Over the past year, The Currency has delivered an extraordinary range of investigative reporting, long-form features, and corporate analysis, shining a light on Ireland’s most consequential economic, social, and legal stories. From the rise and fall of local newspapers to the intricate dealings of billionaires and hedge funds, this collection captures the ambition, risk, and complexity shaping modern Ireland.

Alan English’s three-part series on Ireland’s local newspaper industry was a masterclass in long-form journalism. Drawing on 25 interviews, he chronicled the Celtic Tiger-era boom, the ensuing bust, and the financial reckoning that left unlikely millionaires in ruin.

Land ownership, legacy, and rivalry formed another recurring theme. Niall’s forensic mapping of the Magnier bloodstock empire in Tipperary exposed nearly 11,000 acres under the family’s control, while his two-part exploration of Maurice Regan’s land acquisitions highlighted the strategic and often personal battles shaping Ireland’s agribusiness landscape.

Alongside these features, investigations by Thomas investigations into Dublin landlords and Niall into Coldec’s emergency accommodation empire revealed the scale, opacity, and human impact of private interests in public services, driving transparency and accountability.

Corporate and financial affairs also dominated the year. From Dalata’s €1.4 billion hotel sale to Arena Capital Partners’ €112 million loan-note collapse, from Cerberus’s decade-long gains on Irish debt to Ardagh’s bond-for-equity restructuring, the reporting combined deep financial analysis with sharp storytelling. There were profiles of leading figures such as Conor Hillery at JP Morgan and the Barchester investors.

Other stories examined legal, technological, and international dimensions of Ireland’s economy. These ranged from Zagg’s punitive non-compete dispute and Airbnb’s legal exposure over Israeli settlements to high-profile HR and corporate espionage cases, as well as Ireland’s ambitions in semiconductors and green hydrogen exports.

We have published hundreds of stories over the past year. This is a mere sample, but I I hope tells the story of 2025.

*****

Breaking News: The rise and fall of Ireland’s local newspaper industry

Alan English joined The Currency this year after a distinguished career in newspapers, including five years as editor of the Sunday Independent. We were both delighted and humbled to welcome a journalist of his calibre — and his first major contribution more than lived up to that reputation.

In fact, it wasn’t just one piece, but three masterfully interwoven articles. Across these long-form features, drawing on 25 interviews, he chronicled the rise and fall of the local newspaper in Ireland. It was a monumental undertaking and quickly became one of the standout works of the year.

Part one told the story of Celtic Tiger-era frenzied auctions for regional titles and how it made millionaires out of many, while putting most of the buyers on the way to bankruptcy.

In part two, he explained how big hitters like Dómhnal Slattery were convinced there was serious money to be made in Ireland’s local newspaper business. But, as Alan put it, as ambitious new players emerged and legacy owners wrestled with huge offers, a brutal financial reckoning lay ahead.

In part three, he looked at the outcome and conducted a fascinating interview with the newspaper magnate Malcolm Denmark.

It was a fascinating series that showcased long-form journalism at its best.

As Alan put it: It’s about a boom and a bust – it’s also about a bubble, of which there is much nervous talk these days in the financial markets. It’s the inside story of the crazy years when Ireland’s local newspapers were being sold for stratospheric money, making unlikely millionaires out of many – and putting most of the buyers on the road to ruin.

The Magnier map: How much land does the bloodstock dynasty really own in Tipp?

In a media first, Niall went through painstaking work to map out the true scale of the Magnier bloodstock dynasty’s holdings in Co Tipperary. After a forensic analysis of dozens of land folios and planning files, Niall was able to confirm that the family is sitting on a staggering holding of close to 11,000 acres in Co Tipperary.

This figure is the result of connecting the dots across land owned between Fethard, Ballydoyle, and Clonmel in the fertile Golden Vale part of the county.

Niall’s deep dive also revealed a massive generational handover of land. The bulk of that land—nearly 6,000 acres — is now registered to the “Coolmore kids,” JP Magnier and Katherine Wachman, while another 3,000 acres is held by corporate entities. This land is vital for their 2,000-horse operation, requiring enormous space for biosecurity and huge volumes of fodder.

The ultimate takeaway is that a powerful family is quietly consolidating its legacy in the Premier County. If Castlehyde Stud and the fertile lands of the Blackwater Valley in East Cork were the forging of John Magnier and his Coolmore empire, then the amassed land in the Golden Vale in south Tipperary has cemented the legacy of the 77-year-old billionaire’s bloodstock empire.

The Regan register: How the battle for Tipperary farmland “became personal”

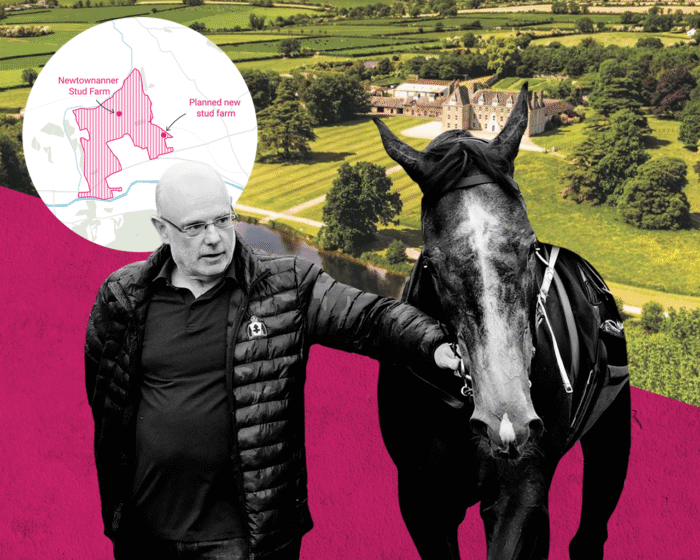

Niall also explored the emerging rivalry between Magnier and the Irish-born, US-based construction titan Maurice Regan over land in Co Tipperary, which culminated in their battle over the Barne Estate.

Amid the legal battle over Barne (covered forensically by Francesca throughout the year), Niall dove into the land and corporate holdings of Regan in Ireland across a two-part series. First, he looked to Tipperary, piecing together a 1,000-acre landbank in the south of the county centred around his bloodstock business, Newtown Anner Stud.

Company filings examined for the series show Regan has pumped €49 million into the jewel-in-the-crown stud in recent years with the pursuit of more acreage — notably the contested 751-acre Barne Estate — a strategic move to ensure the long-term viability of the bloodstock operation.

In the second part of the series, Niall examined Regan’s more corporate side, moving from the fertile plains of south Tipperary to his interests in bars and restaurants in the capital through his stake in the Mercantile Group.

With a further multi-million euro investments in biomass energy and a burgeoning lending vehicle, including acquiring Gerry Gannon’s Nama debts, Niall explored how Regan has now firmly planted himself in the top echelon of Ireland’s business elite.

Blown off course: How Arena Capital Partners’ €112m loan-note crisis unfolded

In early December, Arena Capital Partners, a renewable energy company, was placed into liquidation following an unsuccessful examinership bid.

Mr Justice Oisín Quinn made an order appointing Shane McCarthy of KPMG as liquidator after the insolvency practitioner told the court there was “no longer any reasonable prospect of survival” for the company.

So just what happened?

Arena Capital Partners was set up in 2014 by Ian Greer and Barry Corcoran to get in on the renewable energy boom, mostly small- to mid-scale wind farms. They weren’t going the traditional bank route for funding — they raised money through unregulated loan notes, offering investors really high interest rates, up to 10 per cent annually. At its peak, the company had over 100 wind turbines, plus stakes in maintenance companies and even a social housing business.

The trouble is, all of this expansion was funded by those unregulated loans. When confidence in the market dropped around 2023–2024 — partly due to other high-profile loan collapses and economic uncertainty — Arena couldn’t raise more money, and it couldn’t refinance the debts coming due. Suddenly, it owed investors €112 million, and cash was running out.

Tom had the inside story.

A capital conundrum: Why Dalata is exploring a sale – and how much the hotel operator could fetch

During the dark days of the global financial crisis, the hotelier Pat McCann saw something few others could: opportunity.

His industry was in crisis, so woeful that even Nama, the agency established by the State to offload toxic assets, had not put most of its hotels on the market for fear no one would buy them.

Yet, McCann and a small team built and grew Dalata into a stock market-listed entity that was the largest hotel player in the country, and with a footprint further afield.

In March, it was put up for sale. That day, I wrote about the potential purchasers and the potential price tag, while days later, I wrote that the sale of the business would be a potential litmus test for the wider Irish economy. Later, I spoke to its CEO, Dermot Crowley, about the sales process and what to expect in the future.

In the end, a Scandinavian consortium that had been circling Dalata reached an agreement to buy the business for €1.4 billion. It was less than many expected, but it was the price someone was willing to pay. It was one of the corporate stories of the year.

For sale: The revival of iconic Battersea, once in Irish hands, is a case of what might have been

Battersea Power Station has long held iconic significance in the London skyline. The building’s famed chimneys provided the backdrop for a Pink Floyd album cover and powered landmarks like Buckingham Palace and the Houses of Parliament, but had been decommissioned since 1983, gradually falling into a state of dereliction.

That was until its resurrection in recent years, when it opened its doors as a spectacular mixed-use development home to Apple’s UK HQ, high-end apartments, and an array of retail units.

In a wide-ranging feature, Michael charted the history of the power station as the commercial portion of the redevelopment came up for sale. He spoke to those responsible for making use of the last chance Battersea had to survive. The developers, architects, and engineers spoke of an incredibly complex project and the need for a strong relationship with state entities to ever pull something like it off.

The piece also charts Battersea’s stint in Irish ownership, when developers Johnny Ronan and Richard Barrett acquired the 16-hectare south-west London site before the financial crash.

Battersea stands as a case of what might have been, but nonetheless, there are plenty of lessons to learn here for governments and developers alike when it comes to tackling a project of such scale.

Revealed: The 23 Dublin landlords paid millions for homeless accommodation

Following a one-thousand-day freedom of information battle with Dublin City Council, Thomas obtained details of the payments made to commercial landlords contracted by the Dublin Region Homeless Executive (DRHE), a unit of the local authority, to provide accommodation for homeless people across Co Dublin.

Those payments totalled €140 million in 2023 and have kept rising as the State increasingly relies on private property to secure temporary shelter for the victims of the housing crisis. The public procurement of this service, however, had remained opaque until then.

With help from Niall, Thomas analysed the data and identified the ultimate landlords behind hundreds of companies including established players, such as the McEnaney family already well known for its business with the separate Ipas scheme housing asylum seekers, as well as previously unknown businesses such as the Forbairt Group receiving €10 million in annual payments from the DRHE.

Since the publication of this article, Dublin City Council has included DRHE payments to landlords in the quarterly publication of its purchase orders, in line with general procurement transparency rules.

The barber, the painter, and the investors behind the Coldec emergency housing empire

As he did last year, Niall drilled down into the Coldec Group again, but this time for its role in providing homeless accommodation services. This network of companies — already a powerhouse in housing asylum seekers and Ukrainian nationals, bagging over €57 million since 2022 — is now confirmed as one of the top players in the domestic homeless industry.

Following Thomas’ epic FOI battle to finally get Dublin City Council to release details on payments to private emergency accommodation providers, Niall crunched the numbers, identifying a range of Coldec companies which, combined, hoovered up over €16 million from the Dublin Region Homeless Executive in 2022 and 2023 alone.

The whole operation, built on a property portfolio valued north of €70 million, is clearly a serious player in this space, but, as Niall also explored, has undergone a recent corporate shake-up.

Digging into company filings, Niall showed how a key figurehead for the group resigned from more than two dozen companies in rapid succession, coinciding with the arrival of a debt advisory heavyweight. Is this a new chapter for one of the State’s most significant private emergency accommodation landlords? Niall may well let us know in 2026.

Trade secrets and non-competes: Inside Zagg’s failed legal pursuit of an Irish employee

One of the stories that stayed with me this year was the long-running legal battle between US mobile accessories group Zagg and a former Irish executive, not because it involved blockbuster financial numbers or a corporate collapse, but because it revealed how damaging employment disputes can become when litigation turns punitive.

On the surface, this was a fairly standard post-departure dispute: A senior employee leaves, a non-compete is invoked, and questions arise over company data. But as the case dragged on for nearly 18 months, it evolved into something far more instructive. Zagg’s legal pursuit of Dermot Keogh ultimately failed in court yet, along the way, it cost him two subsequent jobs after potential employers opted to cut ties rather than risk being drawn into litigation.

What made this case worth following was the imbalance between outcome and impact. The Delaware court found no breach of the non-compete, no misuse of trade secrets and no evidence of competitive harm. The judge also questioned why the company continued to pursue claims it made little effort to prove. Still, the process itself proved punishing: months out of work, mounting legal costs and significant personal strain.

For readers, the story also resonated because of Zagg’s significant presence in Shannon and the increasing crossover between US employment law and Irish-based operations. It was a reminder that restrictive covenants, often signed as routine paperwork, can have far-reaching consequences when aggressively enforced.

Irish “James Bond” tells court he was “encouraged” to make “false” Russian money claims to the Central Bank

In March, an unusual application was made to the High Court. A US multi-billion-dollar HR company, Rippling, asked the court for a preservation order to be served on Keith O’Brien.

The North Dublin global payroll manager was working at Rippling’s Dublin offices. But his employer suspected him of corporate espionage on behalf of its US rival, Deel. It set a honey-pot trap, and gathered enough evidence to go to the court.

At first, the Irish “James Bond” refused to cooperate. He appeared without legal representation in the High Court to say he had destroyed the phone he’d been ordered to preserve; it later emerged that he “smashed [it] with an axe and put it down the drain in [his] mother-in-law’s house”.

O’Brien then got himself a lawyer and changed tack. He provided as much data as he still had to the court and then entered a cooperation agreement with Rippling.

In an explosive affidavit in April, he alleged that he’d been paid in cryptocurrency to spy on his employer directly at the request of the Deel CEO Alex Bouaziz, who made reference to James Bond. He said he’d also been instructed to make false allegations against Rippling to the Central Bank.

The case is still playing out in Ireland and in the US. Deel denies all allegations of wrongdoing.

Tom, Alice and Francesca have covered the case extensively throughout the year.

H2 where? A reckoning with Ireland’s green hydrogen potential

When Europe suddenly realised its addiction to Russian gas in the wake of the full invasion of Ukraine, no country was more exposed than Germany. After the Nord Stream pipeline blew up in the Baltic Sea, Berlin scrambled to find international partners willing to supply the German economy with a green alternative – hydrogen gas made with renewable energy.

Over the summer and autumn, Thomas investigated Ireland’s response to this unexpected demand, which appeared to dovetail with this country’s offshore wind potential extending way beyond domestic needs.

Through freedom of information requests and diplomatic and industry interviews, part one of this article chronicled strong Irish-German engagement on green hydrogen exports at first, helped by political alignment between the Green ministers in charge of energy in both countries at the time. The UK, too, was in the loop as a potential transit country for trans-European pipelines.

Soon, however, efforts waned at the official level, until elections reshuffled the political cards. In part two, Thomas explored further how green hydrogen exports in general may contribute to the decarbonisation of Ireland’s energy system. High costs and engineering constraints, such as the unsuitability of hydrogen plants to absorb short-duration bursts of excess renewable energy, have emerged as serious challenges for this burgeoning industry.

Yet at the regional level, projects are getting off the ground. They will form a test bed to solve those problems and potentially turn this new green gas into a significant link in Ireland and Europe’s future energy chain.

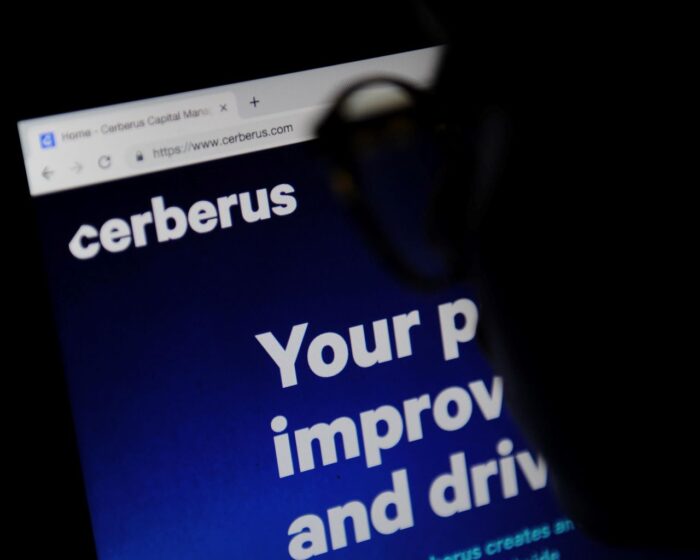

10 years a vulture: How Cerberus has done out of a decade’s worth of Irish loans

Since our establishment, The Currency has sought to shine a light on the global hedge funds that acquired so much of Ireland in the aftermath of the financial crash. Earlier this year, Thomas looked over three parts at the role played by Cerberus: the money it made, the deals it conducted, and the debt it acquired.

It was a remarkable study. As detailed in part one of his series, every single acquisition of Irish bad loans by Cerberus during the early post-crisis period of fire sales studied by the Bank of International Settlements has now returned a profit to the US vulture fund.

In a further article, Thomas worked out the total cash returns to date from Cerberus subsidiaries pursuing Irish borrowers for repayments at nearly €1 billion. There will be more, as the firm continued to buy up Irish NPL portfolios until the end of 2023. It is also worth noting that Cerberus itself borrowed to leverage those deals and paid interest to global banks, led by Deutsche Bank and Bawag, generating comparable gains for them.

“These sums are the price that the Irish financial system, comprising private and State-owned institutions, agreed to pay Cerberus to get rid of a pool of bad debt written down to a value of €10 billion,” he wrote.

Damages of €823,500: Denis O’Brien loses defamation suit over “Sinn Féin/IRA” slur

“Human rights lawyer Darragh Mackin didn’t look up from his laptop as the jury returned to court just after 1.30pm. The nine men and three women had been deliberating for around two and a half hours and the verdicts were in.”

So began Francesca’s long read on a lengthy defamation by two Belfast human rights lawyers against the businessman Denis O’Brien and his public-relations spokesman James Morrissey.

In the end, a jury awarded substantial and aggravated damages to Mackin and his colleague Gavin Booth, defamed by a press release issued on behalf of O’Brien in response to a 2016 report that criticised his then-dominant position in the media market. (The award sum has since been appealed.)

As Francesca put it, it was a battle of attrition.

“Over the course of the eight-day hearing, limbs of the defence fell away — like the denials that Mackin and Booth were co-authors of the report, or that they were identified as such.

“Witnesses, too, did not materialise. Lynn Boylan was flagged early on as a likely witness for the plaintiffs, but was never called to give evidence. O’Brien regularly attended court 25 but opted not to testify.

“In total, the jury heard from five witnesses, four for the plaintiffs: Mackin; Booth; and journalists Mark Tighe and Tom Lyons, who separately contacted the Belfast-based solicitors on reading the O’Brien press release following its release on October 26, 2016. The only defence witness was Morrissey.”

“The ‘teen’ category was one of the most profitable”

One of the most troubling and consequential stories I followed this year involves Pornhub, now operating under its parent company Aylo, and the complex web of lawsuits over child sexual abuse material on its platforms. It’s not an easy story to read, but it’s one that highlights the intersection of technology, corporate structure, and accountability — and why business leaders need to understand the broader social consequences of digital platforms.

The story begins with Jane Doe #1, whose abuse was filmed and uploaded without her knowledge. Along with Jane Doe #2, she has pursued a class action against Pornhub’s parent companies, claiming the platforms knowingly profited from videos of minors. The US lawsuit, filed in Alabama in 2021, has since expanded to cover anyone under 18 appearing in content uploaded since 2011. The damages sought could exceed €1 billion, illustrating both the scale of the alleged abuse and the financial stakes for companies operating global digital platforms.

What makes the case particularly interesting from a business perspective is the corporate structure behind Pornhub: subsidiaries in Ireland, Cyprus, Luxembourg, and the US, all connected through a complex chain of ownership. The Irish case supports the US proceedings, seeking to preserve evidence and ensure assets cannot be hidden.

I chose this story because it underscores a critical lesson for businesses: Digital growth and profitability cannot come at the expense of ethical responsibility.

Inside Ireland’s bid for the world’s biggest chipmakers

Ireland’s ambition to become a European semiconductor powerhouse has quietly become one of the country’s most high-stakes economic gambles. At the heart of the National Semiconductor Strategy, launched by Minister for Enterprise Peter Burke, is a potential €30 billion fab in Oranmore, Co Galway — a prize often described by insiders as “landing a whale.”

The story is fascinating because it sits at the intersection of politics, diplomacy, and global tech. The Government’s approach has been methodical: slow release of information, careful site selection, and engagement with multinationals like TSMC and Nvidia. But questions abound over feasibility, infrastructure, and whether €3.2 billion of state investment in utilities, land, and roads is the most effective way to foster long-term growth in Ireland’s semiconductor ecosystem.

Speaking to John, experts highlight that fabs are capital-intensive, highly automated, and bring relatively few spillover benefits for local start-ups. They argue Ireland would gain more by focusing on high-value R&D, spin-outs, chip design, and chiplet packaging — areas where the country already excels, from UCD and UL to the Tyndall Institute in Cork. The recent EU Chips Act wins for Tyndall underline this potential, demonstrating that Ireland can compete globally in research and prototyping even without a €30 billion fab.

The story also underscores broader challenges: a lack of diplomatic engagement with Taiwan (home of TSMC), competition from other EU countries offering subsidies, and a small, ageing pool of engineers. The human factor — nurturing talent and retaining graduates — may ultimately matter more than the headline-grabbing fab.

The kids might be alright

In February, Michael explored the various ways governments have sought to protect children online in a two-part series. Australia has opted for the most eye-catching approach to date, imposing an outright ban on social media for those aged under 16.

The noise around online safety has ramped up in recent years, with parents looking to the authorities for help. That noise was undoubtedly amplified by the publication of Jonathan Haidt’s bestseller The Anxious Generation, which spoke of a growing epidemic of mental illness driven by the “great rewiring” of childhood.

In part one of The kids might be alright, Michael detailed the three routes governments can take to tackle the dangers of social media for children and highlighted the unintended consequences that can come with the Australian approach, including the potential movement of underage online activity to unregulated platforms.

In part two, the focus was on Britain and Europe’s more targeted regulatory approach, which has faced intense pressure and scrutiny from the Trump administration.

Ireland is contemplating a ban of its own on social media for underage users. The early results of Australia’s social experiment will be watched closely – expect this story to ramble on into the new year.

The next RTÉ? The litany of failings behind the Arts Council’s €6.5m IT debacle

The financial failings at the Arts Council were one of the big stories of the year. Niall covered it extensively over the period, drawing on files, records and documents. In this article, he reported on how a new arts department report gave a blow-by-blow account of what happened with its overly ambitious IT project, where the problems lay, and who may lose their job over the fiasco.

“So, what went wrong? What happens next? And whose head may be on the chopping block in the latest scandal to grace the department’s halls just as the dust was finally settling on the whole sorry RTÉ debacle?”

This article provided some of the answers.

Eversheds Sutherland is dead. Long live Eversheds Sutherland

In the autumn of 2024, the leadership of Eversheds Sutherland Ireland began quietly negotiating a merger with William Fry, hoping to create a legal powerhouse capable of challenging Ireland’s biggest firms. Gerard Ryan and Stephen Keogh, old friends from their trainee days, were at the heart of the idea, dreaming of bigger, more international deals.

At first, the plan seemed promising. Equity partners could transfer their stakes to the new firm, and there was a chance for growth and prestige.

But not everyone was on board. Pamela O’Neill, the head of dispute resolution, decided she wanted to stay with Eversheds Sutherland rather than join William Fry. She quickly gathered support from other key partners, creating a split within the Irish team.

Eversheds Sutherland International in London, caught off guard by the merger talks, tried to intervene and convince partners to stay, but the momentum was already shifting. Rumours leaked to the press in December.

Over the following months, more partners made decisions about their future. Some defected to William Fry, others remained loyal to Eversheds Sutherland International, and many were left in limbo. By May 2025, the merger had officially fallen through. Both firms announced they would remain independent, signalling the end of the ambitious plan.

Meanwhile, O’Neill and her team began rebuilding Eversheds Sutherland International in Ireland.

After €40m losses, Nutriband faces crucial approval phase as its CEO pitches for the Áras

Gareth Sheridan, the Irish-born, US-based businessman, decided to return home and run for the presidency this year. As it transpired, he did not make it on the ballot paper.

Part of the reason for that was the forensic reporting of his business affairs. And in this piece, Thomas painstakingly went through the actual numbers and strategy of his business, Nutribrand.

As Thomas put it: “As told by the hundreds of pages of US Securities and Exchange (SEC) filings released by Nutriband and nearly all signed by Sheridan over the past decade, this is the business story of Ireland’s newest presidential hopeful, the backers he has partnered with along the way – along with the questions raised by his decision, as he turns 36 later this month, to put the company aside as it enters its make-or-break FDA approval phase.”

15 years and €24m later, what have we learned about the failures in Irish Nationwide?

Some 15 years after the Central Bank began an investigation into Irish Nationwide’s commercial lending in Ireland, Belfast, and London between 2004 and 2008, and 10 years after the establishment of a statutory inquiry by the Central Bank to “independently inquire” into the building society and five people involved in its management, the regulator’s investigation concluded last year.

It did not come cheap, and it has not been easy. The society’s former finance director, John Stanley Purcell, and Michael Fingleton, its controversial CEO, brought court proceedings to stop the inquiry, including a challenge to the constitutionality of the legislation that gave the Central Bank the power to hold this, or any other, inquiry.

All told, the independent inquiry sat for 105 days over a five-year period. I reported on its findings and, in a follow-up column, explained why it told us what we already knew.

Inside the Barchester deal: How Irish billionaires tapped US appetite for UK care homes

In October, Dermot Desmond, John Magnier and JP McManus netted a huge windfall from the sale of their Barchester Healthcare business to the listed US group Welltower. How did it happen?

As Michael explained, in the early 1990s, Mike Parsons opened a care home in the Cotswolds after struggling to find quality care for his elderly relatives. Recognising the wider need for such facilities across the UK, he quickly sought investment to expand.

That’s where three Irish business magnates stepped in: Desmond, McManus, and Magnier. They backed Parsons’ venture, then called Planvigil, which was rebranded as Barchester Healthcare in 1995. Over the next three decades, their investment grew exponentially, transforming Barchester from a single farm-based care home into one of the UK’s largest operators, with over 200 care homes and 17,000 staff.

The company was sold for €6 billion this year. Michael had the story of the deal.

“The very best of the Irish in the City”: JP Morgan’s Conor Hillery has been a star in the making

Conor Hillery’s rise to the top of JP Morgan’s European operations is the kind of story that makes you sit up and take notice. Earlier this year, the Dubliner was named co-CEO of JP Morgan’s EMEA business, putting him at the helm of one of the most important financial institutions in the world. For those who’ve watched his career, the promotion comes as little surprise.

“Conor has been a real star of the younger Irish business community in London over the past 10 to 15 years,” said Vincent Keaveney, a former Lord Mayor of the City of London. “He’s clearly a really successful dealmaker… and very often seen on the big M&A transactions. So I’m not surprised that he’s rising through the ranks into senior management.”

Keaveney highlighted what many who know Hillery already suspected: his blend of integrity, charm, and intelligence.

After training as an accountant at KPMG in Dublin, he moved to Kleinwort Benson and then to Cazenove in 2002. Cazenove’s eventual acquisition by JP Morgan brought him into the heart of one of the world’s banking giants, and he steadily climbed the ladder, impressing colleagues along the way.

“Conor was one of those young guys who was clearly going to be a star from a young age, based on a combination of competence and intelligence, married with charm and an easy way with clients,” Robert Pickering, former CEO of Cazenove, recalled. “That has proved to be the case.”

As Michael noted in a profile of him, beyond banking, Hillery’s Irish roots remain central to his identity. Educated at Gonzaga College and University College Dublin, he comes from a family steeped in public service and finance. His father, Brian Hillery, was a politician, a banker, and Ireland’s first professor of industrial relations, while his mother, Miriam Davy, is the daughter of rugby star and Davy Stockbrokers founder Eugene Davy.

Where to next after months of talks over Ardagh’s “abandoned” bonds-for-equity deal?

This year, Ardagh’s senior unsecured bondholders, who were owed about $2.4 billion (€2.1 billion) by the Irish-led packaging company, swapped their bonds for a 92.5 per cent stake in the business.

Thomas has covered the corporate negotiations over the past year. In June, he told the full story of its $12.5 billion bond pile, explaining how it gave clues about the options left on the table. He later explained how the new owners are hoping to pay themselves handsomely – but they must turn the business around first.

The Dublin office and the Israeli settlements: How Airbnb’s Dublin entity became a legal flashpoint

From “stunning views” to a relaxing pool, Airbnb listings in Israeli settlements might look like dream getaways – but these homes are in settlements considered illegal under international law. Now, Airbnb Ireland could face serious legal scrutiny.

In August 2023, Palestinian solidarity group Sadaka and legal non-profit Glan filed a criminal complaint alleging Airbnb Ireland is complicit in war crimes by facilitating accommodation in these settlements. An Garda Síochána initially refused to investigate, but earlier this year, the High Court struck down that decision, meaning the case must be reconsidered.

The complaint draws on international and Irish law, including the Geneva Convention and the Rome Statute, which define land appropriation and transferring civilians into occupied territories as war crimes. Glan’s Gerry Liston said Airbnb Ireland is “aiding and abetting those war crimes” by listing properties in settlements.

Niall, who has assiduously covered business links with Israel for The Currency, had the story.

Tweets, relief, and “vindication”: High-stakes Web Summit feud settles

Set down for nine weeks at trial, in the end, the battle between the co-founders of the Web Summit was done and dusted in seven days, two of which were spent in intense settlement negotiations.

Justice Michael Twomey said he was pleased for the three individuals involved who had saved a huge amount in costs, time, and reputationally.

He thanked the lawyers for their hard work in achieving a resolution from what was an “entrenched position”. He then wished the three parties the best.

Paddy Cosgrave and Daire Hickey were in court for the brief hearing. David Kelly stayed away.

Afterwards, Cosgrave made a statement to the assembled media thanking his legal team and calling it a “great day for Web Summit”.

It is a story and a dispute that we have covered extensively in recent years. This was the day the dispute ended.