Last week I wrote about how Japan got stuck in a rut for 30 years. Individuals in Japan expected the economy to be dismal so they dialled down their spending and investing. The aggregate of these decisions made the economy dismal. And once the idea got embedded, it proved very hard to shift.

What Japan shows us is that economies don’t have a “level” on which they naturally converge. For the last 30 years, Japan could have grown at a steady happy pace – or it could have blown up from overheating and hyperinflation. In the event, it got stuck in a low-growth rut.

When you consider the difference between a healthy growing economy and a 30-year recession in terms of people’s lives and well-being, it boggles the mind. As the recently deceased economist Robert Lucas put it, “Once you start thinking about growth, it’s hard to think about anything else.”

Who benefits

The thing about it is, you don’t have to go to Japan to see squandered potential. Here in the eurozone the economy has been stuck in low gear since 2010. It’s been left behind by the US.

I’ll get into the weeds later. But the upshot is that ever since the end of the financial crisis, the US government has driven its economy harder than the ECB has.

The downside of the US’s strategy is that it has been at greater risk of inflation. And indeed in the last two years, the US has had self-inflicted high inflation.

But I’d argue it’s still been worth it. The benefits of running the economy hot are large.

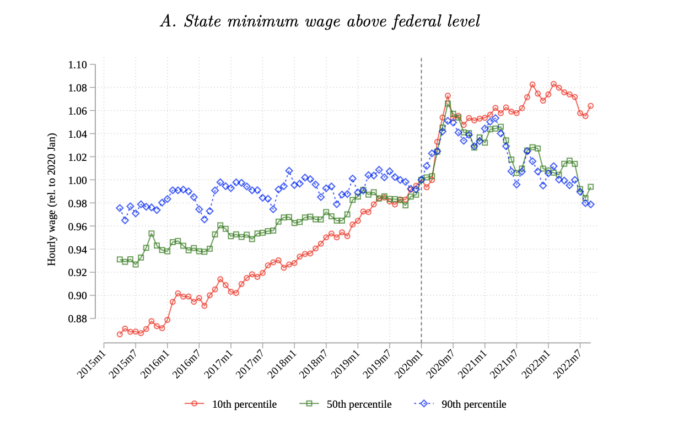

First and foremost, a hot economy is the best anti-poverty programme there is. When the economy is hot and there isn’t a reserve army of unemployed workers, wages at the bottom start to rise. Between 2019 and July 2022, workers in the bottom tenth of the US income distribution have seen the biggest wage gains. They are represented by the red line in the chart below, taken from this 2023 paper by Autor et al.

Part of this effect is driven by increases in minimum wages, but most of it is not. And indeed, governments feel more comfortable raising minimum wages in the context of a hot economy.

The last time the US economy was running red hot was in the late 1990s. The same thing happened back then. In The Benefits of Full Employment by Dean Baker and Jared Bernstein, the authors said of the full-employment Clinton years:

“The benefits of full employment are far-reaching. While many worthy social programs can improve on market outcomes, there is no better way to lift the living standards of all working families than through full employment in the labor market…

“Full employment in the 1990s helped to reverse the long-term decline of the real wages of many workers, particularly those at the lower end of the wage scale, as well as the stagnation in wages for higher-paid white-collar workers. Moreover, the seemingly inexorable increase in inequality slowed in the late 1990s, as the incomes of workers at the bottom grew more quickly than those of workers in the middle of the income scale…

“One way to characterize these is with respect to job quality. The tautness of the labor market meant that, in order to hire and retain even low-wage workers, more employers had to offer health and pension benefits than would have been the case had weaker demand for labor prevailed. Also, when the labor market tightened enough, the share of so-called involuntary part-timers, i.e., those employed part time but seeking full-time jobs, declined.”

A hot labour market benefits the poor by increasing wages and by tempting more people back to work. When jobs are plentiful and well-paid, marginal workers decide to enter the labour market. In the US the proportion of working-age people in jobs peaked in 2000. But now, with the labour market running hot, it’s at its highest level since 2007. The employment rate for women has never been higher. And the unemployment rate for black workers has never been lower.

Here in the eurozone the economy has never run hotter — and the proportion of working-age individuals in jobs has never been higher.

Appendix: what counts as hot?

When I assert that the economy is hot, what I’m referring to is nominal GDP growth. NGDP is the sum of all spending in the economy. It’s the number that tells you how aggressively the economy is being stimulated.

The reason I use NGDP growth rather than inflation is because inflation comes from the interaction between the demand side of the economy and the supply side. When Putin invades Ukraine and causes energy prices to spike, the resulting inflation isn’t a result of the economy being overstimulated. That’s coming from the supply side rather than the demand side.

Estimating the right level of NGDP growth is an inexact science. But for the eurozone, it’s probably somewhere around 3.5 to 4 per cent per year. Between 2010 and the start of the pandemic in 2020, the eurozone only managed an average of 2.5 per cent. I could be more forgiving to the ECB and start in 2014. But even since then, it has managed only 3 per cent NGDP growth.

Part of it was that monetary policy was too timid. But as the Japanese will tell you, it’s hard to break out of a low-growth rut. A lot of people need to be convinced to change their spending and investment plans. It’s especially hard for the ECB to shift the economy in a big way, since its governance is so divided.

The US would be expected to grow faster in part because it has more immigration. But that doesn’t explain the difference between the two economies. The US averaged NGDP growth of 4.0 per cent in the same period.

What’s done is done. But the point is that we’re now at a point where the eurozone economy is running hotter than ever. NGDP in the first quarter was 7.2 per cent bigger than a year earlier. That’s too hot, to be sure, and the ECB will need to cool it to the 3.5 to 4.0 per cent range.

But this is a golden opportunity for the eurozone to get out of its rut. The old idea, that people should spend and invest timidly, has been banished. If the ECB can stick the landing in the 3.5-4 per cent range, we could have a more prosperous eurozone. Particularly for the worst-off.