A Fine Gael minister once explained to me how he categorised Michael Lowry losing a defamation action against me in the High Court back in 2012: “It’s not personal, it’s just business.”

I am not so philosophical: It was very personal to me.

Had I lost, the disgraced former minister would have ended my career as a journalist and put me out of house and home.

Lowry contended that I had defamed him on the Tonight with Vincent Browne show on TV3 on June 24, 2010.

Mr Justice Nicholas Kearns, the High Court judge who considered Lowry’s allegations against me, repeated in his February 10, 2012 judgment what I said that so enraged Lowry that he sought to go after me personally in the courts.

This is the transcript of the show as taken from the Kearns judgment:

Sam Smyth: “But the first that we caught sort (sic) on video with hand in till was Michael Lowry and he resigned as you might remember as Minister for Communications which all this has led on from.”

Vincent Browne: “Now let’s be clear now, let’s be careful about the hand in till. There is no suggestion at all anyway that Michael Lowry used his position as Minister to extract public funds that weren’t, that he wasn’t entitled to.”

Sam Smyth: “No but was in receipt, in allowed? The biggest business in the country to pay for the refurbishment of his home. I mean…”

Vincent Browne: “There was a tax that was a tax fraud.”

Sam Smyth: “And that well, there was not only a tax fraud, I really don’t think most people think it’s a good idea for Ministers to have their bills picked up by businessmen.”

Lowry contended in his legal filings that these words meant he was “a thief, a corrupt politician, unfit to be a TD or Government Minister and was or is a dishonest or untrustworthy politician”.

He also sued me because of an article published in The Irish Independent on May 27, 2010, with the headline: “Tribunal will reveal findings on money trail to ex-Minister.”

In the article, as repeated by Justice Kearns, I wrote: “The total value of all the property transactions involving Mr Lowry was around 5 million pounds sterling.”

According to Justice Kearns: “[Lowry] complains that these words in their natural and ordinary meaning and/or by way of innuendo meant and were understood to mean that the plaintiff had unlawfully benefited from transactions concerning property valued at stg£5m by awarding a mobile phone licence while he was Minister for Communications and had the other meanings detailed in relation to the television interview.”

Lowry sought a declaration that the statements were false and defamatory and wanted an order prohibiting those statements from being published again, as well as summary relief against me.

I responded by saying the language I used in The Irish Independent and on TV3 was a fair and reasonable publication on a matter of public interest and that Lowry was found to have engaged in tax evasion and lied about his business and financial affairs.

In his ruling on that memorable day in February 2012, the president of the High Court said that I was entitled to express an honest opinion on matters of public importance.

Mr Justice Nicholas Kearns also noted that although the Defamation Act 2009 appeared to be addressed to newspapers or television, Lowry had not joined either Independent Newspapers or TV3 in his application.

Furthermore, Lowry’s legal action had not sought corrections or apologies from The Irish Independent or TV3, the publishers of the journalism that he had claimed was defamatory.

As the sole named defendant, I was at the epicentre of his accusations and I was very fearful at the prospect of bailiffs acting for a wealthy politician seizing my modest home and meagre assets.

I was also determined not to buckle to a disgraced politician.

Lowry wasn’t in court but I was relieved when the president of the High Court vindicated me and ordered that Lowry pay my legal costs.

Justice Kearns said he was satisfied that I could “argue that the words ‘hand in till’ in their correct meaning may be taken as referring to tax fraud and bills inappropriately picked up for the benefit of the plaintiff by business interests”.

He added: “The fact that Dunnes Stores paid £395,000 to the contractors who had refurbished his home in Co Tipperary and that the plaintiff was availing of offshore accounts to receive other payments are also matters capable of being established in evidence other than exclusively through evidence or findings of any tribunal of enquiry.”

Justice Kearns said: “In this context, I note that the plaintiff in his various affidavits does not dispute that he had engaged in tax fraud, although he deposes that his tax affairs are now in order having reached a settlement with the Revenue in 2007.” In relation to the article in The Irish Independent, it is equally open to the defendant to report and comment on the fact, as fact it was, that the Moriarty Tribunal was following a ‘money trail’ into certain property transactions to which it felt the plaintiff was linked and which had a combined value in the region of stg£5m.

“The Carysfort Avenue transaction involved an examination of a sum of stg£147,000 moving from accounts involving the plaintiff. The Cheadle and Mansfield property transactions being investigated had valuations of stg£445,000 and stg£250,000 and the Doncaster Rovers property transaction had an approximate value of stg£4.3 million.

“I am satisfied therefore that it cannot be said that the defence of this claim must necessarily fail. On the contrary, it seems clear that the defendant has a good arguable case in respect of both publications.”

Having established that I could defend myself, Lowry did not pursue his claim further.

But as I heard this judgment, I wondered again if Lowry’s action against me really was “not personal, just business”.

Lowry’s defamation case against me felt extremely personal. And it came with a history: He had sued me personally before, of which more later.

The unchallenged legacy of Moriarty

The findings of the report of the Moriarty Tribunal were accepted as the truth 14 years ago in a non-contested all-party Dáil resolution that called for Michael Lowry’s resignation.

There are many findings of the Moriarty Tribunal in relation to Michael Lowry that are worth recalling, including this one.

Michael Lowry, according to the Tribunal’s report, tried to use his influence to double the rental value of a building part-owned by businessman Ben Dunne and leased to the then State-owned Telecom Éireann.

If this attempt had succeeded, the tribunal found it would have doubled the value of Dunne’s building from IR£5.4 million (€6.86 million) to IR£12.75 million (€16.19 million).

“What was contemplated and attempted on the part of Mr Dunne and Mr Lowry was profoundly corrupt to a degree that was nothing short of breathtaking,” the tribunal report said.

“What was reprehensible about his actions was that the tenant of the building was Telecom Éireann, of which, as minister for communications, Mr Lowry was the ultimate shareholder.”

Reading the findings into the record of the Dáil in 2011, the now leader of Fianna Fáil, Micheál Martin, said it was “beyond doubt” that as minister for communications, Lowry gave “substantive information” to businessman Denis O’Brien about the competition for the second mobile phone licence, the most valuable licence ever awarded by the State at that time. Lowry was an “insidious and pervasive influence” who engaged in a “cynical and venal abuse of office.”

Martin added: ”We therefore believe Deputy Lowry should consider his position and resign from Dáil Éireann.”

Then Fine Gael leader Enda Kenny said: “We must rehabilitate the idea of civic virtue and the idea of the duty and the nobility of public service.”

Both Michael Lowry and businessman Denis O’Brien rejected the findings of the Moriarty tribunal but have never challenged them legally.

Then, now, and this

That was politics then, and this is politics now.

Martin, today the Taoiseach, and Fine Gael’s leader Simon Harris, today the Tánaiste, allowed Michael Lowry to become kingmaker during government formation talks.

Lowry demanded and got nearly everything he sought for the Regional Independents Group (RIG) beginning with the position of Ceann Comhairle, one of the most senior and highest-paid (€255,000) elected members of the Dáil.

It was a deal that has triggered trouble for the Government. For a start, it united the opposition parties and the majority of public opinion opposing the RIG deal with the government.

The appointments also raised questions about Martin, one of the few times he has been under serious pressure since assuming the leadership of his party in 2011. Why did one of the most trusted of our politicians allow Lowry inside the government tent?

Even enemies do not dispute Lowry’s great political skill in both government and opposition or his impressive organisational capability.

Lowry’s assets and talents are hallmarks of an intuitive and persuasive tactician conjoined to a shrewd salesman and strategist.

Just how did it come to this?

Big money and political power

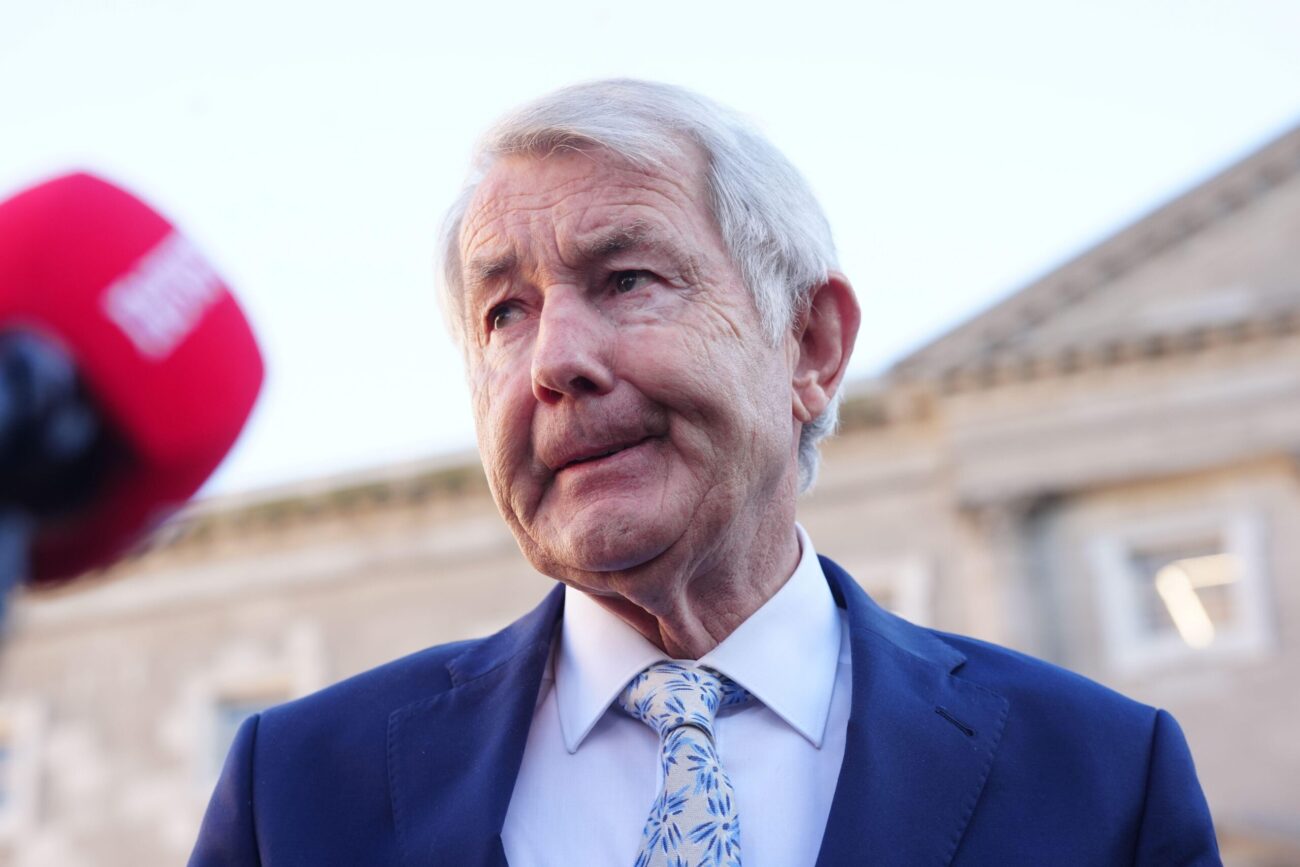

Now almost 71, Michael Lowry is wealthy and has even wealthier friends, plus now he has a couple of his associates at the cabinet table, where once he was himself, as super junior ministers.

As recently as January, Lowry said he was “fully confident” he has no liability as a file was sent to the DPP over the Moriarty Tribunal’s findings. He issued a statement saying:

“I learnt, with surprise, from newspaper reports this morning that it has been stated that a file has been sent by An Garda Síochána to the DPP arising from findings of the Moriarty Tribunal.

“Last year, I received a request for assistance from An Garda Síochána. I freely, voluntarily and willingly met with them on one occasion and was fully co-operative. This was the only engagement or correspondence I had with the gardaí over the 14 years since the report was published.

“At no point, on that occasion or since, was it suggested that there were or are any charges being contemplated against me. I am fully confident that there is no basis for any liability attaching to me.

“All those involved, including myself, have steadfastly maintained that there was no wrongdoing or impropriety attached to the award of the GSM licence, some 29 years ago.”

That swaggering confidence came at the same time Lowry was acting as a central figure in the formation of this Government.

Forever protesting his innocence while flourishing his influence, Lowry has been returned as an independent TD at every election since his disgrace and resignation from Fine Gael in 1996.

He tried to exorcise old ghosts from the Moriarty Tribunal, protests his innocence of all and ignores a conviction for tax evasion where he (Lowry) and his company were accused by a State prosecutor in June 2018 of “cooking the books, not just once but twice”.

Lowry’s fusion of ambition and greed was illustrated vividly in the 1990s when he persuaded Ben Dunne to secretly pay hundreds of thousands of punts to refurbish his home. His effectiveness in politics is reflected in his success and business.

If he had not been banished from Fine Gael, Michael Lowry would almost certainly have followed John Bruton as leader of Fine Gael.

Lowry, a farmer’s son from a modest rural family, seemed to have an instinctive understanding of the symbiotic relationship between big money and political power. Bruton, whose wealthy family had inherited a large farm, viewed political fundraising as demeaning. As leader and Taoiseach, he let Lowry do the grubbing to fund Fine Gael.

I observed Lowry’s vertiginous rise from full-time fridge engineer and TD to multi-millionaire and government minister. Later I noted his mode of transport, moving from his personal top-of-the-range BMW to the backseat of a perhaps more modest ministerial Mercedes.

From his election in 1987 until his resignation in disgrace as a minister in 1996, he enjoyed nine years of non-stop success.

After shepherding John Bruton to leader of Fine Gael and eventually Taoiseach, Lowry became perhaps the most powerful man in government. After negotiating the programme for government for the Rainbow Coalition in 1994, he could have chosen any number of cabinet portfolios and became minister for transport, energy and communications.

He was also chairman of the parliamentary party, he was director of finance and chairman of Fine Gael’s trustees. He is widely credited with clearing the party’s debts and scouring significant sums from donors, Ben Dunne included.

The new Taoiseach trusted Lowry. Lowry hit the ground running as a minister, provoking confrontations in the semi-state sector.

He claimed to The Irish Times in August 1995 that, “Shortly after I first arrived at my desk [as Minister] I started to receive complaints from a substantial number of business people who felt they were excluded from the system. It was evident to me that a cosy cartel was in operation.”

His valiant efforts to smash this “cosy cartel”, he claimed, had led to him being put under “sinister” surveillance.

He also told The Irish Times about his concerns about the “growing issue of fraud” in the wider Irish economy as he announced a new task force to review governance controls in all semi-states.

“It would be naive to conclude that State companies are removed from the risk of fraud and white-collar crime. For this reason, we must be confident that strong controls as opposed to guidelines of good conduct are in place”.

Lowry was portrayed as a cool, clean hero.

After making his allegations about being under surveillance, investigations were demanded. The gardaí responded that it was not illegal to put anyone, even a government minister, under surveillance. No law was broken, so no Garda investigation was required.

Some journalists were later told that it wasn’t Lowry but a woman who was the subject of surveillance. But what actually happened, if anything, never became public.

The task force of 11 wise men drawn from the elite of the civil service that was asked by Lowry to examine whether Ireland’s semi-states had the proper controls in place concluded their report in October 1995.

“Lowry’s ‘cosy cartels’ statements had created the impression that he was aware of widespread abuse in the sector,” Cliff Taylor wrote in The Irish Times after publication of the task force’s report.

“However, the task force he established to look at the purchases of goods and services, the sales of assets and the internal audit functions in the semi-states concluded that controls and procedures were ‘basically sound.’”

In the wake of this controversy, I was asked to appear on RTÉ’s Prime Time in November 1995 where the author of anonymous letters made scurrilous and fantastical lies and libels about Lowry. Before it was broadcast, I had checked out the author, Patrick Tuffy, with the Institute of Chartered Accountants and learned that he was unfit to appear. I told RTÉ executives that their anonymous letter writer, Tuffy, had been struck off as an accountant. Consequently, I was ultra-careful with my language on air when I appeared live with fellow panelist, the journalist Emily O’Reilly.

The programme was subsequently relabelled as “Tuffy’s Circus” and it was obvious the programme was ill-prepared and deeply flawed.

A few days later I wrote a story for the Irish Independent: “[Pat Tuffy] is a self-confessed liar, a forger who is forbidden by law to practice as an accountant and a bankrupt who would do anything for money.”

Lucky Lowry transformed to Litigious Lowry and instituted defamation proceedings against Pat Tuffy, RTÉ, me (again personally) “seeking exemplary damages for the most grievous and unwarranted libel.” Emily O’Reilly was excluded.

After an exchange of letters with my solicitor, RTÉ’s legal department indemnified me against any legal costs or a future settlement of the case. I felt Lowry, by suing me personally, was reminding me of the potentially ruinous cost of reporting on him.

The threat of libel action hung heavily over me and curbed my inquiries into Lowry as he became embroiled in a controversy in the mid-1990s with the visionary businessman Eddie O’Connor, who then led Bord na Móna.

Sources kept me informed about his handling of the second mobile phone licence, which was, in 1995, the biggest contract ever awarded by the Irish Republic, but that wasn’t the focus of my attention yet.

Ben Dunne and all that

I had covered Ben Dunne’s fall from grace in a suite on the 17th floor of a hotel in Florida and Dunnes Stores vast and very profitable business empire.

I never wondered why Dunne had chosen Michael Lowry to take care of his family company’s refrigeration needs — not until I received a call in October 1996 asking me to meet a contact.

He asked if I knew that Dunnes Stores had paid for the refurbishment of Michael Lowry’s home in Tipperary. Ben Dunne had made the financial arrangement privately with Lowry and, he said, the work on the property in Tipperary had been completed by Dunne’s architect and builder.

The costs of the refurbishment to Lowry’s House in Tipperary were charged against the Dunnes Stores outlet in the Ilac Centre in Dublin.

I needed proof and the documents were delivered in the carpark of the Yacht bar in Clontarf. A lawyer for The Irish Independent was duly impressed by the veracity of the documentation and the detail in my story.

The editor, Vincent Doyle, gave the go-ahead and chartered a light plane for aerial photographs of Lowry’s refurbished home in Tipperary. Despite frequent calls all day, Minster Lowry refused to comment on the story. The next morning, November 29, 1996, the story was splashed across the front page of the newspaper.

All that day, the government was incoherent and confused but that evening, after interviewing Lowry, Charlie Bird of RTÉ was telling his friends that Dunnes Stores had given £1 million to another politician. The name of Charlie Haughey emerged in the following days.

Lowry’s resignation, the day after we published, left a gaping hole at the political heart of John Bruton’s government. And the Rainbow Coalition haemorrhaged credibility from their big public spending plans through their general election campaign.

Failure by the Coalition in the June 1997 election was trumped when Bertie Ahern was elected Taoiseach. And the loss of face encouraged the Rainbow coalition to blame their loss on a critical front-page editorial in the Irish Independent.

Like jealousy, schadenfreude — taking pleasure in another’s misfortune — is a dish best served cold so I said and did nothing after Lowry dropped that first defamation action against me and RTÉ.

The children of the founding fathers and sorrowful mothers of Irish independence were left nursing the shame of the shameful successors.

The Government instituted an investigation with an unforgettable name: The Payments to Politicians Inquiry. It would focus on just two targets: Charles Haughey, who led four Fianna Fáil governments as Taoiseach, and Michael Lowry, a minister for two years in a Fine Gael government.

It was followed by the Moriarty Tribunal. Its findings posthumously shamed Charles Haughey and the Dáil passed a resolution recommending Michael Lowry resign his seat. Lowry rejected the findings but chose not to challenge them in court.

In January, Michael Lowry told RTÉ’s This Week that he had delivered a letter to the Ceann Comhairle, requesting an opportunity to make a personal statement to the Dáil to address a “smear” against him that he alleged had been made by Sinn Féin TD Pearse Doherty.

Lowry never did so, however.

Lowry broke a sacred trust with the Irish people as a government minister, as was repeatedly highlighted by the Moriarty Tribunal.

Like the then Taoiseach and the Tánaiste, the leader of Sinn Féin, and all of the members of the Dáil, I concur with every finding, including corrupt behaviour, made about Lowry by the Moriarty tribunal. And yet after all this history, Lowry has reemerged on the political stage as a would-be kingmaker.