At the time of the last general election in 2020, the number of people in homeless accommodation in the State was 10,148. That election was dominated by the vexed issue of housing and homelessness, with the emotional swell attached to the crisis contributing to the massive gains made by Sinn Féin.

On Friday, as the country went to the polls for another general election, the Government published figures revealing that the number now stood at 14,966. Of those, some 4,645 were children under the age of 18. The number of those in homeless accommodation is, sadly, a new record.

Yet, despite the month-on-month, year-on-year increase in the number, the issue of homelessness played little part in this election campaign. Certainly, based on the initial exit poll and tallies during the first day of counting, it did not swing voters either way.

Housing and homelessness may have been listed as the number one consideration for 28 per cent of voters in the exit poll, but it seems many opted to cast their vote based on the more base impulses of economic prosperity and financial well-being.

Some 52 per cent of those surveyed in the exit poll believed that the standard of their lives had stayed the same over the past 12 months, while 13 per cent believed their lot had improved. That meant 35 per cent of the voters felt things had got worse.

We can safely assume they did not vote for the governing parties. But plenty of other voters did.

Sinn Féin is poised to make gains, but it seems likely now that the next administration will be formed by the two dominant players of the last one, albeit they might seek a new partner to bring it over the line.

It is worth dwelling upon that fact.

All over Europe, and around the world, sitting governments have been cast out of office. Since the pandemic hit in 2020, incumbents have been removed from power in 40 of 54 elections in Western democracies, according to a tally by Harvard University that cited “a huge incumbent disadvantage”.

But this Government has one clear advantage: a turbo-charged economy and an Exchequer swimming with cash. Simon Harris may have been criticised for saying that there is a job for everyone who wants one, but the data supports his claim. The country is in full employment, and Ireland’s biggest issue is that it cannot spend the huge sums of money at its disposal.

The surge in the cost of living has been harsh, but it has been also tempered by a string of subsidies and interventions.

The scourge of inflation that has thwarted so many sitting governments has not made its political mark here. The universal income supports have certainly helped.

Our neighbours are moving deeper into austerity and fiscal deficits. Meanwhile, Ireland can afford giveaway budgets, and still stash billions aside for a rainy day.

Social issues were bypassed in the campaign. It says much that the first question Harris faced in his in-depth interview on the Six One News was whether Fine Gael had allocated enough money in its manifesto to cover existing levels of public service.

There is a case to be made that the election of Trump assisted Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael in this election. The uncertainty that Trumpism, and its policy of tariffs, brings brought renewed public focus on the management of the economy and the public finances. In uncertain times, people look for the certainty of what they know.

That is not to say that the government won this general election. In a sense, they survived it.

The Green Party has been decimated. The party was outflanked by Labour, the Social Democrats, and in certain constituencies, by People before Profit. Junior coalition parties tend not to do well in elections. But this seems different, more visceral.

The Green Party argued on the doorsteps that it had successfully implemented many of its policies. In response, voters opted to cut the party loose.

To his credit, Eamon Ryan rebuilt the party after its last time in government between 2007 and 2011 when the economy collapsed. The scale of the reconstruction for the party seems bigger this time.

For his part, Simon Harris was bruised during the campaign. It went beyond his Kanturk moment. His campaign, and, for Fine Gael, it was a campaign based around him, failed to ignite or convince. Fianna Fáil had a better ground game, and, with its coalition partner losing a sizable number of its incumbent deputies, a better roster of candidates. Simon Harris sought to bring energy to the campaign. Micheal Martin, by contrast, brought composure. His calm resonated.

The big issue for the two parties is whether the seat numbers will be close enough to ensure a rotating taoiseach and parity of esteem. In the build-up to the ballot, the magic number seemed to be in the region of ten seats – if one party had ten fewer seats, then a rotating Taoiseach might not be on. As it stands, that number could be reached.

Sinn Féin will no doubt point to successes, but it has yet to establish a credible path to power. It runs the risk of being caught in political purgatory; one of the triumvirate of large parties, but lacking a willing partner to coalesce with. It will argue that it has been locked out of government by incumbents, pointing to a narrative of political insiders and outsiders. Yet, despite five years as the main party of opposition, it has not moved any closer to power.

Having a permanent party of opposition is not good for any democracy; it will make politics more adversarial, more polarised, and more unpleasant.

The Social Democrats and Labour will have some big decisions to make. It seems that if Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil agree to a deal, only one of two soft-left parties may be required. Both Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil would prefer Labour, but the Social Democrats would at least have to entertain the option of joining the government.

Both will look at the fate of the Green Party with trepidation. After all, when the dust settles, it seems this election has been little more than a reallocation of the Green Party’s seats to other parties.

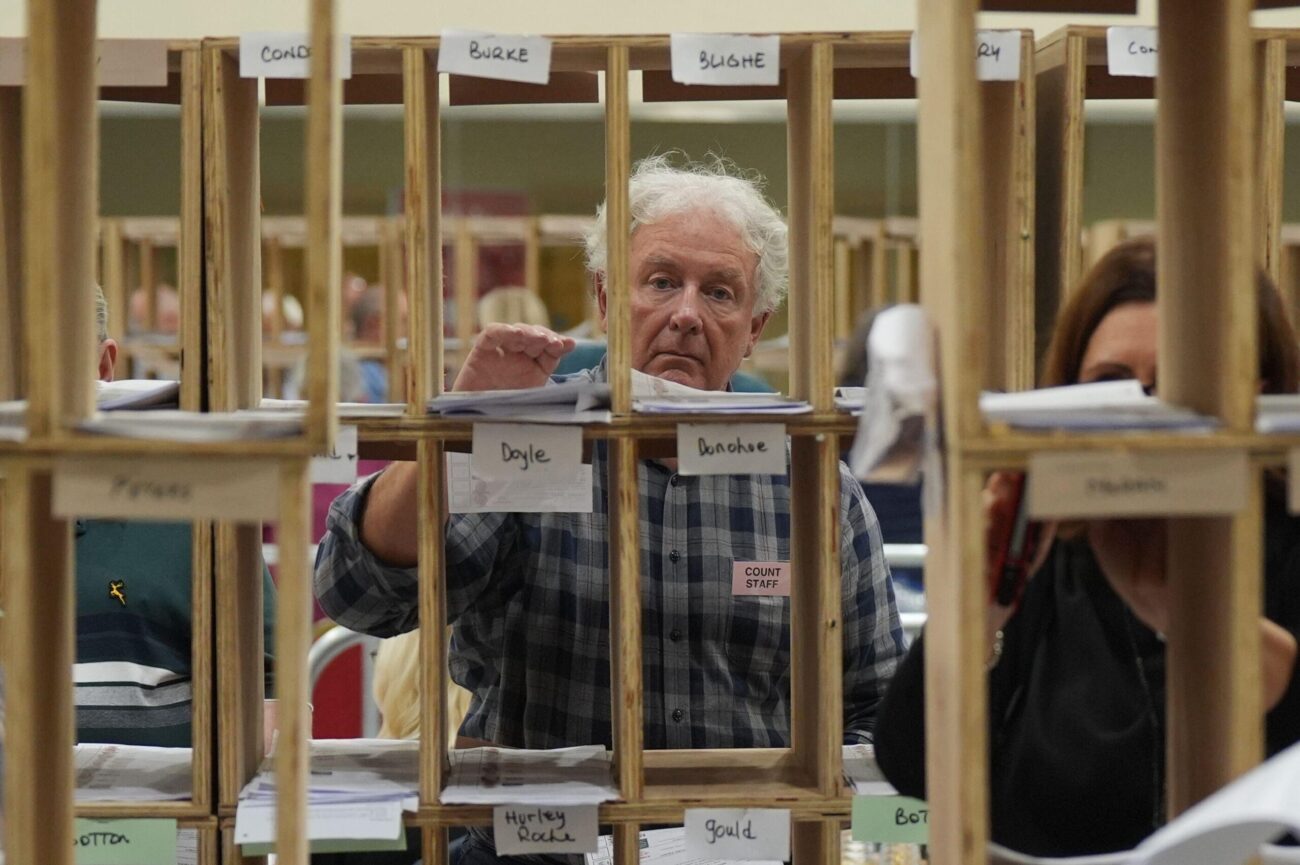

It will be some time before we know where all the seats have fallen. A small number of marginal seats could yet make a big difference, and the pattern of transfers will have a huge impact in determining the final seats around the country.

There was no political earthquake here, no redrafting of Irish politics. Major political figures, including ministers, will become casualties. Plenty of incumbents will lose out.

Overall, however, a sizable number of people looked at the status quo, and, despite its many deficiencies, opted it was in the round, the best option.

Elsewhere last week…

On Monday, Judge Martin Nolan sentenced Brendan Mullin, the former rugby star, to three years in prison for stealing more than €500,000 from the Bank of Ireland. Mullin had denied all charges against him, but a jury returned guilty verdicts in 12 of the 14 charges against him. In a two-part special last week, Tom delved into the rise and fall of Mullin.

In part one, he explored how Mullin sought to navigate the corporate world with the ease he played rugby. In part two of his report, Tom examined the money trail and the attempts by Mullin to rehabilitate his finances.

I sat down with IDA Ireland chair Feargal O’Rourke to talk about Trump’s trade policies, his late mother Mary, and his new book on the Irish men’s rugby team, while Tom spoke with Accenture Ireland boss Hilary O’Meara, who leads a team of 6,500 people in Ireland.

The Dublin finance firm Blacksheep, founded by Alexis Fortune and Alan Burke, has secured a stake in Distilled Ltd. Michael explained the rationale for the deal and what we know about Blacksheep.

Four years ago, Patrick McCormack led the €14m rescue deal for the Cara Pharmacy Group. Working with CFO Conor O’Reilly, he has rebuilt the group from the ground up. McCormack and O’Reilly explained the turnaround and revealed their future plans.