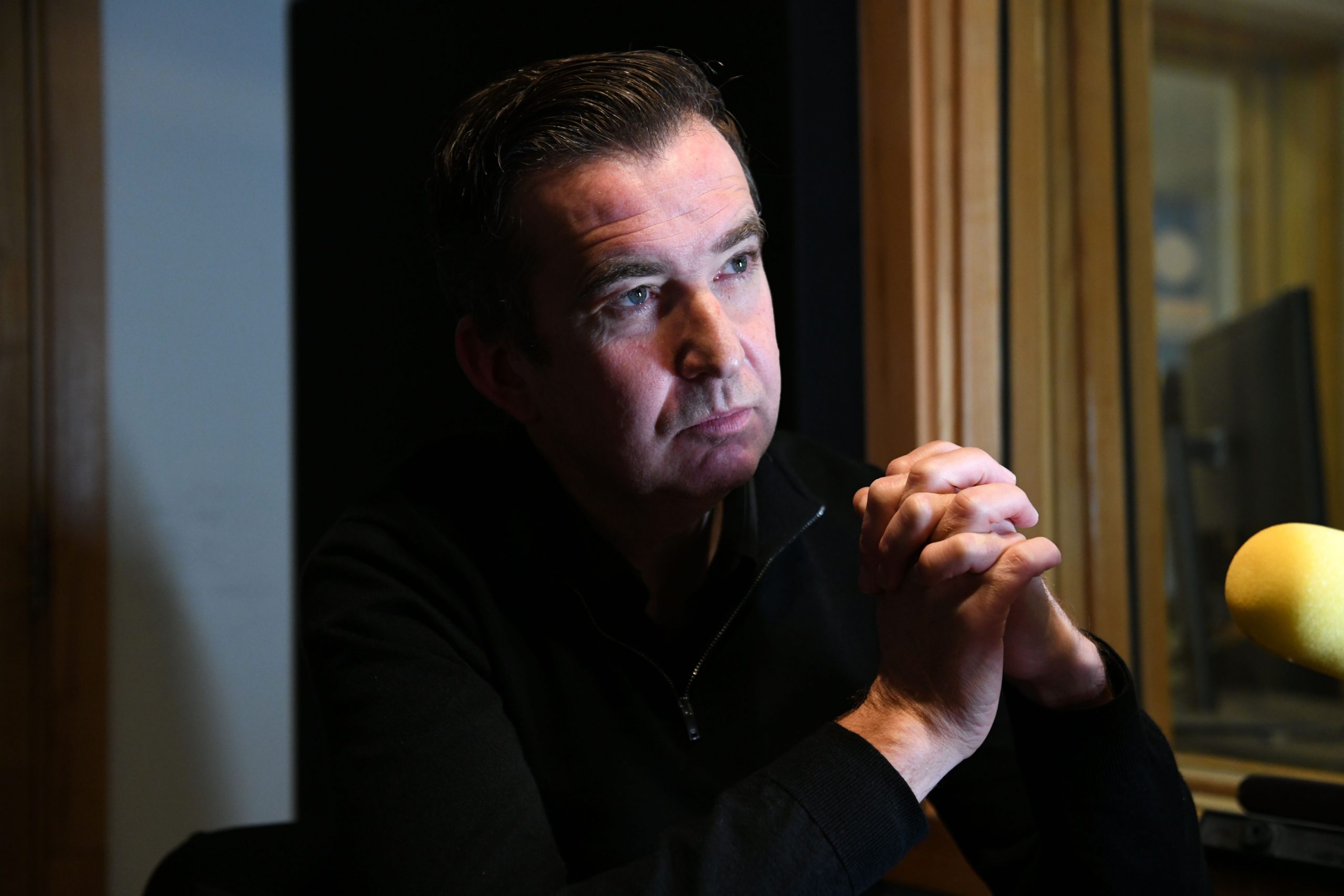

Mark Little has the experience of working both as a journalist and for a social media giant. He used this experience to come up with his first success story Storyful, a social news agency. Now, he is doing it again with Kinzen. Little and Kinzen’s co-founder, Áine Kerr, want to tackle the information crisis which has spread across the Internet with ‘algatorials.’ Little also says that Kinzen could be used anywhere recommendations are made to a customer, meaning entertainment subscriptions could also be on the horizon. He spoke to The Currency about how naïve he was the first time around…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to read the full story?

Unlock this article – and everything else on The Currency – with an annual membership and receive a free Samsonite Upscape suitcase, retailing at €235, delivered to your door.