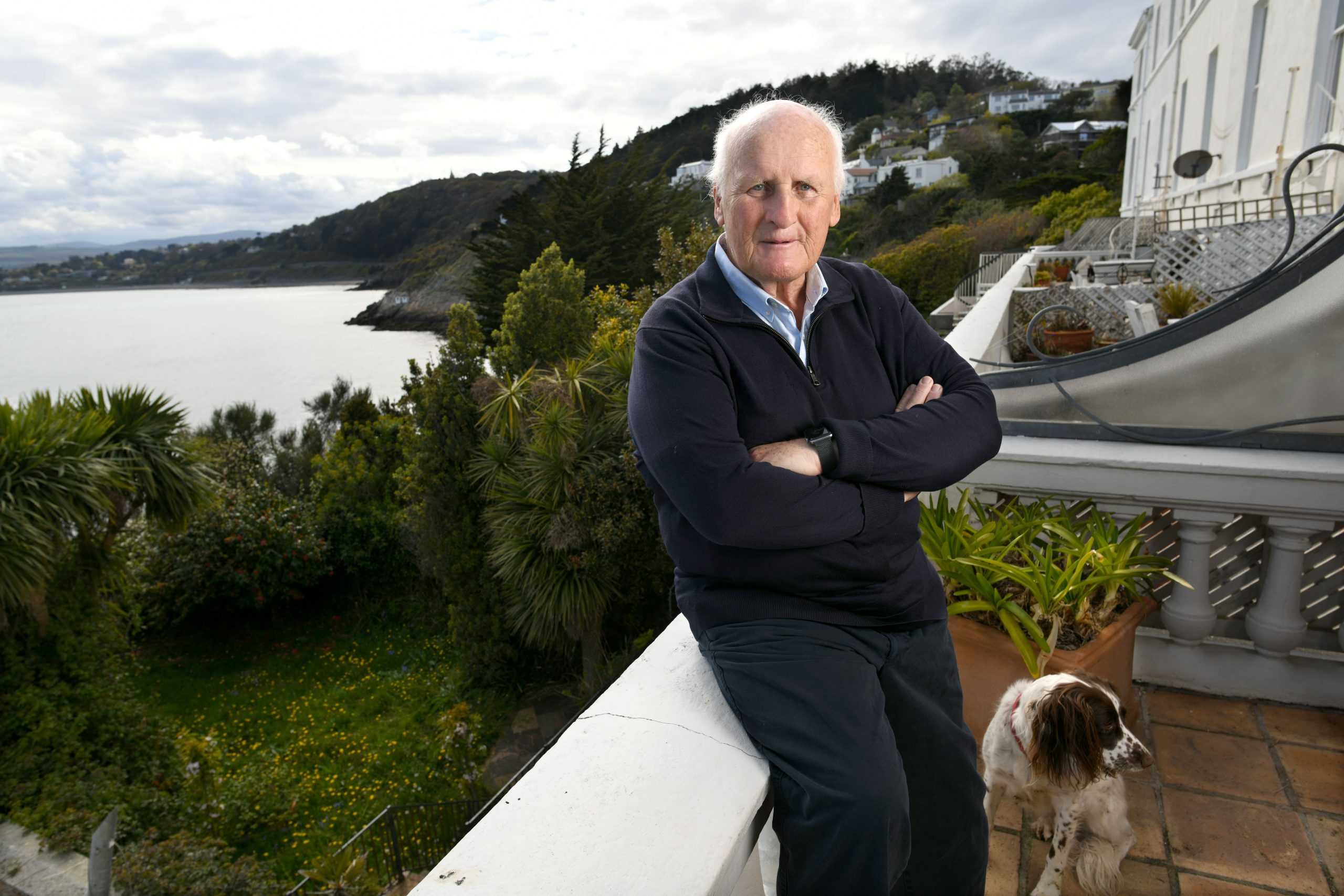

Colm Barrington is a firm believer in the concept of an iron fist in a velvet glove. A keen and successful sailor, the word glove has appeared in the name of most of his boats over the years. His main boat at the moment is called The Velvet Glove. “Be firm and strong, but outwardly gentle,” he says. Now 75, Barrington remains fit and exceptionally busy. When we speak, he has just returned from a session at the gym, and he talks about his upcoming sailing schedule. And, although he admits he should probably be retired by now, he remains…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to continue reading?

Introductory offer: Sign up today and pay €200 for an annual membership, a saving of €50.