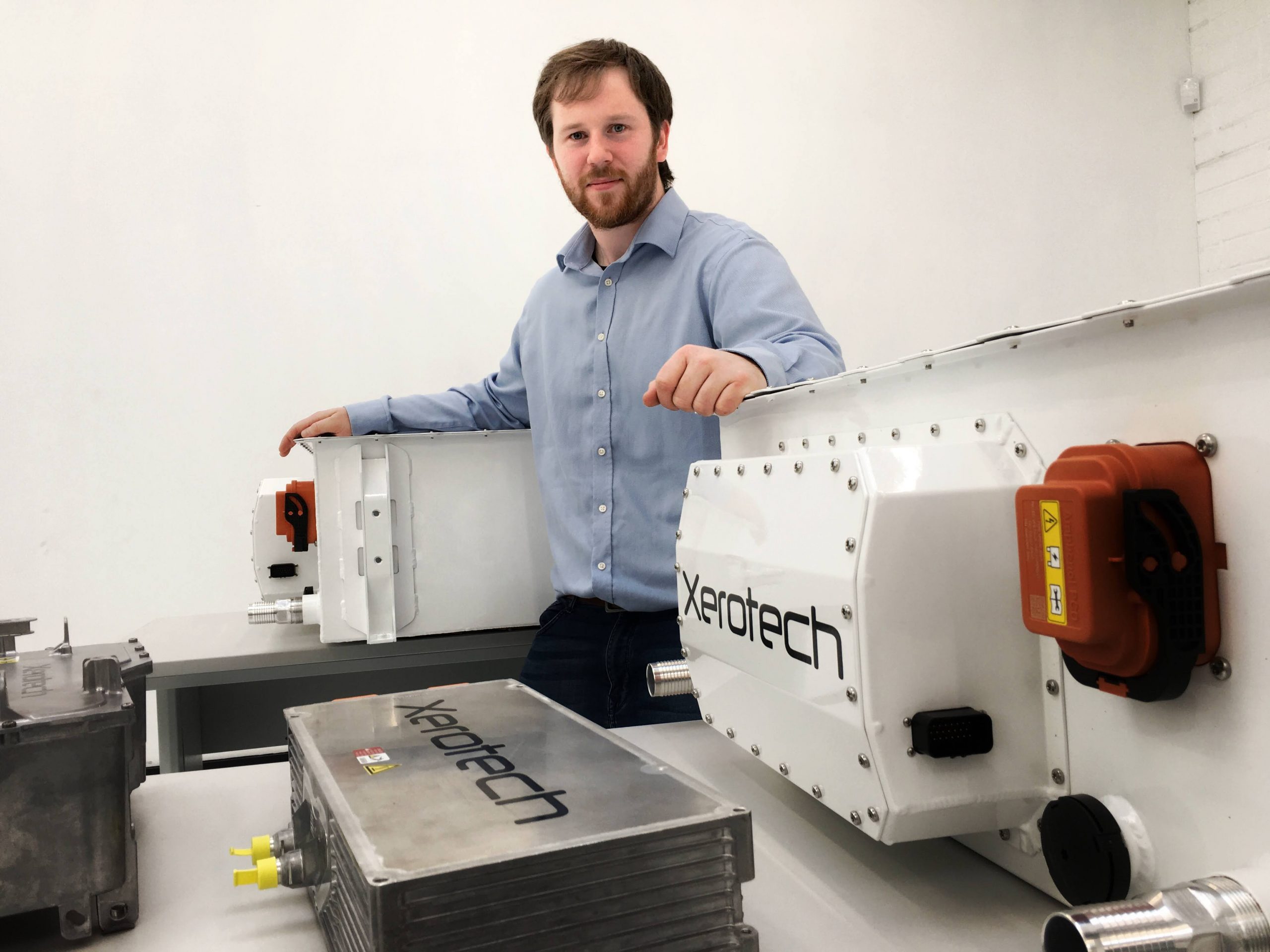

I pull up outside a unit of a newly built business park in Claregalway and take in the view, which extends for miles as far as the famously low-lying fields of Athenry. Livestock are grazing emerald green pastures under stunning blue skies. I then turn around to be swiped into Xerotech’s new headquarters and meet the battery technology company’s founder, 28-year-old Barry Flannery. Within seconds, the bucolic feeling evaporates into a whirlwind of high-tech engineering and unabashed business ambition. We immediately embark on a whistle-stop tour, starting with the battery testing lab – a two-storey structure filled with equipment covered…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to read the full story?

Unlock this article – and everything else on The Currency – with an annual membership and receive a free Samsonite Upscape suitcase, retailing at €235, delivered to your door.