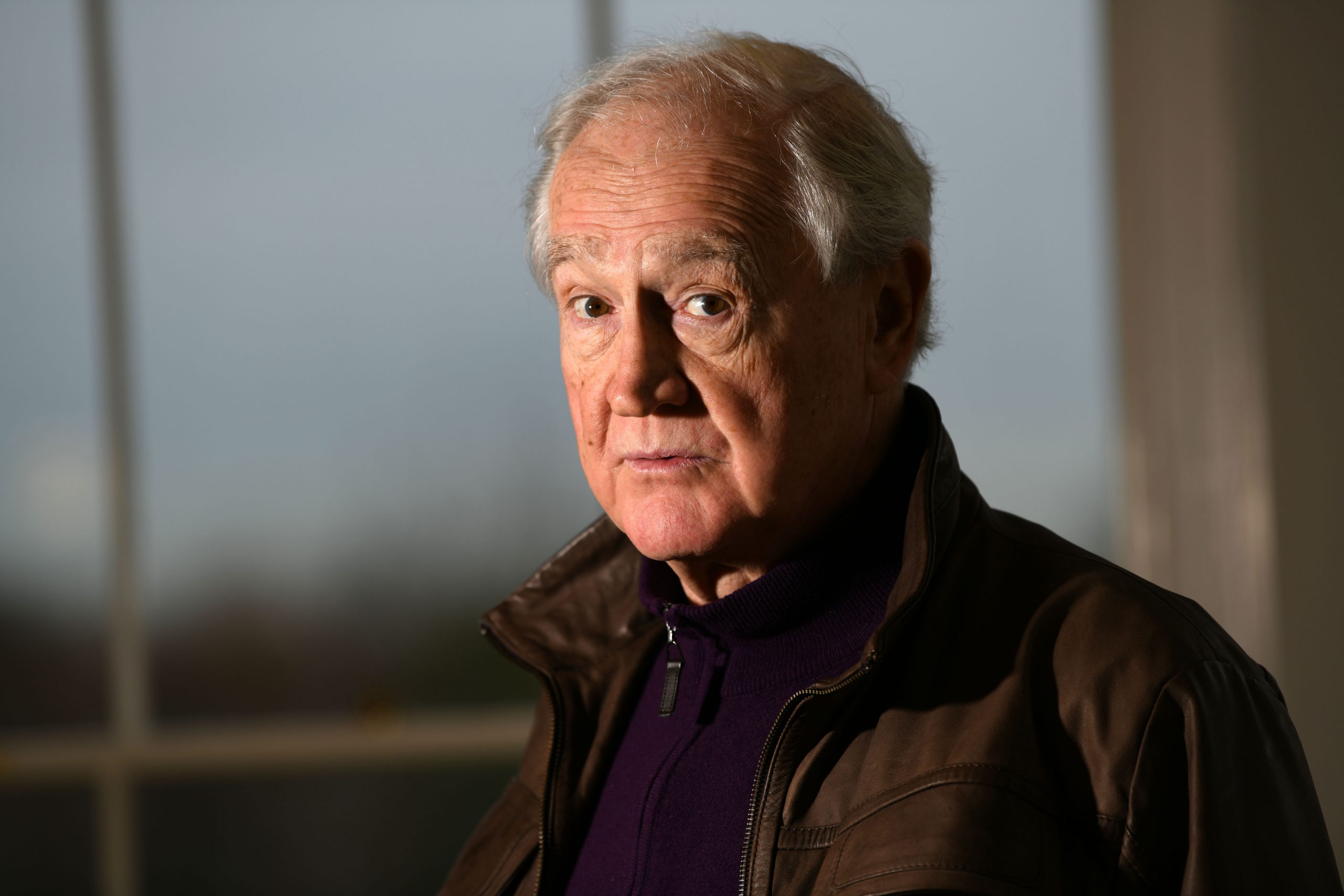

“I’m determined that there will be a supergrid for offshore wind power. There has to be a solution that enables us to decarbonise at scale, and save the planet from overheating. This is something that has driven me since 1989, when I first became aware of the challenge posed by climate change. It will be hard work, but I’ve never baulked at that. It will be done because it has to be done.” Entrepreneur Eddie O’Connor speaks with passion, humour, and conviction – underpinned by a steely resolve – on a two-hour phone call from his office in Nova UCD,…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to read the full story?

Unlock this article – and everything else on The Currency – with an annual membership and receive a free Samsonite Upscape suitcase, retailing at €235, delivered to your door.