Sometimes, to think about the future, you have to look to the past.

When assessing the forthcoming election of the State’s tenth president, it is worth looking back at the priorities of the fourth incumbent of the office.

Erskine Childers received 635,867 votes, or 52 per cent of the ballot. He was 67 when he was inaugurated in 1973, and he sought to bring energy and vigour to the office. However, his efforts to redefine the presidency, making it more hands-on, brought him into conflict with Fine Gael Taoiseach Liam Cosgrave.

Specifically, Cosgrave rebuffed a plan by Childers to establish a think-tank within Áras an Uachtaráin. Fianna Fáil’s Childers wanted an institution to dream about what the State should be, about the sort of country that we want to develop. Yet, in those helter-skelter partisan days, it was shot down as too political, too risqué.

Childers was ahead of his time. Successors such as Mary Robinson, Mary McAleese and Michael D Higgins would develop that sort of national conversation, that social debate, albeit without the backstop of an in-house think-tank.

Childers viewed the office as a means to begin a conversation. Beyond politics, he believed it was a mechanism for looking at the nature of society.

As the election of our next president draws near, there is a lot of merit to his thesis.

The parliamentary system in Ireland does not allow for long-term thinking. Elections need to be called, and elections need to be won. Long-term, strategic thinking is far too often overruled by electoral imperative. We talk a lot about the future, but we do not plan for it.

That is why the office of the president matters. It can set the tone for a national conversation.

And, we have been blessed by the calibre of our presidents in recent times and the capacity to spark that conversation.

Patrick Hillery brought calm and integrity to the office at a time when the general political system was fraught, fragmented and ferocious. Mary Robinson triggered a wider debate about equality and women’s rights. The country was ready for that conversation at that time, and Robinson was the perfect person to develop the conversation. She pushed the boundaries of the presidency, but the public was happy for her to do it. She was of a time and place.

So too was Mary McAleese, who took over as the conversation about the relationship between North and South was escalating, and as the country challenged its relationship with Catholicism. McAleese, a Catholic bridge-builder, was the right person in the right place.

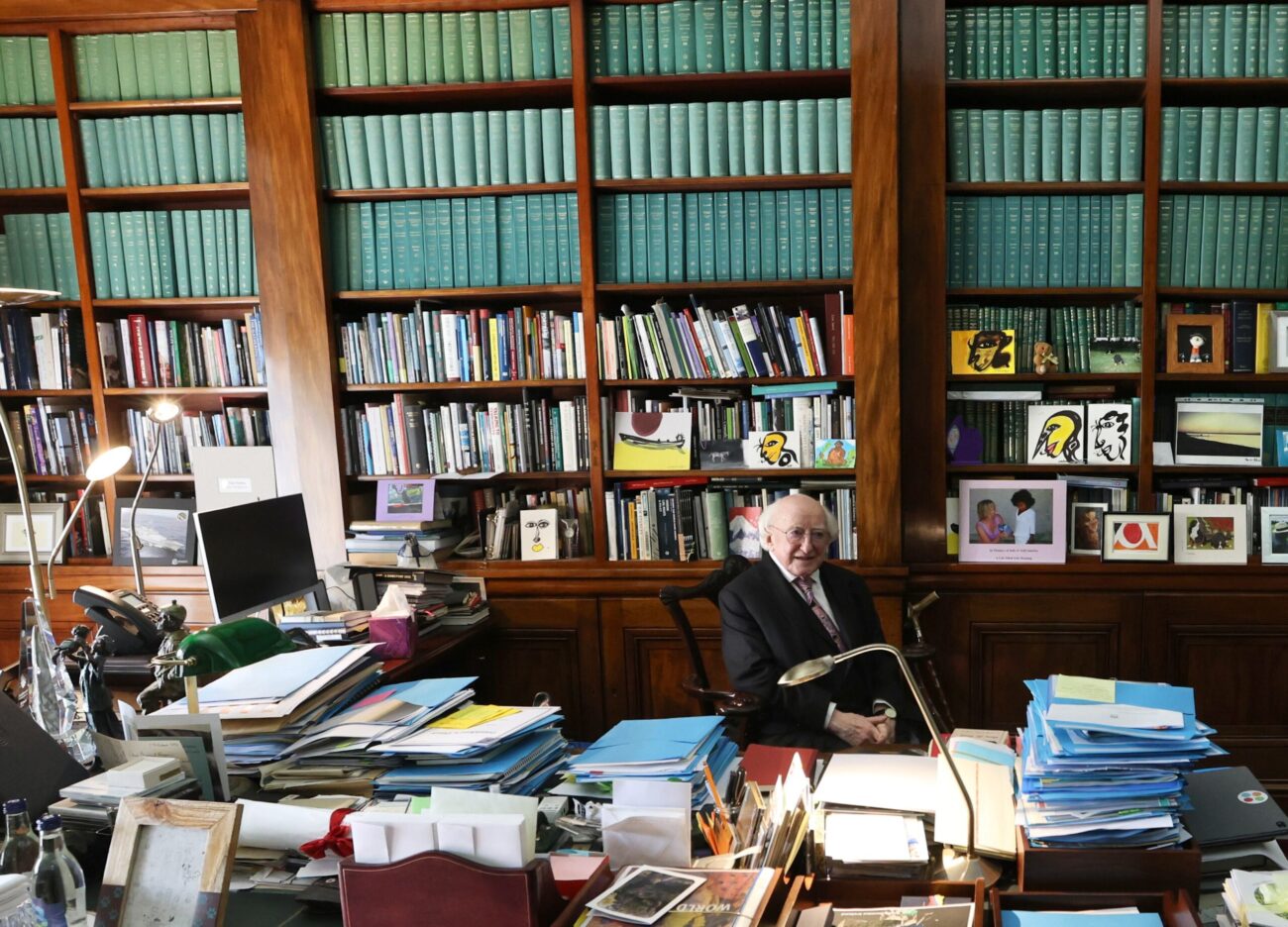

It is too early to judge the presidency of Michael D Higgins – history tends to judge people in its own way and in its own time. But certainly, in his first term, he spoke passionately and compassionately to a country that was dealing with economic collapse and austerity. He has talked about the excesses and the pitfalls of capitalism at a time when the country was picking up the tab for those excesses.

It begs the question: What do we need now from a president?

The international order, as we know, is disintegrating. Multilateralism is collapsing under the weight of Trumpism and populism. The order that we understood and profited from is under siege. Our values are threatened.

Technology is threatening – and elevating – everything.

Perhaps this is the conversation that the next president needs to talk about, as well as addressing what the country needs to look like in the next 20 and 30 years. This is why it is a shame that the ambition of Childers to establish a think-tank was thwarted.

A multitude of candidates want he job. Conor McGregor wants to be president, as does Michael Flatley. Neither will get on the ballot paper. The businessman Gareth Sheridan also wants to run and seems convinced he can get a nomination. As he is discovering, running for president exposes much.

Catherine Connolly will be on the ballot paper. Fianna Fáil has yet to play its hand—likewise, Sinn Féin. The decision by Mairead McGuinness to drop out of the race on health grounds is a huge blow to Fine Gael. But it might tempt another heavyweight such as Francis Fitzgerald back into the race.

Yet, there is the rub. Before we decide on a candidate, should we not decide on what we want the person to do, and on the views they should articulate? We are essentially holding interviews without devising a job description.

If the role of the president is to hold a mirror to society, do we not need a candidate to talk about the type of president they want to be and the type of issues they will champion?

A president must enforce the Constitution. The constitutional importance of the role cannot be underestimated. With our deliberately imperfect separation of powers, the few prerogatives bestowed on the president – to refuse a dissolution of the Dáil, to refer bills to the Supreme Court, and to address both houses of the Oireachtas – are an important part of our system of checks and balances.

The person exercising them doesn’t need to be a lawyer, but they do need to appreciate the unwritten constitutional norms that shape how these should be used. It’s not enough that they’ve read the words of the Constitution and can take advice. They need to understand what those words really mean, and why they were put there in the first place.

The candidate must also be a representative on the international stage – a tool of government policy if you wish. But they must also be a head of State in more than a titular sense. They must ease the transition between different eras and give a voice to the issue of the day. Mary Robinson did it. Mary McAleese and Michael D Higgins also.

As we prepare to elect a new head of state, we should remember that the person we choose will shape the national conversation for the next seven years. They will not fix housing, or immigration, or climate change alone — but they can decide whether those issues remain in the shallow churn of short-term politics or are elevated to deeper, sustained debate.

If we pick our next president only on personality, profile, or perceived electability, we waste the potential of the office.

Elsewhere last week…

Irish digital marketing business Techads claimed to be worth over €600 million but a dispute with a former partner has left the firm hollowed out and existing “solely” for litigation. Jonathan had the story.

Alan Browne, the executive chairman of surveying firm Korec, spoke to Michael about spinning out a new software business with sizable ambitions, working with Formula 1, and the changing face of Irish emigrants.

Receivers from Grant Thornton have appointed an advisor for the sale of several solar power and battery storage projects in Italy that are near the construction stage.

The collapse in new housing starts this year isn’t just a post-incentive hangover – it’s a sign of deeper issues in how Ireland is building, planning, and managing its long-term housing strategy. So said Ronan in his column.