In truth, it never left. But following the big scare of US President Donald Trump’s “liberation day” tariff threats seven months ago, it wobbled.

Now the contribution of the multinational pharmaceutical sector to Ireland’s economy and Exchequer coffers appears to be regaining the momentum lost in post-Covid adjustment and Trump-induced trade turmoil.

The corporation tax take in October, when the only significant taxpayer is Pfizer due to its unusual financial year, returned to its pre-pandemic, billion-euro level. The US group’s Irish tax contributions reflected extreme volatility from the loss of regular business at the start of the pandemic, followed by ballooning profits from its successful Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, and a slump as it restructured following the end of this bonanza last year.

Last month, Pfizer paid the second half of its 2025 corporation tax. In May, when it paid its first half, the Exchequer suffered a €1 billion year-on-year drop in revenue. This was weeks into the launch of Trump’s tariff blitz, and the transatlantic trade in drugs appeared doomed.

Now, as it closes its annual accounts, October’s figures show a near-complete reversal of this move, with a €705 million year-on-year jump. When it comes to profitability and tax liabilities, Pfizer’s Irish-anchored European business appears to be returning to business as usual for the first time in six years.

One participant in a meeting between biopharma industry representatives and Irish government officials this week described the mood as confident, with the main expectation being that everything would be fine. They added that the same group one year ago would have been fearful, expecting the end of days.

The main concern raised by pharma executives was how quickly the State could spend the billions accumulating in the National Training Fund to educate all the skilled workers they expect they will need, the source added.

There was also a sense that the US trade administration led by Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick had been briefed on the practical impossibility of uprooting the pharma industry to relocate it to the US in the short term and understood the message.

Other signals indicate that this may not, in fact, have been the White House’s plan, or at least not recently.

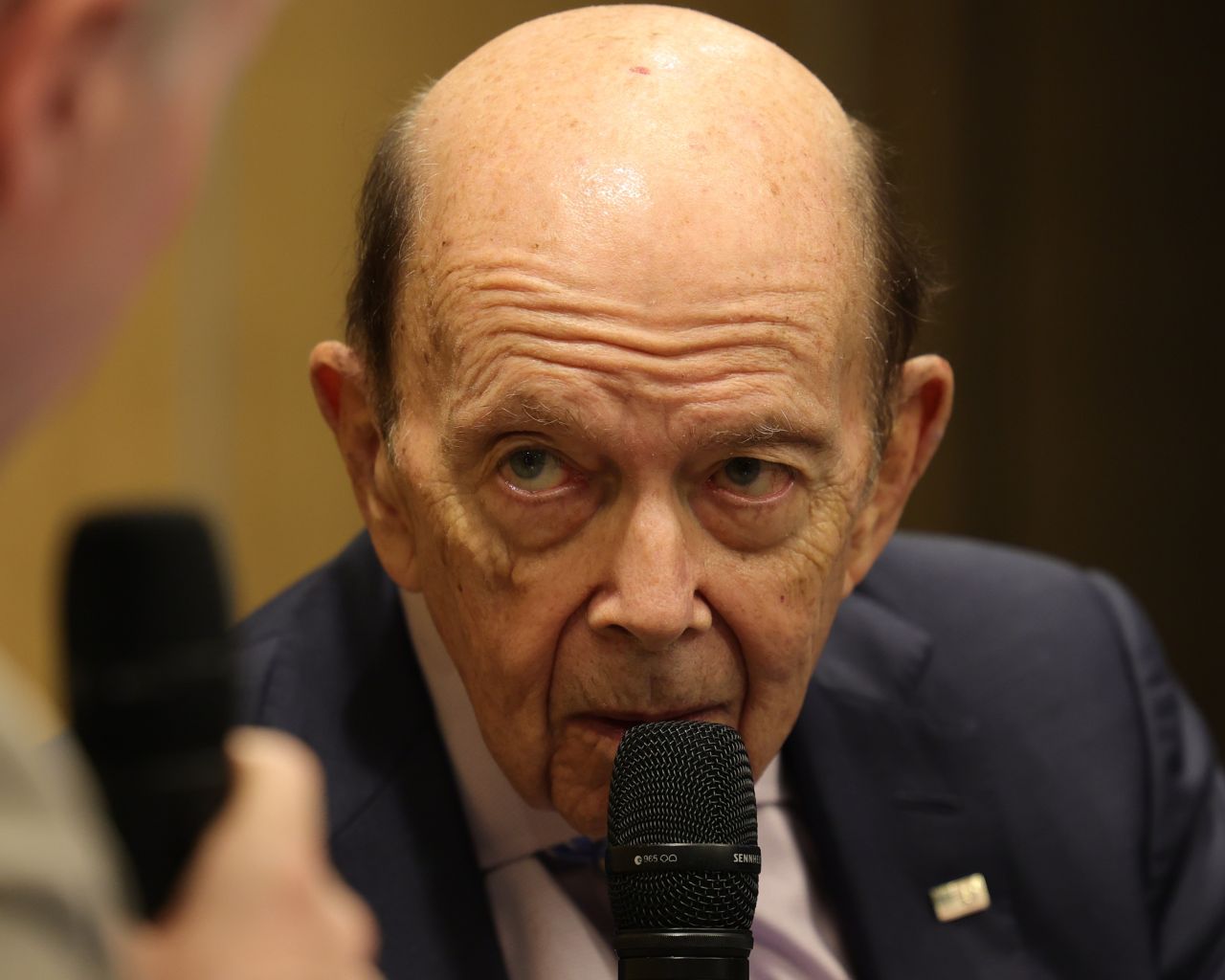

On October 28, the former commerce secretary during Trump’s first term, Wilbur Ross, was in UCD to address the guests of private-equity firm Cardinal Capital, with whom he partnered as an investor in Bank of Ireland to rescue the lender from the financial crisis in 2011.

Ross was clear that he no longer has a role in the Trump administration, but he remains a staunch supporter of the US president and understands his thinking. He spoke with journalists before the main event, and the impact of American trade policy on the Irish pharma industry was top of the agenda.

Ross said the “gnashing of teeth is a little bit overdone” on this issue. “Trump’s real complaint about the pharmaceuticals is that Americans pay much more for the same pharmaceutical than Europeans, Irish or anybody else, and he’s not going to let that stay,” he said. “But as those companies gradually come around – and Pfizer already came around pretty well, I think you’re going to see several of them do it – that’ll relieve some of the tension. So it may be that pharmaceutical employment here won’t be the big growth engine that it has been, but I don’t think people are going to run away from Ireland.”

I asked Ross whether he meant tariffs were mainly a bargaining chip in price negotiations with drug manufacturers, with maybe a bit of US-based manufacturing thrown in.

“The actual cost of manufacturing pharmaceuticals is very low. What really drives the price of pharmaceuticals is the R&D and the regulatory approval process,” he replied, which explained why drug makers could sell their products cheaper in other countries than they do in the US. “They don’t actually lose money on the low prices that they get paid in other countries in terms of direct cost. So that’s what I meant when I said that the president is quite determined, and I think will succeed in more equality of pricing, which is going to mean the rest of the world maybe pays a little more than they have, hopefully we’ll pay a little bit less.”

Ross’s reading that Trump’s “determined” objective to get a deal with big pharma is more focused on price than on provenance appears to be confirmed by the past week’s events.

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly have just agreed deals with the US Government to supply their blockbuster GLP-1 weight-loss drugs at a fraction of their current price to American patients through state-sponsored health insurance schemes and via a new government-run online pharmacy marketplace called TrumpRx, due to open in January.

As mentioned by Ross, Pfizer was among the first big pharma groups to cut a deal with Trump on September 30, announcing price cuts averaging 50 per cent for US patients on a range of drugs to be made available via TrumpRx.

The site’s branding tells it all: Once cheaper drugs can be marketed to happy American voters under Trump’s name, the remaining threat of US tariffs on their products (so far indefinitely postponed) is likely to evaporate.

As Eli Lilly was closing the deal with the US administration, it also announced a €2.6 billion new manufacturing plant with 500 jobs in the Netherlands on Monday. For any low-tax, multinational friendly country in Europe, the message was clear: American big pharma is back.

*****

Elsewhere this week, Ian interviewed former Irish hockey international player Lisa Clarke, who founded her branding agency Rowdy Studio in London after being made redundant during the recession. She is now coming full circle and expanding into Ireland.

Jonathan pinpointed explosive court papers in New York, where an Irish property investment fund managed by Mel Sutcliffe’s Quanta Capital has since obtained discovery from the US firm Avenue Capital, which is the financial backer of Dublin-based property lender Relm.

Meanwhile, Thomas traced an unrelated 2022 guarantee for Relm loans secured on a building acquired by Paddy McKillen Jr for his Grafter serviced offices business, which has now translated into a €1.75 million liability for the Dean Hotel Group.

Michael met Andrew Tzialli, the son of refugees who made it to the top of Irish law firm Philip Lee’s London office. He spoke about his career-defining work and the advancement of Dublin post-Brexit.

Joe reflected on the way more efficient aircraft have broken the rule that you need big planes to cover long distances, and how this is redefining the business model of many airlines – including Irish ones.