax haven than Ireland or than any other country.”

Domestic Irish companies, too, are set to suffer from tariffs if they export to the US – especially in the food and drink industry.

Glanbia warned of “persistent and negative impacts” on input prices from tariffs and other geopolitical factors, triggering a spectacular share fall, as Ian reported.

By contrast, Kerry Group’s chief executive Edmond Scanlon seemed unfazed. In an interview, he told me tariffs on ingredients imported into the US, such as spices, would be passed on to customers. “It’s not that we’re immune. It’s more that based on what we know today – and let’s see what tomorrow brings – we feel we’re pretty well positioned. We already source, I think, about €1.5 billion of raw materials in North America itself,” Scanlon said.