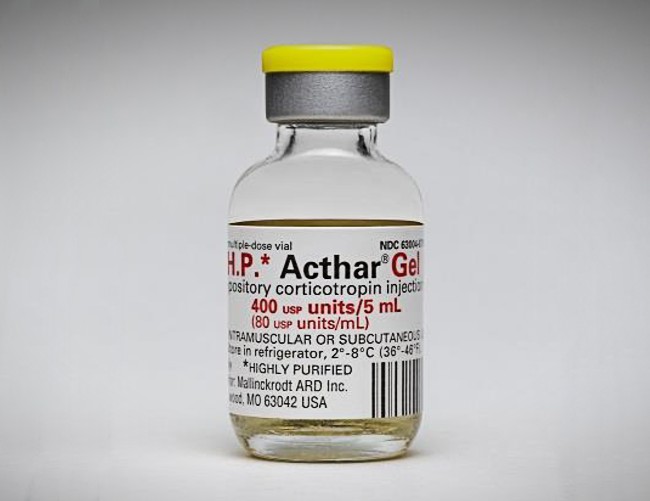

On August 4, as it posted quarterly results, Mallinckrodt, a multi-billion-dollar manufacturer of niche medical products focused on the US market, informed the New York Stock Exchange that it was considering Chapter 11 bankruptcy – the American equivalent of an examinership. In the following week, its stock, already near an all-time low, lost over a third of its value. The company has been facing an avalanche of litigation, compounded by shifts in demand for its drugs and devices targeting rare diseases, pain, disorders of the immune and digestive systems, and respiratory distress. Mallinckrodt’s lawyers are facing an uphill battle, and…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to read the full story?

Unlock this article – and everything else on The Currency – with an annual membership and receive a free Samsonite Upscape suitcase, retailing at €235, delivered to your door.