The phone rings. It is a Monday evening in February 2002, and the clock has just edged past nine o’clock. Gary Kennedy is at his kitchen table quietly working; a dog lies by his feet. Just 44, he is group director of finance and enterprise technology at AIB, a financial powerhouse with operations in Ireland, Britain, Poland and the United States. Kennedy had joined the bank five years before, leaving a stellar multinational career behind him where he had run a core division of Nortel Networks Europe across 45 countries. Then the phone rings again. Everything changes.

*****

On the other end of the line that evening was Michael Buckley, the Cork-born chief executive of AIB, who previously was managing director of NCB stockbrokers.

A massive fraud had been discovered in AIB’s United States subsidiary, Allfirst.

“It was one of those sort of wake up moments,” Kennedy recalls 17 years later. “It wasn’t a phone call I was expecting on a Monday night. We all had to go into overdrive from then on. I didn’t go to bed that night. I was up working through a plan on what needed to happen next.”

Early the next morning, Kennedy and a small number of AIB’s senior team met in secret inside the bank centre in Ballsbridge, Dublin 4.

AIB was a listed business, enmeshed not just in Irish business but in Irish life.

The bank was not unfamiliar with trouble, having survived a Dirt tax avoidance investigation a few years earlier. But it was facing what was then its greatest crisis.

Buckley had just discovered that an American trader called John Rusnak had gone rogue. The bank at that point did not know just how big a financial hole it was facing, but he knew it was going to be very big.

AIB had to scramble to find out what happened. It dispatched a team to America while its senior management team back home, Kennedy included, prepared for the worst.

“We had to bottom out the extent of the problem quickly because we had an obligation to announce it to the market,” Kennedy says.

By 7am on Wednesday morning the bank felt confident enough to announce that its Baltimore division had generated a staggering loss of up to $750 million in bad bets placed by Rusnak on various currencies.

“We got ourselves 56 hours. We had to put people on a plane over there to work through it. It was pretty character-forming for a lot of people. We had to do a lot of work over there and we had to reposition our investment quickly.”

The fraud, Kennedy now says, had a “catastrophic” impact on the bank. Its stock price fell by as much as 23 per cent and there was a big run on deposits. It was a torrid time.

“There was a body of work to get us to being able to make that market announcement,” Kennedy tells me. “Then it was working our way through regulators on all sides of the Atlantic explaining what had happened. But we got there.”

Almost two decades later, I ask Kennedy what he learned from the experience? “Probably the biggest lesson was around how companies sometimes can let complacency creep in,” he says.

“We were supposed to only have small amounts of trading focused on customer positions over there. We weren’t supposed to be trading on our own book. All of the trading on our own book was supposed to be done back in capital markets which was in the IFSC in Dublin at the time. But that was allowed to happen. People fell asleep at the wheel in terms of responsibility and ownership.”

“It is typically people who are making progress who engage and the people who are lagging behind who don’t turn up.”

Gary Kennedy is calm today recollecting the Rusnak fraud, which was a seismic moment in Irish banking. Yet the $691 million losses incurred look almost small versus those that occurred six years later when both the Irish banks and economy collapsed.

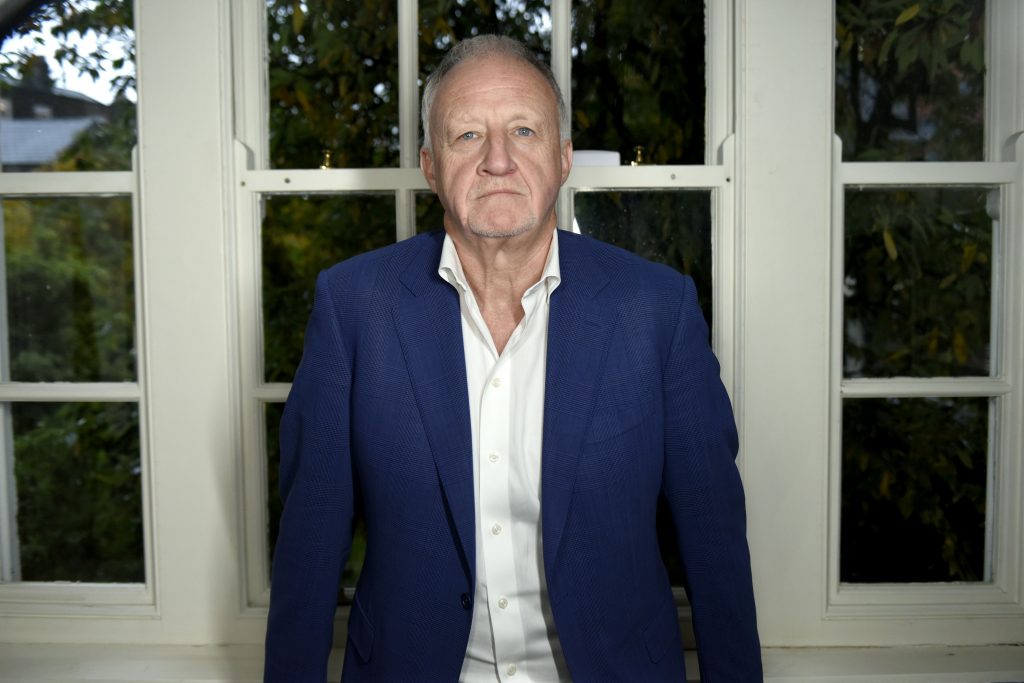

Kennedy is meeting The Currency in his role as co-chair of Balance for Better Business (B4BB) a government-backed initiative trying to create greater gender balance at a senior level in Irish companies.

But it is impossible not to ask him, too, about his remarkable career at the boardroom table. Kennedy tackles every question, bar one in relation to Green Reit, head-on. He is intelligent, straight-talking and honest.

It is these characteristics which have taken him to the top of the corporate world.

Kennedy is chairman of Greencore, a £1.1 billion listed food company, and Connect Group, a listed British distributor of newspapers, magazines and consumables.

He was until recently chairman of Green Reit, which sold this autumn for €1.34 billion. He also previously sat on the board of the IBRC and Elan. Combined, they give him experience of every aspect of being a director, from the highs to the lows, across multiple sectors and multiple cities.

In July 2018, Kennedy was asked by the Minister of State for Equality David Stanton to become co-chair of Balance for Better Business which is campaigning to promote more women to company boards and senior executive positions.

Its first target is to ensure that 33 per cent of all directors on the ISEQ 20, the top twenty listed Irish firms, are female by 2023 and 25 per cent for other listed companies. It also set itself the goal of no “all-male” boards by the end of 2019.

Kennedy said he decided to co-chair Balance for Better Business because he knew that Ireland was lagging behind its international peers and this was having a detrimental impact on the quality of Irish boards. His co-chair is Brid Horan, a former deputy chief executive of ESB, who also chairs Nephin Energy and has a range of other board interests.

“I go back a long time with Brid. We spent about 10 years together on the board of the IDA from 1995 on working originally with Kieran McGowan and later Sean Dorgan. It was a very interesting period in the development of the Irish economy and the role of FDI in creating the real Celtic Tiger,” Kennedy said.

“We also had another connection through the 30% Club in Ireland [which promotes females in all levels of business]. Brid was very heavily involved in that and we thought Balance for Better Business was a good opportunity to promote more gender diversity in boardrooms.”

Kennedy says bluntly when he joined B4BB in July 2018: “The stats weren’t good.”

“If you take the ISEQ 20, just over 14 per cent of those companies had female representation in terms of their boards,” he said. This statistic he said was even worse once you stripped out a handful of firms with 25 per cent female directors, which disproportionately drags the average up overall.

“Progress has been made but it was only small incremental progress. The top 20 was 18 per cent (female directors) and we have moved to just short of 21 percent. It is not exactly hall of fame,” he explained. “We have a long way to travel.”

“Percentages hide an awful lot of things. There is quite a big disparity between the top 20 listed companies and the rest,” Kennedy added.

“One thing that is quite alarming is that when we started this initiative back in 2018 the number of boards that had zero female representation was actually 38 per cent,” he explained. “Of the ISEQ 20, 10 per cent had no female representation. But with other (listed firms) it was 57 per cent. That was a particularly alarming statistic.”

“By the time we came to do our report in 2019 all the ISEQ 20 had at least one female representative but there was very little progress in the other listed companies,” he said.

“They had only moved from 57 per cent to 48.5 per cent. This is an area we have zoned in on and are passionate about changing.”

Kennedy said the response from firms to gender diversity was mixed. “It is typically people who are making progress who engage and the people who are lagging behind who don’t turn up,” he said.

“Women are by far the most underutilised economic asset in the world. It is a no brainer.”

B4BB will miss its target of having no “all-male” boards for listed companies by the end of this year, he said. “It is most disappointing. We have another report coming out this year. We have not made an awful lot of progress. I have had proactive engagement from some to tell me why it is not right for them. But I have had very little interaction from a lot of others.”

“My philosophy is that you can make any excuse you want if you don’t want to make progress,” Kennedy said.

He said some companies complained that it took time to rotate male directors off boards; others said their all-male boards were locked in for various reasons; while some said they were too busy trying to survive to worry about it.

“When you run a business, you need to look at things in a cohesive fashion. I don’t really buy the excuses to be honest with you,” Kennedy said. “You will get companies who will tell you say their articles of association only allow five directors. So, change your articles of association. It is no big deal. You’d do it for other things.

“Some companies say they are waiting for men to retire. Why not create another slot in the short term? You will get the benefit. The business case for diversity and gender balance is very well proven in terms of better quality of discussion and decision-making.”

“There is no legislation in Ireland from a governance perspective to force diversity. We would much rather people were responsive and listened to the message. It takes leadership and freshness of thinking,” Kennedy said.

He said proxy advisory groups as well as some institutional investors were pushing for more women on board.

“You would like people to feel it is the right thing to do rather than react to a push,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy said that with Ireland close to full employment, businesses which did not promote more women to senior positions risked falling behind.

“Women are by far the most underutilised economic asset in the world. It is a no brainer. It does mean you have to change your philosophy and outlook.

“You get every excuse in the book thrown at you [for not promoting women]. They don’t have enough experience and so on. Someone had to take a decision with me the first time I became a non-executive. I wasn’t born a non-executive! Someone has to take that first decision.

“If you have a fully mature board then you will have a blend of experience, so it is always easier to bring on somebody with less experience. A lot of this is about changing mindset.”

“There is unconscious bias [against women] but unfortunately in Ireland there is also conscious bias. That needs to change. It is simple things. When you go to refresh your board and you are looking for whatever skillsets make sure that 50 per cent of the candidates that are produced are female.

“It is not good enough to look at only people already on boards and just recycle them. There is zero shortage of well qualified very experienced female business leaders in this country.”

Kennedy said that while B4BB was initially focused on listed company boards, it planned to go wider in time.

“You have to get to the C suite and look at who is coming through in terms of succession and you can’t ignore private companies either. We have made a lot of progress with B4BB towards our overall targets, so that is certainly very positive, but we have to keep progressing.”

Tom Lyons (TL): Do you think too much testosterone has led to worse decision making in Irish business?

Gary Kennedy (GK): Unqualified, I can say that where you have a better balance on a board in terms of gender you have a better outcome. There is more emotional intelligence and decisions are coming from a more informed position. Fifty per cent of the world is female. Seventy per cent of spending is driven by females. By not having any females you are losing out on a lot of insights into purchasing and buying habits. The quality of discussion and decision making is better. I have certainly seen a benefit in terms of strategy (on boards I have served on).

TL: How do you avoid companies stopping at just one female director?

GK: It can’t be tokenism. One female on a board can be quite isolated. It is only a start. Two is not great because people may think well they are not isolated so they are done. Ideally if a board is say 8 or 9 people you need three females or three men. A 40 per cent gender split is ideal. It is never going to be exactly fifty-fifty. It is also important to ensure women are not just non-executives but also chairs and taking on senior non-exec roles like being senior independent director or chairing significant committees.

*****

Gary Kennedy believes that change will only come from above and below. “There is always a pull and a push,” he reflects. “You need to have a leadership at the top who are prepared to change. You also need a strong push from the female gender within companies.” Kennedy said the generation from their 20s to mid-30s both wanted and expected more diversity. He said companies who wanted to hire the best talent needed to promote more women. “That is a good push but you still need a chair and a CEO to pull.”

TL: What have you done as a chairman to promote women on boards?

GK: If you take Greencore as an example, we currently have six non-executives on the board. We also have three executive directors and a company secretary. Of six non execs, which includes myself, we would have three females. Our three executive directors are all male and our secretary is female. We have made substantial progress in terms of our non-exec community.

TL: What was the board of Greencore like when you joined?

GK: I joined the Greencore board in the tail end of 2009 so ten years ago. There were no female members of the board at that stage. There was a female company secretary. Nobody on the board. I had an opportunity when I was asked to become chairman in January 2013. I had to bring on four other non-exec directors because of a sequence of people retiring. We took that as an opportunity to do different things. We brought in a geographic mix of people between the UK and Ireland. We looked at skill sets for people with a food industry background and others with other areas of expertise. I firmly believe in a blend at board level. I also had an opportunity luckily at that time. There were some very high-quality females who came on board.

The board of Greencore includes Sly Bailey, its senior independent director, who previously led Trinity Mirror plc. Heather Anne McSharry, a non-executive director, was previously managing director of Reckitt Benckiser and Boots Healthcare. Helen Rose, a former chief operating officer of TSB Bank, a subsidiary of Banco de Sabadell, is also a non-executive director. Greencore’s company secretary is Jolene Gaquin, who previously served as head of legal and compliance. By any measure, these directors are an impressive contingent. In its IPO prospectus, however, Green Reit, which Kennedy also chaired, had four directors. All four directors were male when the property company floated in 2013.

TL: But what about Green Reit?

GK: We IPO’d that business in July 2013. The directors came on board at that stage. A couple of years into it (December 2017) we were changing a director and Rosheen McGuckian [the chief executive of NTR] joined the board. She is fantastic. It is a pretty good board. Forget about myself, but with Gary McGann [a former CEO of Smurfit Kappa] and Jerome Kennedy [a former KPMG partner] there were no shrinking violets. When Rosheen came on board it stepped the game up again in terms of quality of input, challenge and decision-making. Having said that, only 25 per cent of the non-execs were female. I would give myself a little tick for that, not a big one.

TL: And Connect plc (a distributor of newspapers, magazines, books and consumables) which you also chair?

GK: Connect is a smaller cap company in the UK. In terms of non-execs there, we have 25 per cent currently. It is harder on smaller boards (to get gender balance) as you may only have three or four directors. But you can use any excuse in the book. You just have to get on and do it.

“The kiss of death in a multinational”

Gary Kennedy was educated by the Christian Brothers in Armagh. His father worked in the credit union movement and his mother worked in the civil service. Northern Ireland was riven with violence and unrest as he was growing up and he had no desire to stay there.

“I was 17 in 1975 which was not a good period in Irish history in terms of the troubles,” Kennedy recalled.

He went to Lancaster University to study accountancy and finance. “It was a very unpleasant time. I had a great childhood, but it was always there. [The Troubles] kicked off in 1969 when I was 11. The early seventies were not good. I wanted to get out of Northern Ireland.”

After university Kennedy joined accountancy firm Deloitte, which dispatched him to its Limerick office. For the next seven years, he worked as an audit manager for multinational clients along the western seaboard. One of these clients was a Canadian telecoms company called Nortel Networks. The Ontario headquartered company traced its roots back to 1895 and the Bell Company of Canada. It was one of two companies which received the patent rights for the telephone from Alexander Graham Bell.

Nortel, when Kennedy joined it in 1985, was considered one of the most exciting companies in the world.

The Financial Times described it as a “pioneer in modern telecoms technology”, making products like switches, routers and fibre optic cables for the world’s telecoms companies.

Kennedy swiftly rose through the ranks of a company on the march. He started in finance, and, when the call came, he moved to Canada. Nortel then sent him to the UK to work in its European operations and he moved into general management.

Still in his 30s, he ran its enterprise networks business with responsibility for 45 countries in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

“It was probably the best job I ever had in my life,” Kennedy reflects.

His job required constant travelling, gaining him experience in five different geographies. It was rewarding work but for personal reasons, Kennedy wanted to travel less.

“I was under significant pressure to move overseas again. In six months, I turned down Australia, China, California, Western Alberta and Dallas.”

“That is the kiss of death in a multinational when they know you are not going to move. I loved the company. I loved the job. I loved the experience. But my kids were at an age where we needed a bit of stability education-wise and a home that they could call home.”

Kennedy started to look around and towards the end of 1996 he was convinced to join AIB. It was both a banker to Nortel and a user of Nortel’s services so it was not entirely unfamiliar territory.

Tom Mulcahy was the chief executive of AIB at the time and he personally convinced Kennedy to join the bank.

For a time, it looked like Kennedy had missed out massively by joining AIB.

Sure, the bank was doing well but in the years after he left it, Nortel exploded in size.

Nortel was, at its peak, ten times larger than the second biggest company in Canada with a market cap of many billions in the run-up to the dotcom bubble. When it burst, it sent Nortel into a long spiral of decline and eventual bankruptcy in 2009.

Joining AIB was the first of several major turning points in Kennedy’s boardroom career. Like so much in business, luck, as well as talent, can determine things.

“It was a bus I missed”

At only 39, Gary Kennedy was made AIB group finance director in 1997. This gave him a position on its board, which back then was chaired by Lochlann Quinn, the cofounder of Glen Dimplex. “I had a very far-reaching role,” Kennedy recalled. It was more than just a finance role with responsibility too in strategic planning.

The year before Kennedy joined AIB, it had bought a stake in a bank in Poland called WBK. Kennedy helped lead the acquisition of an 80 per cent stake in another Polish bank called Bank Zachodni in 1999.

The following year, he was involved in merging the two Polish banks to create a business with total assets of €5.4 billion and over 10,000 staff.

“It was a big change that was driven by the personal dimension. I was based in Bankcentre (in Dublin 4) but there was some travel,” Kennedy tells me.

“AIB was in Poland in a small way but I helped buy the second bank there. That was a fantastic experience. I was on the board of the US operations as well. There was a lot of machinations there with Rusnak…”

Kennedy and the entire AIB team knuckled down and the bank managed to survive the Rusnak affair. Soon it was growing again as the Irish economy took off and its foreign investments paid off.

In 2005, Michael Buckley prepared to step down. Kennedy, by then 47, was seen as one of a small number of contenders vying to replace him.

He lost out however to Eugene Sheehy who had joined the bank as a teenager before rising through the ranks.

The Irish Times described Sheehy as a “safe pair of hands to run the Republic’s biggest and most profitable bank”.

Kennedy left AIB at the end of 2005, not long after Sheehy’s appointment. He received a payout as he left, so he was not under pressure to find work immediately.

In May 2005, he had been appointed to the board of pharmaceutical company Elan, so there were things to do.

Within three years of his departure, AIB, like Ireland’s other banks, was on the brink of collapse due to excessive property lending.

It required a state bank guarantee to keep it afloat, then a multi-billion euro bailout, and 99 per cent of its shares went into state control. Sheehy was forced to step down in May 2009. Sheehy returned to college to study and practically disappeared from Irish corporate life.

TL: Missing out on the top job in AIB must have been tough. But looking back, was this a sliding doors moment in your career?

GK: It was, to be brutally honest with you. On a personal level, it was a disappointment at the time. Looking back with hindsight, it was a bus I missed for lucky reasons to be honest with you. I probably wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you today. You would be persona non grata having gone through that. To some extent, I got a little bit of luck even though I didn’t realise it at the time. It was important for me to go do something else. There was no point getting frustrated. I am glad I did what I did.

Life after AIB: from Elan to Anglo

When Gary Kennedy left AIB he was not yet 50. “I was still relatively young, but I had been working for about 30 years. I decided to do something different.”

He was on the board of Elan as a non-executive director, and gradually this took up more of his time. Elan had almost gone bankrupt a few years before Kennedy joined, but by 2005 it was back on track boosted by sales of Tysabri, a drug used to treat multiple sclerosis, as well as an exciting pipeline of potential Alzheimer’s treatments.

Its experimental Alzheimer’s drugs failed, however, sending Elan’s share price nosediving. Being a board member of Elan was a rollercoaster, but it gave Kennedy invaluable experience of both the highs and lows of being a director.

Elan survived its woes and the business was ultimately sold for €6.3 billion to US-based Perrigo in November 2013. Kennedy proved himself as a non-executive director of Elan, and he was now in demand.

“I have been lucky working in great companies and enjoying what I did, notwithstanding some of the challenges,” Kennedy said.

“When you are working through crises you are working on adrenalin. There is a buzz out of that, but it is not something you want to do every day of the week.”

“But on the more positive side, building businesses and buying businesses, I very much enjoyed that. I very much enjoy what I am doing now seeing companies succeed and CEOs succeed.”

Elan was not the only corporate rollercoaster that Gary Kennedy was prepared to ride. In May 2010, he answered the government’s call by taking up a non-executive directorship role on Anglo Irish Bank which had been nationalised the previous year. Anglo was the ultimate black diamond slope for any director, but Kennedy was prepared to step up to it.

He became one of three new directors of the failed bank (the others were Noel Cawley the chairman of Teagasc and solicitor Aidan Eames). The three joined existing board members; chairman-designate Alan Dukes, a former minister for finance; outgoing chairman Donal O’Connor; chief executive Mike Aynsley; and former Bank of Ireland chief executive Maurice Keane.

It was a demanding role with the financial future of Ireland, linked closely to the ability of Anglo’s board to tackle the horrendous issues facing it.

Under Dukes, Anglo’s new board aggressively reduced its balance sheet, raising billions for the state by selling off loan books, and tried to nurse good Irish businesses through the crisis.

It also dealt with tricky situations, like the fallout from the collapse of Sean Quinn’s empire, and managed relationships with various stakeholders including the Department of Finance. One of its smaller deals, the sale of Siteserv to the tycoon Denis O’Brien, later became very controversial leading to the state setting up a commission into Anglo, renamed IBRC, in the years after it was nationalised.

TL: What was it like to be a board member of IBRC?

GK: I found it good. It was intellectually challenging and full of rigour. There was a lot of issues to deal with but there was a good bunch of people around the table too. They were people who were focused on trying to get things done. It was extremely demanding in terms of time and the number of meetings and committee meetings. Being brutally honest about it, I am quite disappointed in how the government disengaged from the process in terms of enacting emergency legislation to liquidate the bank and not telling us about it. Effectively dumping us.

TL: Since the liquidation the state has set up an expensive and wide-ranging investigation into the new board and executive of IBRC that has gone on for years behind closed doors, despite there being no known evidence of any wrongdoing by its executive or board. Do you feel hard done by?

GK: We weren’t the guys that caused the problems. We were in there trying to fix them. You get dumped on a little bit. It is not a nice way to deal with people. I wouldn’t deal with people that way. At the time we had an indemnity (as directors against being sued). They tried to withdraw our indemnity. That is not a way to deal with people that have been doing something to try and help the national cause.

TL: You were on the board of Anglo for three years but have been, along with every director and senior executive, under investigation by the IBRC Commission for four years. Do you find it incredible that the state has let its investigation go on so long?

GK: Yes. But you know what? You sign on for these things. You have to be mature about it. But you know I would be disingenuous and telling you lies if I said I did think we were treated fairly. Do I let it worry me? Not particularly because I know we did the right thing. I am not going to waste my life worrying about it.

For legal and banking confidentiality reasons Kennedy can’t comment on the specifics of the IBRC Commission investigation nor can he comment on individual clients, so we don’t go there. Instead, I ask him about advice he would give others considering going onto a board, given his range of experiences, both good and bad.

TL: What would you say to anyone considering becoming a non-executive director?

GK: There seems to be a mystique about what happens in a boardroom. You can have great times, but you are stretched at times too. You have to think is it really what you want to do? Do you have time to do it? It is a full-on commitment when you join a board these days both from a shareholder and regulatory effect. Make sure you have the time and the mindset in terms of commitment. The second thing is you have to figure out is: is it the right company in terms of being the right business with the right type of business model?

TL: What do you look for personally?

GK: What excites me is companies that have loads of ambition and loads of desire. It has to be a space where you have an interest too. If you are going to spend time with it you might as well enjoy it. A board is only a mechanism between shareholders, management and money. It is a big responsibility. You have a multiplicity of stakeholders and you are never going to satisfy all of them. You have to figure out if I do this will this deliver value for a composite shareholder base and how do I engage with the company to help it? That involves trust and robust debates in terms of strategic planning. It requires you to get stuck in and support management in the execution of that strategy once it is agreed. It is quite an involved role being a non-executive director and not overly rewarded. But that is not necessarily why people want to do it. It is the intellectual challenge and rigour and also the chance to impart a lot of your expertise and experience while respecting different perspectives.

Stepping up to chairman

The first company Gary Kennedy chaired was Greencore. He has now chaired three PLCs, as well as being a co-chair of Better Balance for Business. Good chairs are critical to company success. It is to this topic we turn next.

TL: What does it take to be a good chairman?

GK: You need to be very committed to the role. There is a big difference in the amount of time you need to spend as a chair versus as a non-executive director. The chair is the person who spends most time outside of the board environment with the management, customer base and shareholder base. You need to develop a very good working relationship with the CEO and the team that is built on trust and honesty.

TL: What are you like as a chairman?

GK: I can tell you in the case of Greencore and the other companies I have chaired, there is no managed agenda. It is a very open culture. There is nothing hidden. You are all in it together and that only comes from trust going both ways. You cannot allow that trust to overspill into compromising the decision-making process. Of course, you want to be friendly but there are times when you will have different views or may want to do something differently. No surprises is a big thing.

One of the most important things for me is to be there as a sounding board for the CEO. I have done my thing in terms of my executive career. Where I get my kicks is in seeing companies succeed, and their CEOs and management teams. To do that you have to understand the business. In Greencore, I spend a lot of time in each of their business divisions and with the people who run those divisions in different territories. I don’t sit in a boardroom only. I will go and have dinner with them and try to understand what their issues are. I will go and see people down the line, meet their management structure and teams, just build up better knowledge and rapport. It means you come back to the boardroom much better informed.

TL: What is your leadership style as a chairman?

GK: Everybody has a different style of managing a board. Mine is open and inclusive. I never want a board member to come to a board and go away feeling frustrated because something didn’t get addressed correctly. You need to find a balance to allow dialogue, discussion and alternative views. But you also have to be able to draw things to a conclusion. Sometimes you have to be a bit more directive than looking always for consensus. Communication, like most things in life, is the most important thing.

*****

Gary Kennedy became chairman of Connect PLC in May 2015. Throughout his career, he has always had an interest in international markets, so this was a motivating factor in taking up the role. Unlike his other board positions, there is no obvious Irish connection.

“I was asked to throw my hat in for the job,” Kennedy recalled. “I had never really heard of the company before but I got to meet their then chair and their CEO and had a look at some of their plans and the challenges they had. It just seemed to be a good fit. I asked myself could I really interact with the management team? Would I bring something to it and do they have ambition? They ticked the boxes for me.”

Gary Kennedy was chairman of Green Reit from July 2013 until its sale for €1.34 billion to British property company Henderson Park Capital. Green acquired and developed a series of grade A office buildings including One Molesworth Street and George’s Quay Plaza in central Dublin and Central Park in Leopardstown. It also owns a logistics park in North Dublin, an office block in Cork and the Arena Centre in Tallaght.

Co-founded by Stephen Vernon and Pat Gunne, the business created huge value for shareholders, before its share price stagnated at a discount to the underlying net value of its properties, prompting Green to put the business up for sale.

“Green had probably the best team around in that business, but I am probably biased,” Kennedy laughs. “It was a very different model. It was a company with no employees. We had an external investment manager and a PLC board. Trying to figure out how to make sure we had the right governance from a shareholder perspective while still having that working relationship to do the right thing was a challenge,” Kennedy said. “In the end, it was a fantastic result for shareholders.”

“It is still very hard to sell. Most of us go to work to grow businesses, not sell them. But sometimes if you really believe in shareholder value you have to take the right action.”

TL: What was it like to sell Green Reit?

GK: Emotionally very hard. I had the same emotional reaction when we decided to sell the US business in Greencore. You are doing the right thing from a shareholder value perspective but there is something wrong if you are not emotionally attached to it. I have been doing business in the US for 30 years. It was the right thing to do to monetise from a shareholders perspective. We (Greencore) had an unsolicited bid which valued the business at a multiple higher than our overall business. In the case of Green Reit we had a structural discount in terms of our share price relative to our net asset value. We looked at a variety of ways of trying to resolve that. We picked a sale and we were right because not only did we close that structural gap… we got a bit of a premium. It is still very hard to sell. Most of us go to work to grow businesses, not sell them. But sometimes if you really believe in shareholder value you have to take the right action. It is their money, not my money!

TL: Did the government target the Green sale in its last budget by closing down a tax loophole that the purchaser of the business planned to avail of?

GK: I have no comment. It is done. It was in the High Court and the scheme of arrangement was passed. It is all done and dusted. The money is in escrow waiting to be distributed to shareholders.

TL: Will you ever team up with the Green team again to do something new?

GK: Stephen (Vernon, founder of Green) is probably moving into a different phase in his career. They (Vernon and Pat Gunne, Green chief executive) were an incredible combination. Stephen had a huge amount of experience combined with the dynamism and energy levels of Pat. But if you go behind them to the team, who are still there working with the new owners, whether it is Caroline McCarthy (Green chief investment officer) or Ronan Webster (Green director) or Niall O’Buachalla (Green chief operations officer), they are top-class people.

TL: How did you celebrate a billion euro sale?

GK: We go for a couple of pints. (Laughs.) The good thing about Ireland and Dublin is it is only a village. You meet people around. There are lasting friendships that come out of it. It is a bit like going to a funeral but there is no coffin. It was a happy ending. We haven’t gone for a pint yet mind you. No time!

TL: What is next in terms of the boardroom?

GK: I enjoy working. I like variety in terms of businesses. I like the flexibility of what I do now. I can be extremely busy or I can take some time off. I like the intellectual challenge. My time is coming towards the end with Greencore because of the number of years. If you take the new corporate governance guidelines, I should already be gone, but we are in a transition phase. We are in the middle of doing a refresh of the board and it has asked me to stay through that…

Green Reit is gone. Time doesn’t stand still. Hopefully someone still sees a bit of value in me! We have another Balance for Better Business report coming out. You can’t always solve a problem by just looking at the top, mind you. If you really want to take this to end game you have to start with when kids are born. Affordable childcare, flexible working arrangements and so on are all issues that need to be dealt with at government level. We are making progress, but there is a job of work still to be done.