We have learned one thing from a week of headlines dominated by US President Donald Trump and French opposition leader Marine Le Pen.

For all the simple answers they offer to complex problems, far-right populists can be trusted to generate one thing: uncertainty.

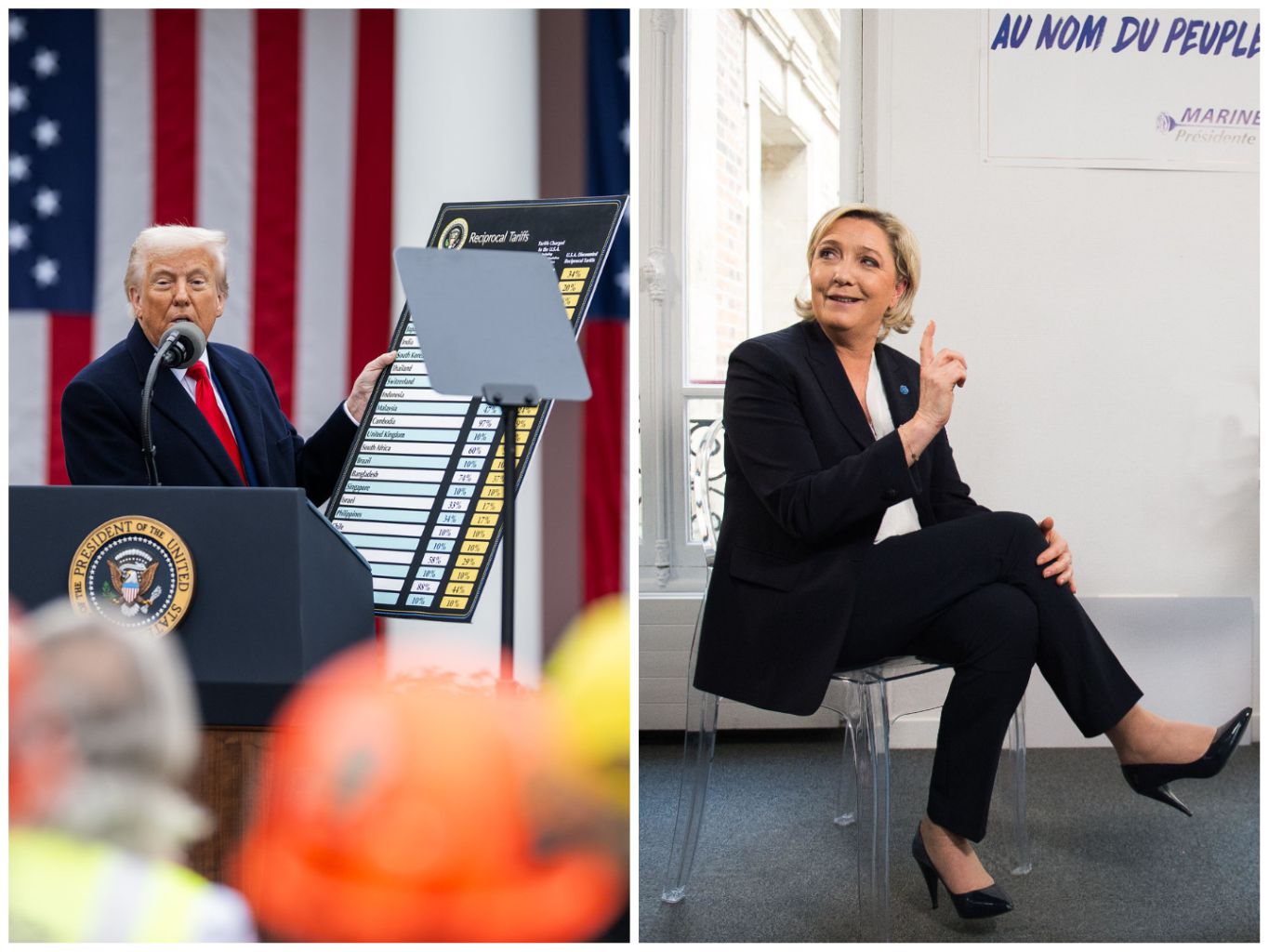

Trump’s studiously haphazard announcement of US tariffs not seen in a century was designed to cause confusion. His speech in the White House’s Rose Garden on Wednesday described new duties of 10 to 50 per cent as “reciprocal” to various costs, monetary or not, he claimed trading partners imposed on US products.

The White House later clarified that they were nothing of the sort, instead being based on a crude measurement of the current trade deficit in goods between the US and other markets that left the EU facing a new 20 per cent tariff in transatlantic exports.

Documents distilled by the White House during the rest of the week first indicated that “pharmaceuticals, semiconductors” and other products were exempt, prompting an audible sigh of relief among Irish-based multinationals accounting for most of Ireland’s exports to the US – and the Government their taxes bankroll.

Then Annex II to Trump’s executive order was published, listing those products actually exempt. It showed that medicines and their ingredients were indeed included, but medical devices weren’t. Annex II indicated that the actual legal text implementing the new tariffs was in Annex III, which was nowhere to be found.

After a couple of attempts typing “Annex-III.pdf” instead of “Annex-II.pdf” on the White House’s website, I stumbled upon it on Friday. It’s here for any trade experts trying to figure out what exactly is going on.

And this is only the start. Trump’s announcement is a mere opening position in trade and diplomatic negotiations, as the Canadian and Mexican precedents have shown. With a one-week window before the 20 per cent tariff on the EU applies, the muted response from Brussels so far can be summarised as: “Game on, let’s negotiate”.

With talks now underway behind the scenes, any businesses trying to prepare for the new world order are blocked from making any informed decisions.

Whatever final duties apply both ways will redefine global competition. Irish exporters to the US will not only need to re-assess their supply chains and pricing in the light of their own tariff costs, but also consider that their competitors face duties that may now be lower or higher by a factor of up to 2.5.

Then comes the prospect of US corporate tax reform, with unpredictable dynamics set to develop between Trump and a Congress where signs of discomfort with his wrecking-ball approach to economic policy are appearing.

“It is of course still possible that a negotiated outcome will see tariffs averted.”

Martin Shanahan, Grant Thornton

In a remarkably fast analysis of the drip feed of information from the White House, Ibec has estimated that the tariffs announced so far would target one quarter of the value of Irish exports to the US. While this is no consolation to those directly in the firing line, such as dairy and spirits manufacturers, Ibec’s figures translate into a loss of less than one per cent in overall Irish exports.

The true impact on the economy, however, lies elsewhere. “Uncertainty may be the biggest short-term barrier to growth,” the business group warned, setting the tone whomever you turn to.

Brokers? “The tariff agenda has disrupted global trade and driven a spike in uncertainty, potentially inducing a recession in the US and slowing global economic growth” (Davy).

Government? “Tariffs are economically destructive; they drive up the cost of doing business and put upward pressure on prices for consumers, all the while creating uncertainty for investment and future growth” (Minister for Finance Paschal Donohoe).

Economists? “Any hopes that the new tariff plan will eliminate uncertainty seem optimistic. As we’ve shown, a longer period of heightened tariff uncertainty may impact overall GDP growth and investment” at the global level (Oxford Economics).

Grant Thornton’s newly minted international head of industry Martin Shanahan added: “It is of course still possible that a negotiated outcome will see tariffs averted.”

A rare spark of stability came from Exchequer figures released on Thursday, when Ireland’s tax take continued to grow. Corporation tax paid in March, especially, comes almost entirely from Apple. Excluding the effect of last year’s state aid court decision, this was back on trend after wild variations caused by restructuring in Apple’s Irish tax structure in the past two years.

The IT multinational is again posting a slow but steady increase in Irish tax payments, in line with its international profits. Trump’s tariff announcements, while posing a threat to Apple’s US imports from outsourced manufacturers in Asia, in fact reinforces the firm’s decision to use Ireland as a base for the 60 per cent of business it does outside America.

Apple’s Cork office orders devices from manufacturers in places like China and has them shipped to final markets stretching from Portugal to Japan, without them ever showing up in the US. The more severe the trade war between Trump and the rest of the world, the better insulation this Irish-based model will provide for Apple.

Convicts posing as victims

Two days before Trump’s “liberation day”, his French cheerleader Marine Le Pen was sentenced to a €100,000 fine and four years in prison (of which two were suspended and two to be served under house arrest). She, her National Rally party, and 23 colleagues were convicted for embezzling European Parliament funds between 2004 and 2016.

A Paris court also banned Le Pen from running for office for five years. Using the highest penalty available under French law, the judge ruled that this ban would remain in place pending any appeal, which would excluding the candidate currently leading in the polls from the 2027 presidential election. The judgment found that this was in the interest of protecting the election from the winner potentially being found ineligible after the fact.

The sentence offered Le Pen an opportunity to take a leaf out of Trump’s book and pose as a victim of an allegedly politicised judiciary. “Some judges have used practices thought to be the preserve of authoritarian regimes,” she said in a TV interview after her sentencing. “The rule of law was violated.”

This glossed over the fact that she brought the wrath of justice on herself by presiding over a long-term scheme to staff her party’s head office with assistants paid by the European Parliament to do parliamentary work. They ran the national organisation and barely showed up, if at all, in Brussels and Strasbourg.

While there was no finding of personal gain, the Parliament estimated the embezzlement of payroll funded by EU taxpayers at €7 million. The National Rally was sentenced to repay €4.4 million of this.

“Sounds like a ‘bookkeeping’ error to me,” Trump posted on Friday on his platform Truth Social, denouncing a “witch hunt”.

The French political response to the case has been contrasted, not just because some of Le Pen’s opponents are uncomfortable with a potential pyrrhic victory in the next election.

Prime Minister François Bayrou said the harshness of her immediate election ban raised “questions” and the leader of the next largest opposition party, leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon, commented that elected officials should “only be removed by the people”. This may have to do with the fact that both men face prosecution in similar, though smaller-scale, cases of misuse of European Parliament staff at their party’s headquarters.

It’s not as if they didn’t know. The bogus employment of party officials on state bodies’ payroll has been the mainstay of corruption in France since the 1980s, when then-Paris mayor Jacques Chirac borrowed from city hall ranks to staff the political machine that would make him president. His heir apparent and former prime minister Alain Juppé took a bullet for him when a related conviction for embezzlement ended his political career in 2004.

A lot can happen in two years. A Paris appeals court has committed to hearing Le Pen’s case next year, well in time for the election. The reaction of the French street has yet to be factored in, with protests scheduled this Sunday.

There is a strong chance that she will run in the 2027 election. Like Trump, she would then drum up additional support with claims that “the system” tried to take her down. Being perceived as too much of an established parliamentary opposition party is not good electorally for populists (ask Sinn Féin).

Le Pen is far from being out of the race to lead France. She’s very much still in the game when it comes to fuelling uncertainty.

*****

Elsewhere this week, the alleged corporate espionage case opposing HR technology multinationals Rippling and Deel was back before the High Court, where Alice and Tom covered proceedings. In an explosive affidavit, the alleged spy, Keith O’Brien, made extraordinary allegations about Deel and its CEO, leading the judge to join them as co-defendants. Deel has denied all accusations.

A referendum on fully joining Europe’s new patent court was shelved last year. Since then, the EU’s Unified Patent Court has rumbled on with issuing decisions while Ireland waits on the sidelines. Jonathan explored the situation with visiting UPC judge Kai Härmand and Irish experts.

Since a report released by the Department of Arts in February exposed the waste of €5.3 million on a failed IT revamp project at the Arts Council, little had been heard from the agency itself. Niall obtained internal documents from the project’s post-mortem putting its main contractor in the firing line, as well as the first public response from the contracted company, Codec.