At the end of January, an Irish-registered company named Neodrón made headlines when it reached a multi-million dollar settlement with ten multinationals selling any type of electronic equipment with a touch screen. The company had bought existing patents covering the technology and used them to launch infringement actions against tech companies such as Apple, Samsung and Microsoft, essentially threatening to halt the global trade in electronic devices if they didn’t pay compensation.

Neodrón is owned by Realta, the Irish investment vehicle of Magnetar Capital, a US hedge fund firm with $12 billion in assets under management. Magnetar made its name by using collateralised debt obligations to invest aggressively in the belief that the US subprime mortgage market would collapse at the outset of the global financial crisis. It defines its strategy as “targeting white spaces” with “an experimental mentality”, identifying opportunities others haven’t thought of, and which can be repeated along an established pattern.

The Chicago firm is all at once risk-hungry and willing to stick with a proven plan for the long haul; it publicly dismisses the lure of once-off trades. Its critics describe it as a villain and a patent troll. Its partners enjoy Magnetar’s willingness to deploy capital for a decade or more in areas where no one else dares to.

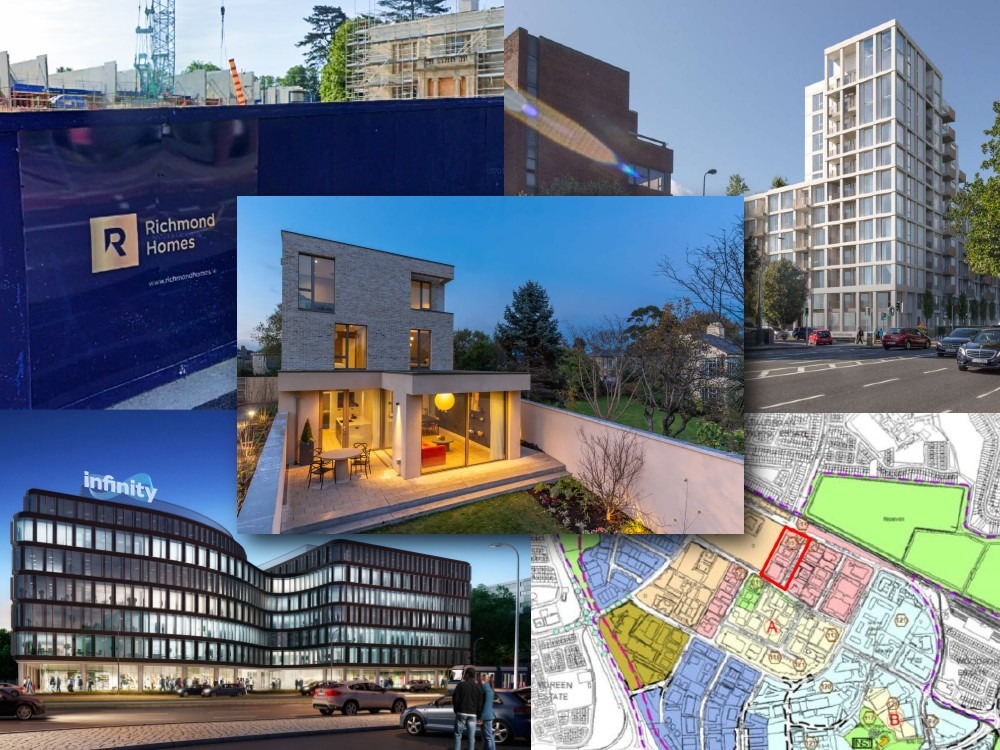

Outside its litigious patent holding subsidiaries, Realta’s investments in Ireland range from car loans and non-bank finance with First Citizen Finance to aviation leasing – and, much more discreetly, the ongoing development of over 1,500 homes, and counting, in and around Dublin in the past four years.

Its partner in the Irish property market is Avestus Capital Partners. The two firms share a preference for working under the radar. Much like Magnetar, Avestus pops up in headlines when an individual deal catches brief media attention. There has, however, never been an attempt to document its full portfolio, its business model and its performance – until now.

*****

Reams of coverage have been dedicated to the legacy issues that occupied the first four years of Avestus’s existence. After Celtic Tiger dealmaker Derek Quinlan left his overleveraged firm Quinlan Private in the wake of the crash and moved to Switzerland to deal with his personal debt, his minority partners Olan Cremin, Thomas Dowd, Peter Donnelly and Mark O’Donnell stayed behind. They formed Avestus Capital Partners in 2010 while collaborating with Nama to work through the corporate side of the Quinlan Private wreckage, recovering funds for a number of investors.

The new firm was part of a holding structure, Avestus Nominees, which overlaps with the old Quinlan Private and has continued to hold some legacy entities as they wound down. They performed regulatory obligations during the years following the disposal of debts and properties. This is coming to an end, with only one Quinlan-era development in Slovakia remaining active. Avestus Nominees also retains a 39 per cent holding in parking management group Tazbell, the parent company of Parkrite and Dublin Street Parking Services, having sold its majority stake in 2018.

The trials and tribulations associated with this process have been well documented – including on The Currency last year when the Comptroller and Auditor General scrutinised the 2012 sale of Nama’s Nantes portfolio to Clairvue, a Californian investment firm backed by Goldman Sachs.

This article is not a repeat of that boom-and-bust hubris narrative, but rather about what happened next: how Cremin, Dowd, O’Donnell and Peter Donnelly, joined by Matthew Brennan, Fergus Farrell and Mark Donnelly (no relation), have grown a pipeline of new projects in the past six years; the investors they have contracted as far as Los Angeles to raise over €1 billion in capital; how their role alongside these investors grew from advisors to joint venture partners; the 4,000 homes they have bought, sold or secured planning and funding for in Ireland in the past six years, over 300 of which they have actually built; and the interests they have built upon their previous experience in commercial property, including in eastern Europe.

Avestus’s seven directors have a policy never to give interviews. However, their story is told by corporate filings from over 70 related companies in ten countries; Government property databases and real estate agents’ reports; and information confirmed to The Currency by sources familiar with the firm’s transactions.

From the very start, the firm engaged into the twin tracks of new developments and institutional rental property ownership.

Avestus really started its independent life in 2014. At the end of its recovery work, the firm pulled off two profitable deals which would help it generate its own capital to invest in future business:

- One was the purchase of two eastern European assets (33 per cent of the Explora office building in the Czech capital Prague and 50 per cent of the Mall of Plovdiv shopping centre in Bulgaria) from GE Capital, which was exiting the property business. Avestus later sold its interest in the Explora building at a profit in 2018.

- The other was a transaction with the liquidators of IBRC allowing the sale of a former Quinlan Private portfolio including the Heuston South Quarter office complex, home to eir’s headquarters in Dublin; the Four Seasons hotel in Prague; and the Diagonal Mar shopping centre in Barcelona. The buyer, US specialist commercial property investment firm Northwood, engaged Avestus as asset manager for the properties.

From the very start, Avestus engaged in the twin tracks of new developments and institutional rental property ownership. Development came first – albeit in a changed world. Gone were the boom-time traditions of easy-flowing bank credit, handshake deals and personal guarantees. In facts, Irish banks have almost disappeared from Avestus’s roll of backers. None of the firm’s 19 developments to date was initially funded by a bank. The first four were refinanced by Ulster Bank after planning permission was secured. Since then, Avestus has only once made similar deals with each of Bank of Ireland and AIB.

Instead, its leverage finance now comes from so-called shadow banks – specialist lenders outside the traditional banking sector, in this case Activate in Ireland and GreenOak in the UK. This is not necessarily by choice, as this type of finance is more expensive than bank debt. While Avestus reported borrowing from Ulster Bank at 4 per cent, GreenOak charges 8 per cent interest plus once-off arrangement and exit fees of 2 per cent each. Activate’s interest rate is 7 per cent in addition to in- and out-fees of between 1 and 1.5 per cent each.

When it comes to the risk taken right from the early stages of property development – buying a site, designing a project and taking it through the planning maze – some developers like Cairn or Glenveagh have gone down the PLC route to raise funds from stock market investors. Others, like Johnny Ronan and Avestus, have formed partnerships with private equity funds. And this can take them a lot further away than London.

Click on locations below for details of Avestus developments or jump to the section detailing the story behind each site.

Avestus inherited a past US connection under the form of the Quinlan Private European Strategic Fund, an American vehicle that still appears in the group’s filings as a mostly impaired asset. Instead of running their own investment fund in America, the new firm began to advise large private equity houses there – first Northwood Investors as described above, and Marathon Asset Management for landlord-type investments as we will see below. With its own funds becoming available, however, the Irish firm wanted more lucrative co-investment opportunities.

Avestus’s first funding deal was with Wall Street private equity firm Centerbridge Partners. The US investor advanced €47.8 million, with Avestus putting in €3.2 million – or 6 per cent of the partnership’s total pot. With this €51 million, they bought three Dublin suburban sites in 2014 at Hollywoodrath on the northern outskirts of the city; Scholarstown in Rathfarnham; and across the street from Portmarnock train station. Under the deal, the nitty-gritty of development and construction was taken on by industry veterans Aodon Bourke – a former director of developer Sean Dunne’s companies – and property finance specialist Patricia Hinch, previously of GE Woodchester Capital.

Both Avestus and the Bourke-Hinch pair formed companies named Regency, the brand used to bring the homes to market. They formed joint ventures for each project which were 95 per cent owned by Centerbridge, 4.75 per cent by Avestus and 0.25 per cent by Bourke and Hinchh. They then borrowed over €30 million from Ulster Bank to start building, and sold 118 houses between Hollywoodrath and Scholarstown by July 27, 2017. On that day, however, the three-way partnership came to an end when Centerbridge sold its interest in the three projects to another US private equity house, Bain Capital.

The sale did not appear to generate a direct return on the equity Avestus had placed in the projects. Its investments in the joint ventures were under the form of interest-free loans, and the Bain transaction covered the negative equity accumulated by Avestus in early development phases, but not more. The firm did, however, collect €2.5 million in management and development fees from the three projects.

Bourke and Hinch continued to develop the sites for Bain under the Regency brand, while Avestus renamed its on-the-ground development subsidiary Richmond Homes. We will see them return to both Scholarstown and Portmarnock later. As for funding, they were already looking elsewhere.

Since November 2016, Avestus had begun to build a second pipeline of projects – this time with Magnetar. Their Dawson Place development of 25 houses on an infill site in Dublin 7 was the first of 13 similar investments with the US hedge fund and they have built or committed to a total 1,552 homes to date. All sites are in the greater Dublin area except one housing estate in Ardee, Co Louth.

Two of the first Magnetar vehicles were named after Brodir and Ospak, Viking brothers who fought at the battle of Clontarf.

Each joint venture between Avestus and Magnetar takes the form of a partnership between two companies: one owned by Avestus, which provides 10 per cent of upfront funding under the form of interest-free loans; and one formally controlled by Avestus through a 50.25 per cent shareholding, but in fact used to channel Magnetar’s 90 per cent funding for the project. As of their last accounts published to the end of 2018, these joint ventures had raised €60 million from the US funds’s Irish unit, Realta, of which €5.7 million was already refinanced or paid back.

The first two Magnetar vehicles were named after Brodir and Ospak, Viking brothers who fought at the battle of Clontarf – a street adjacent to their first project is named after Brodir, and their second one was in Clontarf. Since then, the two partners have simplified their subsidiaries’ naming convention: Those carrying Avestus investment start with an A, and Magnetar’s start with an M. This is not over as they registered another pair of such companies last year, which is not yet linked to any property – but ready to act upon any opportunity that may arise.

Click on the image below to navigate the corporate map.

From financial adviser to house builder

As its pipeline grew, Avestus found it difficult to secure building contractors amid the skills crunch that emerged from the departure of migrant workers after the crash and the construction recovery in recent years. In 2018, it formed its own building subsidiary, Arkmount Construction, which has been active on Magnetar-funded sites in Ardee, Sandymount and Baldoyle and is lined up for similar jobs in Rush and Malahide later this year. Arkmount is understood to focus on traditional detached or semi-detached housing designs to speed up delivery of projects where contractor capacity is hard to come by, rather than as a commercial venture in itself.

While the Magnetar partnership initially focused on smaller developments, Avestus teamed up with another pugnacious US hedge fund manager better known in Ireland for its vulture fund activity – Cerberus. In this case, as revealed by The Currency last year, the opportunity was to take over and complete Streamstown Lane, the undeveloped portion of a high-end housing estate started by Donal Caulfield and Leo Meenagh before the financial crisis in Malahide, Co Dublin. Cerberus took a larger share of the funding than Avestus’s other partners, pouring €5.4 million into the joint venture across equity and intercompany loans as of December 2019 and leaving the Dublin developer with just a 2.5 per cent stake in initial funding.

A second, short-lived joint venture with Cerberus called Seaview was, as its name and 2019 timing suggest, understood to be lined up for the much larger Bay View development on the coastal site of the former Baldoyle racecourse. However, Cerberus did not follow through with the investment and Avestus returned to its other American partners to develop bigger projects.

For its largest development to date, the 564-apartment Sandyford Central in towering 17-story blocks on a former warehouse site previously owned by a vehicle of John Fleming, Avestus brought in another capital partner. Los Angeles-based alternative investment manager Ares provided the funds needed for the €45 million site purchase in 2019.

While Sandyford Central was the first construction development bringing together Avestus and Ares, they had already been co-investing in Irish property for several years as commercial landlords. This is the other face of the Ballsbridge firm’s business.

Avestus the institutional landlord: less office space, more PRS

A Marathon through the XVI portfolio

In 2014, while Centerbridge was funding Avestus’s first construction projects in Ireland, another hedge fund manager a few blocks away in mid-town Manhattan struck an investment deal with the Irish property firm. Marathon describes its sector strategy as follows:

“Marathon’s European Real Estate platform engages primarily in the purchase of value-add commercial real estate and in special situations, including non-performing loans that allow Marathon to take possession of properties at a discount to market value.”

Bryant Park ICAV, the Irish vehicle named after Marathon’s New York address, targeted rental apartment blocks in Dublin, starting with individual building purchases in late 2014 and early 2015.

Then in the spring of that year, Marathon’s appetite for “special situations” showed through when the joint venture made a successful bid for the best part of Nama’s Project Plum – though not the entire residential portfolio of 588 apartments, as incorrectly reported at the time.

Agents Savills later revealed that the deal covered around 475 of the most attractive properties for €95.8 million, leaving out older buildings such as the one at Lad Lane in Dublin 2. This was instead sold to Iput, which has now demolished it and is redeveloping the site as part of its Wilton Park scheme.

Avestus and Marathon continued to add to their apartment bank. In June 2016, they closed investment with Bryant Park, having spent €150 million on 815 apartments across 16 sites, all in Dublin except one in Cork.

In June, I•RES acquired the entire portfolio for €285 million and reported that it was 98 per cent leased, generating €14.2 million in gross annual rent.

Green Liffey: the Ares JV

In 2015, Ares opened its fifth European Real Estate Fund to investors. The Californian fund channelled €1.8 billion into property across the EU over the following five years. In Ireland, this took the form of a partnership with Avestus to purchase office space in Dublin.

Their joint venture, Green Liffey, was named after the sale of Nama’s Liffey portfolio in which it successfully bid for three properties. This led to the May 2016 acquisition of Heineken’s Irish headquarters at One Kilmainham Square, along with a pair of connecting office blocks on Pearse St and Magennis Court. Although the sale price of these individual properties was not disclosed, reports of Nama’s overall Liffey transaction suggest Avestus and Ares paid around €40 million for them.

In 2017, the joint venture went back to the market and purchased Classon House in Dundrum from Green Reit for €20.4 million, followed by block P2 of Eastpoint Business Park for €12 million. In September that year, the final acquisition of blocks 4 and 5 of the Harcourt Centre in the south city centre for €47 million brought the total invested with Ares to €120 million.

Less than two years later, the joint venture began to cash in on increasing office property values, selling Pearse St and Magennis Court for €27.2 million mid-2019. By Christmas that year, French institutional landlord Corum reported having paid a combined €68.2 million for One Kilmainham Square and Classon House. The Harcourt Centre was Avestus and Ares’s latest disposal in early 2020, fetching €54 million from Arena Invest.

Avestus’s joint venture with Ares was left with the East Point building only when Covid-19 froze the office market one year ago and their plans are unclear for this asset – the smallest investment in their portfolio.

Click on each location for details of Avestus’s current rental investments.

Herbert Park and Havitat

In July 2018, Avestus announced that it was launching a new Irish Residential PRS Fund, operating under the ICAV vehicle Herbert Park named after its address in Ballsbridge. “The Fund has up to €290 million to invest and is supported by Nordic and German institutional investors, as well as the Ireland Strategic Investment Fund (ISIF),” the firm said. The latest accounts for ISIF to the end of 2019 showed that it had released €2.95 million in value out of its €25 million commitment to the fund.

Armed with this initial funding, Herbert Park first acquired two blocks of around 45 apartments each: Abbey Glen in Cabinteely, purchased from Cork developers O’Callaghan Properties for €14.8 million, and Wolfe Tone Lofts in Dublin’s north city centre, sold by the McGarell Reilly group for €22 million.

Avestus then went back to Scholarstown and Station Manor, the two suburban developments it had started in 2014 with Centerbridge before selling them prior to completion to Bain Capital. Herbert Park acquired apartment blocks in both properties, totalling 95 units, for €42 million.

This was just a warm-up. At the end of 2019, the firm secured its largest acquisition to date, winning the Project Vert portfolio of two complexes totalling 385 apartments, Elmfield in Leopardstown and Neptune in Dún Laoghaire. The deal was worth €216.1 million to the sellers, London investment firm Tristan Capital Partners and its Irish minority operator SW3 Capital.

The sellers advertised Project Vert as collecting a total of €9.4 million in annual rent, with a gap to market rents estimated to be just under €1 million. The sale price therefore accounted for a 4.35 per cent yield, with the potential to push this to 4.8 per cent through rent increases. The void rate was 2.04 per cent at Elmfield in 2019 and only 0.56 per cent at Neptune. The vast majority of tenants were foreign residents, many working for the surrounding multinationals – an astonishing 86 per cent at Elmfield.

Also in 2019, when Avestus the developer completed its Belvoir development in south Dublin, it found that the best buyer for it was none other than Avestus the institutional landlord. The apartment scheme transferred seamlessly into Herbert Park.

Since then, the fund has continued to acquire rental properties on both sides of the Liffey: 40 apartments over the redeveloped Swan leisure centre in Rathmines from project contractor John Paul Construction in early 2020; the forward sale of 110 apartments on the site of the former Swiss Cottage pub in Santry from MB McNamara, which has just closed in recent days; and another forward sale at Davitt Road, where Herbert Park is committed to purchasing the 265 apartments under development by Brian M Durkan on the site of the former Dulux factory for €127 million when Covid-19 allows their completion later this year. According to estate agents, the net initial yield for this complex is expected to be 3.8 per cent.

When this happens, Herbert Park will own more than 1,000 apartments, having spent over €500 million. Avestus recently formed a dedicated property management and letting subsidiary, Havitat, which centralises the leasing and servicing of the fund’s properties.

Avestus the eastern European investor: office blocks and residential parks from Poland to Prague

In addition to its Irish portfolio, a subsidiary of the firm called Avestus Real Estate is dedicated to investments in central and eastern Europe. Avestus’s only overseas asset left over from the Quinlan Private era is South City, a €120 million mixed-use development with 4,000 homes as well as office space and a shopping centre. The greenfield site is located outside Bratislava, where Slovakia’s border meets those of Austria and Hungary along the Danube river. After years of planning delays, local developer Cresco is now building out the project in phases.

Initially in a 50-50 joint venture with Cresco, Avestus has now reduced its stake to 35.6 per cent, indicative of a potential exit in the near future. Accounts filed by an Avestus vehicle in Luxembourg show it was owed €14 million by the project at the end of 2019.

The heart of Avestus’s interests in the region, however, beats further north, in Poland. There, it has teamed up with Tristan Capital in two successive joint ventures – one started in 2015 to develop Enterprise Park, a 61,420sqm office complex now complete and leased in Krakow; and another in Wroclaw called Infinity, where 22,000sqm of office space are under construction.

Still in Poland, Avestus completed a 17,200sqm city-centre office and retail building in Lodz called Imagine – this time channelling investment from a Cyprus-registered partner, Lanel Holdings. Filings show that Lanel is a vehicle for a number of private individuals including members of the Shohet family, whose Swiss-based family office has a history of investment alongside the Irish firm in eastern Europe.

The three commercial properties are destined to be sold in the near future, with guide prices estimated at €35 million for Imagine, €40 million for Enterprise Park and €55 million for Infinity.

Also funded by Lanel, Avestus has been developing Modřanský Háj, a residential development outside the Czech capital Prague where nearly all of the 425 units – apartments, houses and sites – have now been sold.

Still sifting through the debris of the crash

On January 28 last, a ruling by High Court Judge Brian O’Moore cleared a minor point in a case involving Avestus Capital Partners, Stapleford Finance Ltd and Capital Trustee Services Ltd. It illustrates the kind of intricacies Avestus has been dealing with since the collapse of Quinlan Private.

According to Justice O’Moore, Capita represents the interests of its client Peter Lavelle and his family, who had invested in the Mall of Sofia in Bulgaria and the Galeria Kazimierz, another shopping centre in Poland. The investments were initially made through Quinlan Private and Avestus distributed the proceeds from their sale in 2014 and 2018.

In the meantime, however, it emerged that Lavelle had secured borrowings from Anglo Irish Bank over his investment in the eastern European shopping centres. The Anglo debt was later purchased by Stapleford, an Irish vehicle of US vulture fund CarVal, which in turn appointed two successive servicing firms to pursue borrowers – first Pepper Finance, and later Everyday Finance.

Avestus found itself holding “proceeds from two investments in respect of which competing claims have been made” and ended up dragging the respective agents of CarVal and Lavelle to the High Court to find out who should receive the distribution.

The case has been going on for more than five years and shows no sign of nearing a resolution – the recent interim ruling was only to allow Everyday to replace Stapleford in proceedings.

Returns, hurdles and profit shares

While it is difficult to keep financial track of Avestus’s eastern European business, figures available for the firm’s more significant Irish investments can help us assess its performance. The first development it brought to completion, Dawson Place, shows a strong gross margin: with nearly all houses sold during 2018, proceeds achieved a 50 per cent return on the total funding raised from Avestus, its partner Magnetar and Ulster Bank. Of this nearly €10 million surplus, company accounts show that about half was pre-empted by Magnetar under the form of intercompany interest; over €640,000 in fees was paid to Avestus’s subsidiary Richmond Homes; and bank interest absorbed around a quarter of a million. This leaves over €3 million, subject to taxes and fees, to be shared between Avestus and Magnetar.

Similarly, the sale of the Belvoir apartment block to Avestus’ own PRS fund for €28 million would leave a 43 per cent gross return, worth over €8 million, over the €20 million in capital raised. Again, nearly half of this is earmarked for Magnetar through intercompany loan interest, leaving €4 million or so to share after bank interest and other costs. Richmond Homes also collected over €340,000 in fees.

By contrast, the last development with near-complete sales data, Ashfield Place in Templeogue, appears to have generated a smaller margin. With all 16 houses slated to sell for a total of €10 million, a gross margin of 30 per cent is on the cards. Final accounts have yet to show how this played out, but it seems the share of profit reserved for Magnetar through intercompany interest may be higher in this case.

These examples show how Avestus fares in the two steps of the funding mix crucial to the success of a development project:

- The amount of debt and the costs involved. “In any development transaction, you’d have around 30-35 per cent equity and 65-70 per cent debt. You can go higher but the debt becomes more expensive,” explains Conor Larkin, director of corporate finance advisory firm LeBruin. “There’s a balance at which it makes sense. Avestus typically goes for conservative leverage and brings in more institutional equity, although recently development funding pricing has gone up as a result of the pandemic.”

- The profit-sharing agreement with the capital partner in each joint venture, which Larkin explains is usually defined by “hurdles” or levels of return above which the developer’s share increases. “The main point of hurdles is to start as low as possible and that’s what we would advise our clients to negotiate. Your share of returns kicks in earlier.

The lowest is usually between 10 and 12 per cent,” says Larkin, adding that there are typically two or three hurdles in any given PRS project. Up to 10 per cent return the profit share may look like 80/20, then 70/30 from 12.5 per cent and 60/40 from 15 per cent depending on the level of co-invest on day one. By chipping in up to one in ten euros in each project, Avestus is in a better position for such negotiations than a developer with little skin in the game.

These agreements are undisclosed, but the obligations contracted under intercompany loans provided by Magnetar and Ares give an idea of the minimum they expect. “There’s a minimum return that most private equity houses would target. Any amount committed in the accounts is equivalent to this minimum return or slightly higher,” says Larkin. Magnetar loaned funds into its projects at 17 to 18.75 per cent interest, plus 3.5 per cent combined once-off arrangement and exit fees. Meanwhile, Ares lent €46 million to the Sandyford Central development at 15.5 per cent interest. Tax may also play a role in the share of profit an investor chooses to extract under the form of interest.

On the investment side, give or take discrepancies in the inclusion of taxes and fees, the XVI residential portfolio assembled with Marathon for €150 million by 2016 had nearly doubled in value by the time it was sold three years later. The Ares joint venture made a 25 per cent gain on its €120 million office acquisitions, holding onto assets for less than three years on average – and it is left with one building to spare. Together, these two partnerships have generated €136 million in capital gains since 2014, not to mention rent collections. The profit share between Avestus and the two US investors is undisclosed.

The Herbert Park PRS portfolio, meanwhile, has yet to prove its worth. It is still being assembled, at considerably higher prices than its Marathon predecessor. The long-term approach of its pension fund-type European investors and Avestus’s investment in the Havitat property management business suggest that this is less of a quick coup and more of a long bet on Dublin’s housing needs.

When it comes to the bottom line, Avestus companies file only abridged financial statements without a full profit and loss account. The firm’s central entity Avestus Capital Partners Ltd, however, shows in its latest filing to the end of 2018 that it made a €6.5 million profit that year, up from €1.4 million in 2017. It also dipped into €32 million in accumulated profits to pay a €15.7 million dividend, which was cashed out through an equivalent capital reduction by its immediate parent. Its seven directors, meanwhile, were each paid an annual average of €217,000. There are no other investors reported in Avestus’s ownership structure.

The seven men behind Avestus have generated these healthy figures through their ability to bring in hard-nosed American hedge fund investors on workable terms; a portfolio of Dublin central and suburban sites across development and residential investment projects, many of them infill opportunities chosen for their strong public transport connections and a sense for the locations where citizens and planners increasingly want to see homes; and a flair for good discounts, illustrated by the number of acquisitions they have made from Nama and receivers – having been through this mill themselves before.

They were also lucky to get out of their investments in office space just in time to avoid the Covid-19 hit. Instead, they have been making the best of new build-to-rent planning guidelines for apartments allowing higher density and fewer costly obligations such as basements and car parks, as long as the properties provide shared amenities like gyms and remain owned and managed by institutional landlords for at least 15 years.

The future of Avestus’ ongoing developments, and that of their Herbert Park/Havitat landlord venture, now depends on the pandemic’s knock-on effect on the private rented residential sector. We know Ireland still needs thousands of homes, but will the demand for urban apartments be as high as expected – and, crucially for the firm and its investors, will this be at the rent levels observed until now?

Site by site: 3,000 new homes from Dublin to Ardee

Hollywoodrath

The greenfield Hollywoodrath site in Hollystown, north Co Dublin was the first significant development project of the new Avestus, and the first of three acquired with Regency and the US investment fund Centerbridge.

On March 21, 2014, the three partners bought the property from receivers appointed by Ulster Bank to developers Donal Caulfield and Leo Meenagh’s company Garbo Developments. They paid €14.1 million for the site still in agricultural use, financed through intercompany loans nearly entirely provided by Centerbridge. Garbo had obtained planning permission for 331 houses there in 2008, but the financial crisis hit before any had a chance to come out of the ground.

The new owners made use of an update to the local development plan to re-apply and secure final permission for 435 houses by June 2015. In October that year, they formalised plans to build out the site through a joint venture called Gembira owned at 95 per cent by Centerbridge, 4.75 per cent by Avestus and 0.25 per cent by Regency.

They borrowed €9.8 million from Ulster Bank at a rate of Euribor (i.e. zero) plus 4 per cent to repay around €5.5 million of their outlay for the site purchase and begin construction. The first house was sold in April 2016 and the Residential Property Price Register shows that 82 more had found buyers by the end of July 2017, generating €23.6 million in revenue. These sales covered the funds advanced by the investors and their bank up to that point.

Then on July 27, 2017, Centerbridge closed the sale of its interest in the three developments to Bain Capital. The joint venture repaid Avestus for the €1 million in negative equity shown on the balance sheet of its vehicle for Hollywoodrath at the end of 2016. As the funds advanced by Avestus were interest-free, its income from the project came under the form of fees charged by Avestus Capital Partners and its Richmond subsidiary to manage the project.

These came to nearly €800,000 as reported in the joint venture’s accounts from 2014 to the end of 2016. This figure may have been topped up with further payments in the first seven months of 2017, indicating that Avestus more than doubled its initial investment of €759,726 despite the apparent lack of equity return.

Scholarstown Wood

When Nama took over the loans owed to AIB, Bank of Ireland and Anglo by developer Michael Whelan’s company Maplewood Developments, one of the underlying properties was a site with planning permission for 337 residential units at Scholarstown Road in the south Dublin suburb of Rathfarnham.

One of the first jobs for Michael Coyle and Simon Simon Davidson, the HWBC Allsop receivers appointed to Maplewood by Nama, was to apply for an extension before permission ran out. The local authority, however, argued that planning guidelines had changed and rejected the application.

Enter Broadcrest, another joint venture between Avestus, Centerbridge and Regency. On August 5, 2014, the company paid €37.9 million for the property, mostly funded by a €36.3 million, 3.8 per cent loan from Centerbridge. Avestus, meanwhile, advanced €1.9 million interest-free to its vehicle for the project. Smaller injections from Centerbridge continued as the project progressed.

The following year, Broadcrest secured planning permission for 247 houses and 70 apartments. Then in 2016, the joint venture secured a €29.8 million credit facility from Ulster Bank at Euribor rates plus four per cent, and drew down €23.8 million to build out the site. This partly refinanced the partners’ advances and allowed construction to start, leaving a net funding pot of €50 million.

The development got off to a roaring launch when the first house sold for half a million in December 2016. By the time Bain Capital bought out the joint venture in July 2017, it had sold 35 houses for nearly €16 million, according to the Residential Property Price Register.

Bain’s payout covered outstanding liabilities, including repayment of Ulster Bank’s loans and amounts advanced by Avestus, who walked away with the €1.3 million in fees paid to Avestus Capital Partners and Richmond since the start of the project.

The development’s new owners continued to sell houses as they reached completion – but not the apartments. Instead, they recently sold a multi-unit block on the site back to Avestus’s PRS fund, which will rent it out under its new Havitat brand alongside a similar deal at Station Manor below.

Station Manor

The third joint venture between Avestus, Centerbridge and Regency, called Circleside, bought a site opposite Portmarnock train station from a private individual for €10.2 million on November 20, 2014.

Circleside applied for planning permission to demolish an existing house and build 65 houses and a block of 56 apartments instead. It took until the end of May 2016 for an appeal to An Bord Pleanála to be withdrawn and the development to get the green light with a reduced number of 61 houses and 51 apartments.

Construction did not start until early 2017, and there is no record of the joint venture raising bank debt for the Station Manor development. Instead, the entire joint venture was sold to Bain Capital in July 2017 before additional finance was sought. Avestus and Richmond had collected €340,000 in fees from the development before the sale. Bain and its lenders put in the financial heavy lifting behind the development phase before completed houses started to sell in 2018.

None of the planned apartments, however, have gone on sale. Instead, Avestus went back to Station Manor to buy back the finished block as a landlord investor with its Herbert Park vehicle. Havitat is now listing the complex’s one- and two-bedroom apartment as “launching in 2021”.

Dawson Place

On November 8, 2016, Magnetar’s Irish subsidiary Realta released funds to a joint venture with Aventus for the first time. It loaned €3.3 million to Brodir Connect DAC at an interest rate of 17 per cent and topped this up with another €343,800 the following June. The vehicle also borrowed €2.4 million from Ulster Bank.

The company acquired a site in Dublin’s Arbour Hill with planning permission for 25 townhouses and valued its “stocks” comprising the land and any ongoing works at €6.5 million at the end of 2017. For its part, Avestus invested €400,000 in the partnership through its 100 per cent owned vehicle Provost Spire DAC and borrowed €265,219 from the bank. Its share of the site value was booked at €643,644, valuing the entire property at over €7 million one year after its purchase.

The development is now sold out and all loans were repaid in 2018. The Residential Property Price register shows that 18 houses sold that year for an average price of €426,000, while two others were purchased below market price just under €100,000 (presumably in compliance with social housing requirements).

Assuming the remaining units fetched a similar average market price, sales totalled around €10 million, returning a 50 per cent margin over the funds injected by the investors and the bank into the project. The terms of intercompany debt agreed with Realta suggest that it secured around €1.3 million from the project’s profit under the form of interest. Taking out around €100,000 to be paid in bank interest, Dawson Place left another €1.6 million slice of gross profit to be shared between Avestus and Realta.

Castle Vernon

Realta made an initial €7 million advance to Ospak Connect DAC on January 18, 2017 and increased its investment to nearly €9 million during that year. The loans have an interest rate of 18 per cent. The vehicle also borrowed €2.5 million from Ulster Bank. Ospak immediately acquired the site off Clontarf’s Dollymount avenue with existing planning permission for 12 houses, and applied for 13 more on an adjoining piece of land.

Meanwhile, Avestus loaned just under €1 million to the partnership through its subsidiary Brookvest Summit DAC, which also borrowed nearly €280,000 from the bank. By the end of 2017, the site under development had a book value of €13.2 million.

Castle Vernon is now sold out, with 23 houses fetching an average €781,000 in the past three years. Assuming the last two achieved similar prices, total sales were in the region of €18.7 million.

This would leave a gross margin of around €6.5 million or 50 per cent over funds invested, similar to Dawson Place’s, with the terms of Realta’s intercompany debt funding apparently securing the majority of this – though accounts post the repayment of loans are not yet available.

Eglinton Rd

The proposed large apartment block on the corner of Donnybrook Rd, facing the bridge on the river Dodder, overcame local residents’ opposition to secure planning permission from An Bord Pleanála last August under a new strategic housing application. The Donnybrook Partnership formed by Avestus and Realta’s vehicles Acklam DAC and Martaban DAC had previously obtained planning permission from Dublin City Council for 94 apartments over seven storeys. This time, they went up to 12 floors and 148 homes.

Shortly after its incorporation in April 2017, Martaban set out to finance and assemble the site from several individual owners. It drew down the first €1 million tranche of an 18.75 per cent loan from Realta at the end of September, followed by a second tranche of €11.9 million one month later. Meanwhile, Avestus advanced €1.4 million in several instalments in 2017 through Acklam. The shareholders’ loans were partly refinanced before the end of that year with €8.6 million borrowed from Activate Investments. By the end of 2017, the two vehicles combined owed €627,000 to Avestus, €6.2 million to Realta and €8.6 million to Activate.

On June 21, 2017, the houses at Nos 1 and 3 Eglinton Rd changed hands for a combined €1.9 million. Then on November 3, Nos 5, 7 and 11 Eglinton Rd were bought for €3.5 million each. Of the development site, only No 9 does not appear on the Residential Property Price register. At the end of 2017, Acklam and Martaban’s balance sheets showed a combined €14.5 million book value for the property.

During 2018, Realta stumped up another €747,000 as planning work kicked in.

According to costings provided under the developers’ social housing obligations, apartment prices in the Eglinton Rd complex will range from €460,000 for the smaller one-bedroom apartments to €1 million for a two-bed duplex or a three-bedroom flat with the best views. The projected revenue from all 148 units is €87.7 million excluding Vat. This includes a €4 million forecast profit – not including development costs such as fees and finance interest, which would in part be paid to Realata and Avestus companies.

Bridgegate

Seamus and Philomena Lappin had plans to build 281 homes with their company named after the local townland, Rathgory Developments, in their home town of Ardee, Co Louth. However, those plans have been mired in difficulties including being dragged to the High Court by their lender, AIB, from 2014. The Lappins sold the 70-acre site under construction with just 42 houses under way to Earlstone DAC on July 20, 2018. At the end of that year, it appeared as a €6 million asset on the combined balance sheets of Earlstone and its partner company Altcar Connect DAC.

Three weeks earlier, Earlstone had started to borrow €4 million from Realta. Meanwhile, Avestus had placed just over €450,000 into Altcar. The two companies also secured funding from Bank of Ireland, reporting €21.3 million in “capital commitments contracted but not provided for in these financial statements” in their latest accounts to the end of 2018. They have not yet reported how much of those funds were drawn down, or if they would refinance any of Avestus and Realta’s initial funding.

The new developers focused on the section of the site already under development. In 2019, they obtained planning permission to increase the number of houses from 55 to 65 in that first phase. In their application, they also announced plans to build out the rest of the estate later, also with a slight increase in the number of houses to 159 in a second phase. It is not clear yet whether an apartment block planned initially will go ahead.

At the end of 2019, they started to sell completed houses. According to the Residential Property Price Register, 28 have changed hands so far for €208,000 on average. Asking prices for the remaining units range from €215,000 for two bedrooms to €275,000 for a four-bed. Assuming the remaining units sell for an average €225,000, this phase may end up generating over €14 million in total revenue.

Monterey

As its name does not suggest, the Monterey development is located far from the popular Californian seaside town – in south Dublin’s Sandymount neighbourhood – though it does contain a Monterey pine tree.

Realta started to loan funds to Marshona DAC on March 14, 2018, advancing €6.2 million to the company that year. At the same time, Avestus lent €688,619 to Arkdale DAC, its vehicle for the project. The partnership between the two companies has since raised an undisclosed amount of debt from UK-bases specialist property lender GreenOak. By the end of 2018, they reported ownership of a development site worth €7.7 million.

They obtained planning permission from Dublin City Council for nine luxury homes on a site assembled at the back of houses off Park Avenue, which was confirmed on appeal in 2019. Neither these land transactions, nor the reported sale of four of the new homes, have yet appeared on the Residential Property Price Register.

Agents Knight Frank, however, have told reporters that five remained, at prices ranging between €1.695 and €1.995 million. If confirmed, this would mean the nine units would gross a total of €16.6 million.

Brighton Road

One month ago, the Brighton Road Partnership formed of Abindon Connect DAC and landowner Marmont DAC lodged a planning application for 21 houses and a five-story block of 37 apartments on an infill site sandwiched between Leopardstown racecourse and the back of houses on Foxrock’s Brighton Road.

This is the Avestus/Realta partnership’s second attempt, having been refused permission on appeal last year after planning authorities highlighted insufficient capacity in the neighbouring sewerage network, the need to preserve trees in the leafy neighbourhood and objections from the Embassy of the Netherlands that balconies would overlook its residence. This time, the developers propose to build their own sewer through the racecourse, import 13-metre-high mature trees at a cost of €46,500 to maintain vegetation – and they have moved the tallest buildings away from the Dutch ambassador’s back garden and tennis court.

The project is an expansion of a scheme previously dreamed up by developer David Agar, who had applied to build six luxury detached houses there in 2015 after acquiring the site from separate owners for a reported €22 million at the height of the boom – only to be refused planning permission for insufficient density. Mortgage documents show that Marmont acquired the plot previously owned by Agar through his company Sammark Property Ltd, now in liquidation.

On May 29, 2018, Realta lent €4.2 million to Marmont. Weeks later, the properties forming part of the development site started to change hands. For its part, Avestus placed over €460,000 into Abindon. The two companies also borrowed a combined €5.5 million from GreenOak. By the end of the year, their balance sheets carried a property worth €10.4 million.

The latest planning application for the Brighton Rd development includes an offer to the local council to buy five apartments for €2 million to comply with social housing requirements. Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council acknowledged that the proposal, but noted that “the unit costs exceed the council’s approved acquisition costs thresholds”.

The costings provided by the developers show that they intend to generate €25 million in revenue from the sale of all units, including €1.4 million in profit and €9 million in development costs that would be partly paid to Avestus and Realta affiliated companies.

Mariners Way

In September 2019, Aguero DAC and Mowhan DAC jointly applied to An Bord Pleanála under the name of the Skerries Road Partnership for a strategic housing development of 117 houses and 48 apartments in Rush, Co Dublin. Among the 180 submissions received from the public, two of the many that followed a similar template came from senior local Fianna Fáil politicians: Senator Lorraine Clifford-Lee and TD Darragh O’Brien, who has since become minister for housing.

While he was keen to point out that his letter was “an observation and not an objection against homes being built on this site,” O’Brien proceed to detail reasons why the proposal should be rejected over seven pages. These included local road traffic capacity and safety, excessive housing density, flooding risks and environmental pressure.

Regardless, the planning authority gave its green light on January 17, 2020. In the background, the development’s vehicles were already at work. In December 2018, Mowhan borrowed €5.2 million from Realta and used €3.9 million of that to acquire the site. The contribution of Avestus through Aguero, or any other source of funding, have yet to be reported.

Roselawn

Aberdour and Roselawn were two houses on the Stillorgan Road dual carriageway in the Dublin suburb of Foxrock. Aberdour, in particular, had a checkered history. The late developer Philip Craughwell, who died in 2011, had secured borrowings from AIB against the property back in 2006 through a company called Tailworth Ltd. In 2013, Nama appointed receivers to the company over the debt.

Five years later, the site remained “occupied by an existing partially constructed detached house, formerly known as Aberdour” while its pedestrian right of way to the N11 road was “unsurfaced and overgrown”, according to planning inspectors.

At that point, the partnership between vehicles Abluvio DAC and Macium DAC kicked into action. In July 2018, Realta lent €4.6 million to Macium while Avestus advanced nearly €900,000 to Abluvio. They also borrowed €5.6 million from GreenOak. That same month, Macium acquired Roselawn for €2 million. The price paid for the much larger Aberdour site and its existing planning permission for 48 apartments wasn’t reported but, by the end of the year, the partnership booked development property assets worth €10 million.

Within the first half of 2019, they obtained permission from An Bord Pleanála for two blocks totalling 142 build-to-rent apartments. Costings provided as part of compliance with social housing requirements put the final value of the development at over €58 million. In line with new build-to-rent requirements, the planning authority imposed a condition that the complex must be owned by an institutional landlord for 15 years, and any plan to sell the apartments individually after that period will require separate planning permission.

Debt filings show further draw-downs from Realta and GreenOak in 2019 and 2020 as construction went under way, with financial details yet to be reported.

Kinsealy Lane

The vehicles established at the end of 2018 to build 48 houses on agricultural land within walking distance of Malahide Castle in north Co Dublin have yet to file accounts or register charges from their lenders. The only information available about the development, therefore, comes from its planning history.

The initial plan for 55 homes has been scaled down to 48 in the face of successive planning hurdles. Fingal County Council first refused permission in November 2019 because the local Irish Water pumping station was already at full capacity and wouldn’t be upgraded until the end of 2021.

After the developers appealed to An Bord Pleanála, the inspector assigned to the case came to the same conclusion last May and recommended a confirmed refusal. By September, however, the board found that Irish Water had a contract in place for the station upgrade and gave its green light on the condition that the developer secures a connection agreement with the utility before starting construction.

Blackhorse Avenue

The outcome of a planning appeal is due any day now after Dublin City Council refused permission for two blocks totalling 90 build-to-rent apartments on this former warehouse site, advertised in the fashionable neighbourhood of Stoneybatter (but really in Cabra).

Initial planning permission failed because the building, up to seven storeys high in parts, would seriously overshadow its neighbours. Its strong points, however, include agreements with bicycle- and car-sharing operators to locate stations in the complex.

The project is at an early stage, with no financial information reported yet by the vehicles incorporated in 2019 to carry it out.

Bay View

The site of the former Baldoyle racecourse is Avestus and Realta’s largest bet to date. Bought by Sean Mulryan amid the Celtic Tiger frenzy, it was repackaged as a residential development with plans for hundreds of homes stretching from the beach to the new Dart station at Clongriffin.

Then Mulryan’s business was taken over by Nama. Anglo’s loans to Helsingor Ltd, the vehicle established to develop the Baldoyle site, were transferred to the agency, which appointed receivers. Helsingor had €80 million in net liabilities in 2013 before Tom O’Brien and Simon Coyle of Mazars moved in. A vast undeveloped section of the old racecourse turned to wasteland.

In 2017, the receivers obtained planning permission for 379 apartments, 171 houses and a village centre with a shop, creche, and cafe. Then they put the 125-acre site back on the market, asking for €42 million. In their sales pitch, they suggested that the entire property, code-named Project Shoreline, could eventually carry 1,600 homes.

The winning bidder declared in October 2019 (though reportedly below the asking price) was an Avestus-Realta partnership. To fund the purchase, they secured debt funding from Activate Investments. None of the companies involved has yet filed accounts for that period, but rolling phases of completed houses have now started to sell with asking prices starting at €410,000 for a three-bedroom semi.

Belvoir

Kilmacud House is a 19th-century stately home adorned with a neoclassical cut-stone pillar portico in Stillorgan, south Dublin. Like many similar protected structures, its ownership drifted from the historic Anglo-Irish gentry to religious orders and, in the 1990s, the Victory Christian Fellowship.

The independent church, led by pastor Brendan Hade, acquired the building and surrounding grounds as an investment property. With the introduction of direct provision at the end of the last century, the Victory Christian Fellowship first used the building to accommodate asylum seekers under contract from the Government. Then in 2006, the organisation borrowed from Bank of Scotland against it and other properties to fund the construction of its megachurch in Firhouse. This didn’t work out, with cost overruns plaguing the project. The financial crash finally derailed the plan to sell Kilmacud and the church’s original building to regroup in Firhouse and pay down debt.

Seven years on, the bank appointed receivers to the Victory Christian Fellowship’s €18.6 million in debt and secured properties. The church fought repossession all the way to the Appeals Court, finally losing the case in 2015. The receivers put the properties on the market and, while Firhouse is now the Church of Scientology’s Dublin centre, Avestus and Realta’s vehicle Macium DAC snapped Kilmacud house in March 2017 for €2.8 million. A corresponding €3.6 million development asset appeared on its balance sheet and that of its partner company Abundius DAC at the end of that year.

Realta loaned the required €2.9 million to Macium a few weeks before the site purchase at an interest rate of 18.75 per cent, then topped it up the following year with another €800,000. Meanwhile, Avestus advanced nearly €420,000 to Abundius. Their partnership was initially refused planning permission to convert Kilmacud House into five apartments and build another 55 units in two four-storey blocks. Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council rejected their “significant overlooking, shadowing and overbearing impact” on neighbouring properties.

The developers, however, appealed with a revised proposal taking out five apartments and received the green light from An Bord Pleanála in January 2018. They borrowed €4 million from Activate investments to begin construction and, by the end of that year, had another €11.5 million in finance contracted to them.

Costings provided in planning documents under social housing obligations show that the developers valued the completed property, branded Belvoir after its historic name, at €27.6 million including Vat. Richmond Homes disclosed in October 2019 that an unnamed institutional investor had acquired the complex for €28 million. The purchaser was in fact Avestus’s own Irish Residential PRS Fund, which is now preparing the apartments for rent through its new in-house letting agent Havitat.

Ashfield Place

Ashfield College, a long-established grind school in south Dublin, was among the victims of the last recession. In 2009, as soon as the summer exams were over, it made its staff redundant and went into liquidation. Its business name has since been used by a separate company, City Education Group. The school’s buildings in Templeogue, however, were the property of college directors Graham Byrne and Dawn Maye, who were left to deal with creditors and receivers.

On April 21, 2017, Realta loaned €4.3 million to Motolph DAC at an interest rate of “up to 17 per cent”. One month later, the company purchased the Ashfield College site from Nama. Receivers to Byrne and Maye’s assets had obtained planning permission for 16 houses there in 2015. By the end of 2017, Motolph booked a €5.3 million balance sheet value for the site and any works started on it. In late 2017 and in 2018, Realta advanced over €1 million in further finance as construction progressed.

Meanwhile, Avestus invested €636,000 in the project through Arantoc DAC, and AIB loaned €3.2 million. Once bank finance was secured, the initial investors received repayments totalling €1.9 million on their advances, leaving a funding pot of €7.7 million after refinancing.

So far, 15 houses have been sold for a total of €9.2 million and one of the larger, four-bedroom units is for sale at an asking price of €749,500. If this is achieved, the full development will have sold for just under €10 million, leaving a margin of over €2.2 million to return on the funds provided by Avestus, Realta and AIB – that’s 30 per cent.

Sandyford Central

When developer John Fleming’s property empire collapsed in 2010, one of the sites left idle was that of a former Aldi warehouse in an industrial estate being redeveloped as a residential area in Sandyford, across the street from the Stillorgan Luas station. Anglo and ACC Bank first appointed receivers to Fleming’s vehicle for the property, Tivway Ltd. Then Nama took over the banks’ security over the site and installed its own receiver, Pearse Farrell of RSM (since absorbed by Duff and Phelps).

Farrell obtained planning permission for 459 apartments on the property in 2018 and promptly put it up for sale, highlighting the potential to build more thanks to relaxed planning requirements under new build-to-rent specifications. Documents filed by the receiver show that he sold the site in February 2019 to Sandyford GP Ltd, a joint vehicle of Avestus and US investment fund Ares Management, for €44.5 million.

Sandyford GP and its investors operate as a limited partnership, a corporate form that files no public financial information. However, accounts filed by Ares intermediary holding companies in Ireland and in Luxembourg show that the fund invested €7.6 million worth of equity in the project and loaned another €38.6 million at an interest rate of 15.5 per cent, covering the entire site value. Later in the year, after borrowing from GreenOak, the partnership reimbursed €23.6 million of the funds advanced by Ares from Luxembourg.

As suggested in the site’s sale pitch, Avestus went back to An Bord Pleanála with an application for a larger development under build-to-rent rules – this time for 564 apartments, a creche and a cafe in six blocks of up to 17 storeys. This was granted last year.

Costings provided under social housing compliance requirements show that the developer forecasts a €228 million final value from the complex.

Streamstown

The Currency previously reported on the joint venture between Avestus and Cerberus to take over the next phase of the Streamstown Wood development in Malahide, Co Dublin from developers Donal Caulfield and Leo Meenagh. After putting a first phase of 44 houses on the market at the time the financial crisis hit, Caulfield and Meenagh’s company Glenlake Properties went into receivership at the request of Ulster Bank.

Cairn Homes bought the undeveloped part of the site, increased the number of permitted houses from 22 to 32 and put the property back on the market. Streamview Connect Trading DAC, which bought it on July 11, 2019, is a joint vehicle of Avestus and US investment fund Cerberus through their common holding company Promontoria ACP.

Filings by Promontoria ACP show that Cerberus has so far made a €2.2 million equity investment in the joint venture, nearly all in the weeks preceding the site’s purchase. Avestus, for its part, has put in €57,618.

The two partners have also provided intercompany loans to the project, with Cerberus advancing €3.1 million and Avestus just under €80,000 in 2019, bringing their total investment in the joint venture across equity and debt to €5.5 million at the end of that year. At the time of the Streamstown purchase, they raised additional debt finance from GreenOak and have yet to report the amount borrowed from the lender.