On September 23 last year, then Taoiseach Leo Varadkar travelled to New York for a UN climate change summit. There, he told delegates – and the hydrocarbon extraction industry listening back home – that new oil drilling had come to an end in Ireland. He said:

“In the last week, on foot of a request from me, our independent Climate Change Advisory Council recommended that exploration for oil should end, as it is incompatible with a low-carbon future. They recommended that exploration for natural gas should continue for now, as a transition fuel that we will need for decades to come while alternatives are developed and fully deployed. I accept this advice and Ireland will now act on it.”

In the Programme for Government (PfG) later agreed in June, Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Green Party agreed to ban new licences for the exploration and extraction of gas as well as oil. The extractives industry was not expecting this further blow.

On the day of Varadkar’s UN speech, Serica Energy, a UK oil and gas company active in the North Sea, abandoned its two frontier exploration licences in the Irish Atlantic. “Irish opportunities have been and are likely to continue to be much longer-term and the expense of maintaining the licences will be redirected to lower-risk, nearer-term opportunities in its core areas elsewhere,” Serica explained at the time.

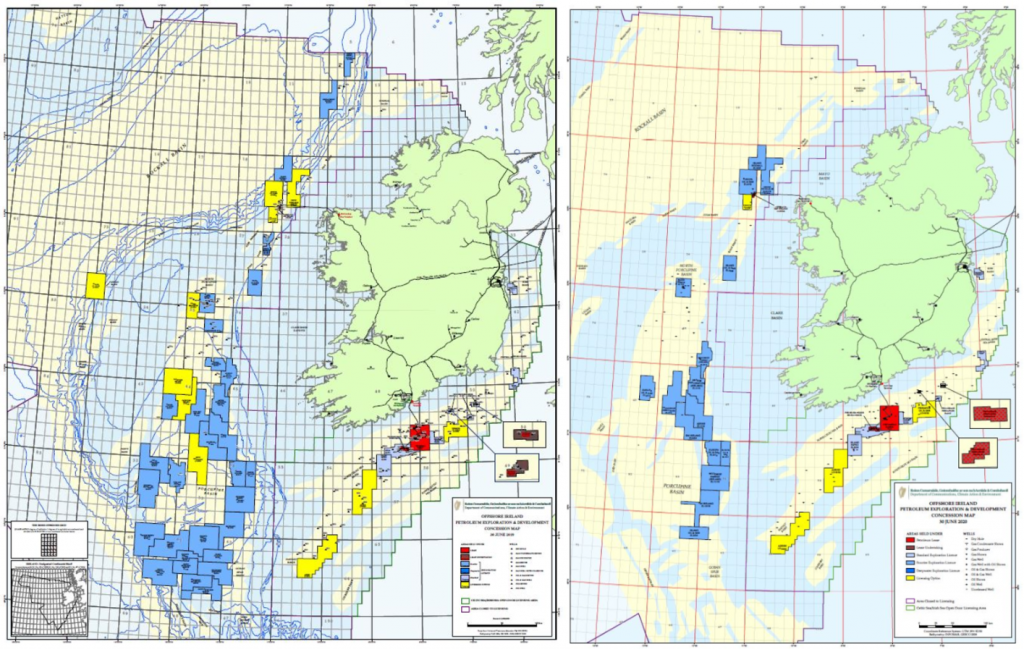

While the company did not specifically reference new Government policy, its move marked the start of a long exodus. New documents from the Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment show that offshore operators have relinquished nearly half of the exploration authorisations active at the time of the UN climate summit.

The briefing papers prepared by Department officials for their new Minister Eamon Ryan in June and published this month show that companies have abandoned five licensing options, which gives them first right to an exploration licence over an offshore area if they confirm interest, while only four remain active. Operators have also relinquished 19 exploration licences giving them the right to actively look for oil and gas in an area, with 23 remaining active.

Regular reports published separately by the Department have so far identified the holders of four of the options and 15 of the licences terminated since September 23. They include a range of international majors, such as US-based ExxonMobil, France’s Total, Norway’s Equinor and China’s CNOOC; domestic players including Petrel and Providence; and a string of other exploration minnows.

Since the oil price crash caused by the Covid-19 pandemic this spring, global hydrocarbon players have been refining further where they target their investment. For many of them, Ireland doesn’t make the cut anymore.

“Ireland has chosen to rely on imported oil and gas”

Petrel Resource’s recently filed 2019 annual accounts detail the reasoning behind its decision to exit two concessions in the Irish Atlantic – and rolls out scathing commentary on national energy policy. The Dublin-based company, which remains locked into a court dispute with majority investors, reported that the decision to abandon an exploration licence and a licencing option was made “reluctantly” and “despite the multiple targets identified”.

Petrel claimed that it had “encouraging” farm-down talks with an unnamed overseas state-owned natural resources company, on the condition of support for the investment in Ireland. “This was available until the Taoiseach’s September 2019 speech to the UN in New York, which received extensive international coverage,” the filing reads, implying that the investor then pulled out and made the licences unviable.

Petrel retains only a 10 per cent interest in an exploration licence held by its Australian partner Woodside Energy – its only asset in Ireland.

Although Varadkar’s decision to stop new oil exploration licences did not affect existing permits such as those relinquished by Petrel, “the reality is that regulatory uncertainties have substantially risen,” Petrel directors commented. They listed a full page of arguments against the policy, ranging from Ireland’s loss of energy independence to the depletion of State revenues on future oil and gas extraction, the higher greenhouse gas emissions of natural gas transported over long distances and the political risks associated with Brexit and energy imports from Russia or the Middle East.

“It is a policy like discouraging consumption of locally-produced red meat and substituting avocados flown in from Mexico – a purely virtue-signalling exercise through which any cattle emissions savings would be cancelled by the extra transport burden,” the filing argues.

Commentary by Petrel chairman John Teeling is strikingly final: “The Irish offshore oil exploration industry despite spending hundreds of millions on grassroot exploration has been stopped in its tracks by political changes and has little or no future,” he wrote in the annual report. Although existing licences were theoretically unaffected by the Government decision, Teeling added: “In reality it is hard to see any more exploration in the Atlantic. Any gas discovery is likely to face years of planning difficulties. The twenty-year debacle over the Corrib gas field was very damaging to Ireland’s reputation. Ireland has chosen to rely on imported oil and gas. The gas ultimately comes from Siberia. It has proven impossible to persuade the authorities that this is unsafe.”

Department reports also reveal that three companies have abandoned petroleum prospecting licences, which gave them the right to search for oil in unlicensed areas. In the most drastic move, Total abandoned both its exploration and prospection licences within three months of Varadkar’s speech. ExxonMobil, too, has now left Ireland entirely.

In briefing papers, the Department’s petroleum affairs division confirms the policy since September 23 has been that any new licences are for natural gas only, excluding oil exploration. However, all applications and authorisations in place before that date are unaffected and still allow their holders to drill for oil. Officials analyse the impact of the changes as follows:

“In the most recent Atlantic margin licensing round held in 2015, an upward swing in interest in the Irish offshore was evident, with a number of large international companies choosing to invest in Ireland for the first time. There is particular interest in exploration close to Corrib, with a number of companies believing further commercial gas finds in the area are likely, which the existing Corrib infrastructure could be used to bring ashore.

“However, the Taoiseach’s announcement of September 2019 and the subsequent publication of new policy principles, industry sentiment has changed significantly. A number of companies have either expressed their intention to or have initiated proceedings to withdraw or surrender licenses and plan to shift investment to other international territories where they believe opportunities are greater.

“In the short term this will mean a reduction in revenue from licenses and lower international confidence in Ireland as a destination for exploration activity. In the longer term, a reduction in exploration activity will reduce further the prospect of additional commercial natural gas finds being made.”

The immediate revenue impact is limited. Exploration companies pay minor fees until they progress to advanced stages of exploration with real commercial potential. The licences abandoned since September contributed a total of less than €1 million annually to the Exchequer.

Concerns around failure to maximise the potential of the Corrib area off the Mayo coast, too, have yet to materialise. None of the authorisations adjacent to the existing gas field have been relinquished. Instead, several have graduated from options to firm licences, including one held by CNOOC. While the Chinese giant has given up its interests in the deep Atlantic, the only exploration permit it has retained is the one in the Corrib area.

Another promising area is off the coast of Barryroe in Co Cork, where Providence is exploring for both oil and gas. It is adjacent to the existing Kinsale gas field and successive wells have found oil. Providence is now in advanced talks with Norwegian-based SpotOn Energy on a farm-out agreement.

Ireland’s security of gas supply, however, is now a serious worry.

*****

A few weeks after Vardkar’s UN speech, industry leaders displayed a sombre mood at their annual Energy Ireland gala dinner last October. Speech after speech drew approval from the black-tied crowd by expressing dismay at the sector being so unloved – and clinging to the hope that the shift to renewable energy will, in fact, boost demand for natural gas for years to come.

Although the Irish Offshore Operators Association (IOOA) is “disappointed” by the extension of the licencing ban to new gas exploration, it is not trying to reverse the policy – instead lobbying to turn remaining existing licences into productive assets. “Our political system needs to wake up to the exposure to our security of supply and our regulators need to be aware of their role in progressing the existing remaining licences,” the IOOA’s chief executive Mandy Johnston told The Currency, claiming that the administration of concessions “has been marred by paralysis for the last number of years”.

“The commitment in the PfG contradicts the previous Government’s assertion that gas will continue to play a vital role in our transition to a lower-carbon society.”

Mandy Johnston, IOOA

Drawing from a policy paper issued last December, Johnston added: “The commitment in the PfG contradicts the previous Government’s assertion that gas will continue to play a vital role in our transition to a lower-carbon society. Moreover, it denies the nation the opportunity to reduce its carbon emissions by using a local supply and it robs the west of Ireland of considerable investment at a time when our country will need it most.” According to IOOA estimates, the Corrib gas field generated €1 billion in investment and 1,000 jobs over ten years for the north-west.

Instead, the new Government’s policy “is committing Ireland to importing all its gas from the UK and elsewhere in the future,” Johnston warned. “Under European law, Ireland must demonstrate that we have taken all the necessary measures so that in the event of disruption we have the capacity to satisfy the demands of society and our economy.”

This point is echoed by Department officials. They wrote in the new minister’s briefing papers:

“Over the coming years, Ireland’s demand for electricity is expected to increase as we electrify heating systems and increase the uptake of electric vehicles. Ireland’s increased demand for electricity, together with the phasing out of peat and coal, will lead to an increase in the amount of natural gas we use in the near term and its importance to the operation and stability of our electricity system.”

With 70 per cent of electricity due to come from renewable sources by 2030, gas-fired power stations that are easy to switch on and off will become crucial to plug the gaps when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine – at least until large-scale energy storage solutions become commercially available.

Meanwhile, Ireland’s Kinsale produced its last gas last month. On a separate note, officials remark that the empty facility is now the focus of a joint project by Equinor and state-owned utility Ervia to capture carbon dioxide emitted by gas-fired power stations and bury it underground.

They add that “natural gas output from the Corrib gas field is passed its peak and will continue to decrease in the coming years”. They forecast that Ireland’s dependence on gas imports will rise from 53 per cent in 2019 to 80 per cent in five years’ time and over 90 per cent in 2030.

With the planned Shannon LNG terminal also officially abandoned in the PfG, the only source of gas imports for the foreseeable future will be the existing pipelines connecting Ireland to Scotland. “There is currently no gas storage in Ireland and no other import routes for natural gas,” the minister has been warned. “In summary, natural gas use in Ireland is seeing increasing demand in the medium term, decreasing indigenous production and increasing dependence on imports from a single source.”

That UK single source happens to be bogged down in frustrating Brexit talks with the EU. Officials welcomed Brussels’ focus in the negotiations on “mechanisms to ensure as far as possible security of supply and efficient trade over interconnectors over different timeframes, taking account of the fact the United Kingdom will leave the internal market in energy”.

They did not say what they thought would happen if this failed.

Offshore turns to wind

While the prospect of erecting oil rigs in Irish waters recedes, Department briefing papers outline the next steps in opening them up to another technology: offshore wind power, the most exciting development in the industry according to KPMG’s global lead for renewables Michael Hayes.

On the one hand, a Marine Planning and Development Management Bill approved by Government before the election is now due to go to the Oireachtas. It would overhaul the existing planning regime for sea areas – currently covering only the foreshore area within 12 nautical miles off the coasts – to allow the construction of offshore wind farms. The new planning regime would also cover international connection infrastructure such as subsea telecommunication cables.

On the other hand, the Department’s international and offshore division has begun work on the terms of conditions to include the technology in the second round of the Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (RESS) next year, to be confirmed if enough projects are ready to compete in it. “The intention is to have a separate auction for offshore wind under the overall RESS framework,” briefing papers state.

The developments are expected to kick-start investment in the sector, as illustrated by the acquisition of a 50 per cent stake in the 1.1GW proposed Codling Bank project off the Wicklow coast by French semi-state utility EDF earlier this year. The stake was sold by Hazel Shore, a vehicle of businessmen Johnny Ronan and his family and Richard Barrett, for an undisclosed amount. The other half of the project is owned by Norwegian marine industries group Fred. Olsen.