On May 11, 2017, Michel Barnier addressed a rare joint sitting of the Oireachtas, less than two weeks after receiving a mandate from EU leaders to launch Brexit talks with the UK. With a few words of French, Ceann Comhairle Seán Ó Fearghaíl greeted the European Commission’s chief negotiator who held the branch of his glasses to his mouth, looking every bit the consummate European politician. Ó Fearghaíl then invited him to enter the chamber and deliver his speech.

In return, Barnier praised Ó Fearghaíl for his French and performed the expected Seamus Heaney quote – from Beacons at Bealtaine, Heaney’s poem to welcome new EU member states in 2004. Beyond the pleasantries, his core message was to pledge a united EU front to protect the Good Friday Agreement in upcoming negotiations. Barnier does not dwell on the content of this speech in his new book, La grande illusion, his four-year “secret Brexit diary” to be published in English in October (the translations below are mine). Instead, his entry for May 11, 2017 provides context.

While his address to the Oireachtas acknowledged his audience as “the representatives of the people of Ireland, in all your political diversity” (ignoring the absence of unionist members at the time), he remarks more specifically in his book: “The Government and the prime minister at its head, called Taoiseach in Ireland, my friend Enda Kenny, is on the right. Behind him are the members of his party Fine Gael, and facing them are the opposition, including Fianna Fáil and Labour. My lectern is in the middle. Two metres behind me sits Gerry Adams, president of Sinn Féin, who became an Irish deputy in 2011.”

The description of Adams’s position looming behind him is anything but innocent. In his book, Barnier spells out what he heard from John Hume and David Trimble in 2000, when he was in charge of the PEACE funding programme for reconciliation in Northern Ireland as EU commissioner – conversations that he only alluded to in his address to the Oireachtas. “Both said the same thing to me, with the same words: ‘What brought us to the table was not London, Belfast or Dublin, it was Brussels and the PEACE programme.’”

When it comes to Ireland, Barnier literally regards himself as a peacekeeper.

On the next page, Barnier further explains what has shaped his personal view of this island, as he stresses the need to ground the upcoming talks in facts and figures rather than emotional reactions. “Yet here in Ireland, where I remember the terrible pages of Sorj Chalandon’s Return to Killybegs, it is difficult not to be touched by the sensitiveness and the emotion of those who share memories reminding me of this tragedy.”

This reference prompts me to reach for my own copy of Return to Killybegs. Just like Barnier, Chalandon was born in the early 1950s. He covered the Troubles as a journalist for French media. His 2011 novel is a fictionalised first-person account of murdered IRA traitor Tyrone Meehan’s life. Its opening page sets the tone: “When my father was drunk, he occupied Ireland just like our enemy did. He was hostile everywhere.”

Growing up in France in the 1990s, my image of Ireland was first structured through distant news reports by the tension between the Peace Process and the last atrocities of the Troubles, culminating in the Omagh bombing. The generation of my parents heard about civil strife in Northern Ireland all their life, with Chalandon and his colleagues conveying decades of horrific news to Barnier back home. This was long before I first set foot here on my Erasmus in 1999. Long before hordes of European tourists descended on the Wild Atlantic Way and Temple Bar, or the French government (of which Barnier is a veteran) felt threatened by Ireland’s tax policy and attractiveness to multinationals.

The Troubles, the Peace Process and the Good Friday Agreement represent most of what Barnier knew about Ireland before he entered the Brexit negotiations. This is his account of how it led to what we now call the Northern Ireland Protocol.

*****

Barnier first mentions the interplay between the Irish border and Brexit in his entry for November 11, 2016. The issue was clearly on his mind before this, including during his first visit as EU chief negotiator to Dublin one month earlier, when it was on the official agenda of a string of meetings with the Irish government. Yet that visit, like most of Barnier’s interactions with the authorities of the Republic, are excluded from his published diary.

For example, he writes later about arriving in the Netherlands from Dublin, without a word about the previous days he spent in Ireland. This is despite his acknowledgement elsewhere that his deputy Sabine Weyand and the member of his team dedicated to Irish issues, Nina Obermaier (both German) maintain daily, close contacts with the Irish Government.

In November 2016, Barnier is sketching out his plan for negotiation with the UK, starting with a Withdrawal Agreement in application of Article 50 of the EU treaty. This is in fact the only legal obligation, though the treaty mentions that the separation terms with an exiting member state are to be set out “taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union”.

This, for Barnier, means two distinct phases of negotiations. Any future trade agreement can come only after the Withdrawal Agreement is sealed. And he lists three things this initial, two-year phase of talks must sort out: the financial settlement of what money is owed under the UK’s existing European commitments; the rights of UK and EU citizens already living in each other’s jurisdiction; and Ireland.

“We must also work on the issue of borders, especially in Ireland, by finding a way of respecting in all its dimensions the commitments of the Good Friday Agreement signed on April 10, 1998 to end the Troubles that tore Northern Ireland apart for 30 years,” Barnier writes.

A few paragraphs later, he adds: “Being the master of time, setting the tempo is key.” The rest of his book – and ongoing wranglings over the Protocol – will show that Barnier’s early inclusion of the Irish border and the Peace Process in the negotiations has been resisted by Brexit supporters from the DUP to Boris Johnson at every turn ever since, for the simple reason that it crystallises the impossible promise they made to their voters during the 2016 referendum that the UK would be both inside and outside the EU in the future.

Soon after Barnier’s 2017 speech before the Oireachtas and a visit to the Monaghan-Armagh border, the snap election lost by Theresa May turns the DUP into an indispensable coalition partner for the Conservative UK government. In his diary, Barnier dismisses commentary assuming he is happy with the weakening in May’s position. On the contrary, he rightly fears this will complicate the talks.

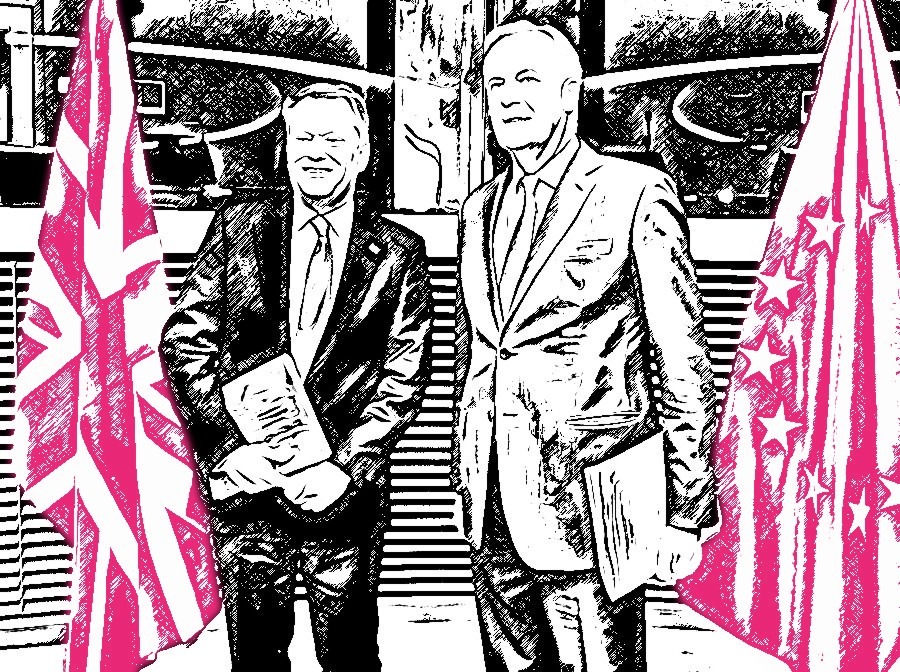

In June 2017, negotiations formally begin between the teams formed by Barnier and his British counterpart, then David Davis. The order and timing of issues to be resolved is the first flashpoint. The UK government wants to talk about the future relationship as soon as possible, leaving more difficult exit questions aside.

At first, the Irish border almost appears as an easy part of the negotiations, compared to the thornier question of payments owed to the EU. “The British clearly have a strategy to push the issues of citizens and Ireland to leave the financial question in the shadows and, as Irish European Affairs Minister Dara Murphy put it to me, purchase pieces of the single market with debts of the past. This strategy, while skilful, is explosive in my view,” Barnier writes. He pushes to resolve financial commitments without delay, while his deputy Sabine Weyand and her UK counterpart Olly Robbins are tasked to specific talks on Ireland.

By September, Barnier has noted little progress when May gives her keynote speech in Florence on what she expects from the ongoing talks. “On Ireland, the Prime Minister confirmed the British government’s commitment to protecting the Good Friday Agreement and its common travel area with the Republic of Ireland, without reinstating infrastructure on the border, which is certainly a step in the right direction, even though she says nothing of the manner in which we will implement the controls needed to protect the single market,” he remarks.

As the end of 2017 approaches, Barnier reports that two of the initial divorce issues, the financial settlement and rights of citizens, are almost resolved. This is when the border begins to emerge as a major problem.

The “Irish trap”

“The issue we are stumbling on is Ireland because it raises passion and sentiment between the Irish and the British,” Barnier worries on November 24. “My strategy has been to make the British acknowledge their responsibility as they exit the EU to maintain north-south co-operation in Ireland, which as been implemented under European law and with EU funding and EU policy support. After they acknowledge their responsibility, if they want to protect the Good Friday Agreement, they will have to provide solutions. And these sector-by-sector solutions essentially consist in what I have called common regulatory areas that would cover the entire island of Ireland.”

As a former minister for agriculture during a French EU presidency, Barnier is familiar with existing cross-border animal health policies. “On a territory as coherent as an island such as Ireland, it is unimaginable to have different regulatory frameworks,” he adds. The idea of the Northern Ireland protocol is now coming to the surface. Yet it is not progressing. On a phone call with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Barnier notes that “she is worried, as I am, about the Irish question”.

His diary entry for December 4, 2017 is titled “The Irish Trap”. On this day, May travels to Brussels to hammer out the joint report expected to contain a final agreement on all points to be legally translated into the Withdrawal Agreement. Both sides have agreed this intermediary step to signal that negotiations on their future relationship can start while the Withdrawal Agreement is formalised. May and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker begin haggling directly on the last details concerning residency oversight for their respective citizens.

“Meanwhile, we feel a certain feverishness on the British side. Several SMSs reach Olly Robbins, who seems put out and passes notes to Theresa May. After the third message, we feel something is happening,” writes Barnier. “She seems nonplussed and does not attempt to hide her disappointment. ‘I have a serious problem with my Irish DUP allies who do not approve of the joint report text on Ireland.’”

It’s unclear whether the qualification of the DUP as “Irish” comes from May or from Barnier’s summation of her words, but the problem remains the same: although the European Commission had received UK approval for the Northern Ireland chapter from Robbins that very morning and from then Taoiseach Leo Varadkar at midday, the DUP is throwing a last-minute spanner in the works. Barnier surveys the wreckage with disbelief: “This point was resolved as far as we were concerned. It is now evident that it is not on the British side, which prevents Theresa May from approving the joint report – ‘if you want to have a British government to talk to,’ she tells us.”

“There is nothing else to do but hope for an agreement between the London Britons and the Belfast Britons.”

Michel Barnier

He goes on to describe the problematic section introducing a double Irish backstop in the Withdrawal Agreement: While the UK government intends to maintain north-south cooperation and avoid a physical border, the agreement would commit it to finding “specific solutions” if any of the 142 existing all-Ireland regulations failed to survive Brexit. And if such solutions are not agreed, then the UK would have to maintain Northern Ireland in full alignment with the rules of the EU common market and customs union to protect the Good Friday Agreement.

“This paragraph, which in fact introduces the option of ‘common regulatory areas’ across the island of Ireland, is the one provoking the ire of Arlene Foster and her friends in the DUP,” Barnier concludes, as May goes home empty-handed. “My team is very disappointed, as I am myself, but there is nothing else to do but hope for an agreement between the London Britons and the Belfast Britons.”

The argument over what is now called the Northern Ireland Protocol has just started. In essence, it has not changed to this day.

Over the following days, negotiators scramble to get the withdrawal phase of the negotiations across the line. Barnier refuses to cede ground on Northern Ireland, accepting only to add reassurances for unionists in the joint report, such as a guarantee that avoiding a hard border in Ireland will also “ensure that no new regulatory barriers develop between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK” unless Stormont agrees.

“The risk we are taking, with lucidity, is that the final text on Ireland becomes a lot less clear and implementable – that such ‘constructive ambiguity’ leaves us with ambiguity only,” he comments.

As the issue is debated in the UK, Barnier notes that the British government begins to consider the option of a UK-wide backstop to avoid a hard border in Ireland. He regards this as “unacceptable”. On December 6, 2017, he writes: “According to comments made by David Davis the day before in the House of Commons, this paragraph introduces the idea that the regulatory alignment with the EU discussed in the context of Northern Ireland could apply to the entire United Kingdom. This brief sentence is another attempt to retain only those parts of the single market they are interested in. More worryingly, the British are trying to use Ireland as a Trojan horse. If this is the case, these talks may as well stop now.”

He doesn’t yet know that they are set to last for another year.

Northern Ireland moves centre stage again in March 2018 when a formal draft of the Withdrawal Agreement is published. Northern politicians visit Brussels and introduce Barnier to their style of politics. First up are Mary Lou McDonald, Michelle O’Neill and Martina Anderson of Sinn Féin. Barnier welcomes their support for the continued participation of Northern Ireland in the EU customs union but refuses to be drawn into their idea of a “special status” for the North. “This won’t stop my visitors, who had purposefully printed ‘special status’ in bold on the documents laid out on the table, to say afterwards that this special status was part of our discussions. On the Irish question, it is difficult to stick with the facts!”

The following day, DUP leader Arlene Foster is next to visit Barnier’s office. “She is accompanied by the Dodds couple: MEP Diane, who is elegant, competent and very active in the agriculture committee of the Parliament, and her husband Nigel, the DUP’s leader in Westminster. There is also Sammy Wilson, renowned for his stormy character, and Nigel Dodds’s assistant Timothy Johnson, who has his feet firmly on the ground.” The phrase in French clearly implies not everyone in the room does.

“Strangely, the first person to speak is not the president of the DUP but Diane Dodds. It is not easy to figure out where the power lies in this party. This is a frank discussion, but Sabine sitting next to me and I have to refocus it on the facts and the truth several times.”

Barnier feels he is under attack from his DUP visitors. In their view, “we would be puppets of the Dublin government, which they loathe, and we would want to create a border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom so that there isn’t one in the middle of the island”. After a stern rebuttal, he reports some degree of thawing when Nigel Dodds acknowledges existing animal health checks between the two islands and they discuss the prospect of similar arrangements in other areas covered by the Good Friday Agreement. “Deep inside, they know it is impossible to have no checks between the north and south of the island, while at the same time having none between the island of Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom.”

The meeting ends with a remark from Foster blaming the lack of a functioning Northern Ireland executive on new unacceptable demands from Sinn Féin. “Yet I know an agreement was found between the two parties two weeks ago and the DUP then went back on its decision,” Barnier comments.

The meeting appears to alienate him from unionist positions, instead comforting him in the romanticised support for the nationalist cause typical of French Gaullists or socialists who lived through the period of the Troubles. (Return to Killybegs, the novel referenced by Barnier at the start of the negotiations, is the sequel to another book by Chalandon, My Traitor. This one tells the story of Tyrone Meehan from the perspective a fictional French regular visitor to Northern Ireland sympathetic with republican positions, not an uncommon approach among this generation.)

After a St Patrick’s Day reception in Brussels, Barnier shares some musings along these lines. “Undoubtedly, I like Ireland and the Irish. The French have always had a particular fondness for this country. It reminds me of the last foreign visit made by General de Gaulle after he resigned the presidency of the Republic,” he writes.

The book is peppered with references to de Gaulle, who took time off in Sneem, Co Kerry to ponder his retirement in 1969. Barnier writes that his personal hero was in tune with Ireland’s culture and landscape and claimed ancestry among the McCartans near Belfast. “For us young Gaullists, it was moving to see this great old man, virtually alone, distance himself from France and political life after losing in the referendum.” The constitutional reform vote was essentially a plebiscite for or against de Gaulle, in which 52 per cent of French people voted No. Although Barnier does not explicitly draw the parallel, the UK’s referendum returned the same result against EU membership.

St Patrick’s week 2018 places Barnier at another function organised by Fine Gael MEP Seán Kelly, where he notes: “One can feel the worry that Brexit might derail the Peace Process and the Good Friday Agreement. Everyone knows that on the other side, in Northern Ireland, there is among the DUP unionists – who never supported the Good Friday Agreement – the thought or afterthought that the march towards the island’s reunification may be stopped, this time thanks to Brexit.”

“There is nothing constructive to expect from this party, which fears a movement towards the reunification of the island.”

Michel Barnier on the DUP

Throughout 2018, as Theresa May’s majority tears itself apart over the realisation of what Brexit actually means, Ireland features more densely in Barnier’s diary. At the end of April, he visits Dundalk where he recalls outlining the EU position before the All-Ireland Civic Dialogue. “The backstop is not intended to move British red lines. It is the consequence of British red lines. As we don’t want a physical border on the island of Ireland, and as the UK has accepted to respect Ireland’s position in the single market, goods entering Northern Ireland, which may then end up in France, Belgium or Poland, must conform with the rules of the single market and the EU customs code,” he explains.

Across the border in Newry, he repeats the exercise with Northern Ireland business leaders, outlining how the “exceptional” admission of the North into the single market implies checks on goods coming from Britain. “Our choice is to explain and de-dramatise this proposal, to strip it of the whole ideological and political dimension that Northern Ireland unionists want to give to it. This is not about questioning the British constitutional order. This is about technical, practical, concrete checks just like existing animal and plant health ones.”

Travelling on to “Derry-Londonderry”, he mentions the 14 victims of Bloody Sunday and reports further reasonable engagement with business people on the protocol solution. “The tragedy is that the DUP, which represents around 30 per cent of Northern Ireland’s voters, holds all other actors hostage as well as the whole British political sphere because its ten MPs give Theresa May the seats she needs to have a majority in the House of Commons. There is nothing constructive to expect from this party, which fears a movement towards the reunification of the island.”

By June 2018, parallel talks are in full swing on the fine print of the Withdrawal Agreement and on the outline of the future relationship to follow after a transition period. Barnier remarks that the British are willing to make progress on a number of issues except one: “The British strategy is clear – isolate the Irish question so that it remains the only one open when the time comes to close the deal in October, hoping that the 27 push it back into the talks on the future relationship. This is precisely what I don’t want. This question is so serious and sensitive for everyone that it must be resolved in the Withdrawal Agreement in any event.”

At that month’s European Council summit, Barnier warns EU heads of government that kicking down Irish border issues into the second phase of talks would risk that “the entire future negotiation is taken hostage over the Irish question”.

In July 2018, Theresa May sets out her hopes for the future relationship with her cabinet gathered at her Chequers country residence, where she decides that the UK as a whole will negotiate to obtain membership of the single market for goods only, removing the need for checks anywhere around Northern Ireland – but also the opportunity to import anything that would not comply with EU laws. Barnier cites American chlorinated chicken as an example. Then Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson is among those who resign and storm out of Chequers in protest.

Meanwhile, Barnier consigns his opposition to the plan in his diary, describing it as “cherrypicking on a grand scale”. For the EU, the single market must remain an entire package if it is to work – and that includes services and labour. On a visit to Washington that months, he shares with views with the Friends of Ireland group in the US Congress.

Dominic Raab, who has taken over the Brexit portfolio after the Chequers purge, makes his first trip to Brussels in August 2018 to push the new UK proposal. Their first meeting is a head-on clash. According to Barnier’s account, Raab says the alternative to the Chequers plan is a no-deal Brexit, leaving the EU to manage the border on its own. Barnier calls his bluff and says that in this case, he will end the negotiation here. “There is a wobble in the British delegation. Dominic Raab realises he has gone too far. Olly Robbins is annoyed. Ambassador Tim Barrow is uncomfortable,” Barnier writes, somewhat self-satisfyingly.

He then reminds Raab of May’s repeated commitment to a backstop solution and steers the discussion towards ways of implementing this, starting with access to data sharing between the EU and the UK on those checks already in place between Britain and Northern Ireland. The same questions come up again at the next meeting between the two men in September – and have remained at the centre of endless technical talks ever since.

“To establish precisely the checks we need for the backstop in Northern Ireland, we must know the volume of trade between Northern Ireland and Britain and the type of goods traded. This is the only way we can detail each necessary check: When, how, where, who? And demonstrate that these technical checks cannot objectively be presented as a border, unlike argued by DUP unionists and other British leaders.” Barnier’s questions three years ago remain the same posed by his successor Maroš Šefčovič today.

“On Ireland, Leo will give us the green light”

At the next European Council summit on September 20, 2018, EU leaders take stock of the laborious negotiations. Barnier quotes Angela Merkel as saying: “On Ireland, I will follow what Leo says.” He adds: “I’m struck by the justified confidence they all have in their colleague, the Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar. ‘On Ireland, Leo will give us the green light,’ several said.”

Varadkar is in Brussels two weeks later to assess progress on backstop negotiations, which have focused on making checks as paperless and decentralised as possible. Barnier describes the then Taoiseach as a “courageous young man”, citing the 8th amendment referendum. He singles out Varadkar’s top diplomatic advisor John Callinan and then Tánaiste Simon Coveney for their role in establishing a “relationship of confidence and friendship” between Government Buildings and the EU’s Brexit task force.

As the withdrawal negotiations enter their endgame, Barnier also meets the leaders of all political parties in Northern Ireland, reserving two hours for Arlene Foster and Diane Dodds. “They don’t like each other, and it shows,” Barnier writes. Despite his annoyance at their competing “slogans” and systematic contrariness, he acknowledges that Foster asks useful questions. “As I listen to these two women, I struggle to remain calm and I wonder whether Theresa May will have the courage and the willpower to resist their injunctions. We will see whether the final Brexit agreement, which they won’t like, will also lead them to collapse the majority.”

Barnier summarises his message to the DUP as follows: “Your vote for Brexit has created the problem. We’re awaiting your ideas and proposals. You’re offering none. When are you going to accept the consequences of your actions?”

As expected, the following weeks are dominated by in-fighting within the British governing coalition with May, the DUP and hard-line Brexiters failing to agree on a format for the Irish backstop. Barnier offers a “two-tier backstop” option, with full alignment with the single market for Northern Ireland and a lighter customs union with the rest of the UK, conditioned to a future trade agreement, and Northern Ireland checks as a last resort only.

The October 2018 European Council earmarked as the deadline to adopt the Withdrawal Agreement comes and goes without a deal. “It is now clear, I tell heads of state or government, that the Irish question is the central topic of this negotiation.”

In the end, the negotiating teams manage to clear the impasse by accepting a light version of the UK-wide backstop, but only as a last resort. “The idea we are working on is that of a customs union which would apply to the entire UK after the transition period if no solution was found to the Northern Ireland problem by then,” Barnier explains.

This level of detail is arcane and now looks less important now that the UK and the EU have struck a wider trade and cooperation agreement. But at the time, the prospect was still uncertain. And each faction supporting May had its own view on which alternative should have priority over another.

On November 14, 2018, May and Juncker sign a Withdrawal Agreement complete with a Northern Ireland Protocol fine-tuned to be acceptable to their respective parliaments – or so they think.

The next day, Raab leads a fresh wave of cabinet resignations. May proves unable to get the deal past the House of Commons and asks the European Council to add a time limitation on the backstop. This would reassure the sceptics in her majority that questions around the Irish border may not restrain the UK’s ability to trade after 2021.

Barnier rejects the suggestion outright. “Then if we failed to find a future agreement avoiding a border on the island of Ireland before that deadline, the arbitration panel provided for in the Withdrawal Agreement could find that the EU is acting in bad faith and allow the UK to suspend some or all of the protocol on Ireland. In this case, the EU would be faced with a choice between two unacceptable options: rush into an agreement assuring frictionless trade, in which case the British would have finally succeeded in taking hostage the whole negotiation on the future relationship by utilising the situation in Ireland; or establishing a physical border on the island on Ireland, with all the consequences we know of in terms of peace between the two communities.”

After EU leaders reject the 2021 deadline idea, May is forced to submit the existing Withdrawal Agreement to the House of Commons, where she is defeated a first time on January 15, 2019.

According to Barnier, the idea of reverting to a Northern Ireland-only backstop and removing the prospect of a UK-wide customs union in the Withdrawal Agreement comes from Irish civil servants. Juncker makes this proposal to May on February 7, 2019. Instead, the British Prime Minister again asks for a time limit on the backstop, which Barnier refuses by saying: “We fear that one day, the United Kingdom will use a backstop deadline in an aggressive manner to put our back up against the wall and force us to accept your Chequers ideas and cherrypicking. We will take no risk with the integrity of the single market.”

Despite additional declarations agreed by both sides to alleviate concerns around the existing Withdrawal Agreement, the House of Commons again rejects it twice in March 2019, triggering an extension of the formal EU exit deadline planned for the end of that month. The new Brexit date is set for October 31, 2019.

The debacle marks the end of Theresa May’s premiership. When Boris Johnson replaces her at No 10 on July 24, Barnier is watching for any signs of his position in Brexit talks. His first statement as Prime Minister is to denounce the Withdrawal Agreement as “unacceptable” until the Irish backstop is fully removed.

“My impression is that the Prime Minister understands, as the discussion develops, a series of technical and legal problems that had not been explained as clearly by his own team.”

Michel Barnier meets Boris Johnson

One month later, Johnson writes a four-page letter to EU President Donald Tusk. “The British government simply demands the abolition of the backstop without offering any other operational legal solution that would solve the problem created by Brexit in Ireland,” Barnier writes. The letter admits that alternative arrangements may not be in place in Northern Ireland by the time the UK exits the EU, which in Barnier’s opinion justifies the backstop in the first place. Instead, Johnson suggests that the problem will be solved if each side unilaterally commits not to erect a border in Ireland.

“This approach is unacceptable under every angle and does not fail to provoke an immediate and unanimous European response to reiterate the aim of the backstop, its necessity and its pragmatic nature,” Barnier writes.

He registers little progress from the first few weeks of exchanges with the UK’s new Brexit Secretary David Frost and understands that the British position is now to keep Northern Ireland out of the single market, and to perform checks away from the border with the Republic – except for animal and plant health which will require stricter scrutiny. How this can be done remains unclear.

“As we end the meeting, Boris Johnson tells us very frankly: ‘I want a deal, I need a deal’.”

Johnson’s first visit to his Irish counterpart Leo Varadkar on September 9, 2019 has been “delayed as much as he could,” Barnier finds. Johnson also makes his way to Brussels one week later for his first direct engagement on Brexit with Juncker.

“My impression is that the Prime Minister understands, as the discussion develops, a series of technical and legal problems that had not been explained as clearly by his own team,” Barnier notes. Johnson wants arrangements for Northern Ireland to be subject to the consent of local politicians, and freedom for the UK to diverge from the EU as long as there is no physical border in Ireland.

“As we end the meeting, Boris Johnson tells us very frankly: ‘I want a deal, I need a deal.’ He now knows the conditions: no customs border in the middle of the island of Ireland and no veto for a single political party in Northern Ireland,” Barnier replies.

The UK follows up with proposals for Northern Ireland to remain partly aligned with EU rules, with checks on goods entering from Britain only. However, Barnier notes that there is nothing on how this will work concretely or affect wider north-south cooperation with the Republic. “Also, all the solutions proposed are conditioned to a positive and unilateral decision by Northern Ireland institutions before they enter into force, and again every four years. This is simply unacceptable. We will not discuss a solution placed under the threat of such a sword of Damocles.”

A walk in the park in Liverpool

Despite this terrible start, Brexit negotiations under Johnson suddenly turn a corner when he meets Varadkar in Liverpool on October 10, 2019 – including during their much-photographed walk down the tree-lined walkways of Thornton Manor.

“According to the Irish government, with whom we had prepared this meeting and who reported to us immediately afterwards, Mr Johnson may now be ready to accept the absence of customs checks on the island, even if this means reinforcing checks between Britain and Northern Ireland. Leo Varadkar, meanwhile, said he was ready to work on a mechanism to reinforce democratic support for our solution,” Barnier recalls.

The proposals open new negotiation fronts. On consent, Barnier warns: “We cannot accept a mechanism that would start implementing the Protocol on condition of the DUP’s agreement and then question its existence every four years”. He also insists any solution included in the Withdrawal Agreement must be fully operational, with nothing left to decide for the joint committee tasked with monitoring it in the future. The current impasse shows that Barnier did not fully succeed on this last point.

The UK’s new Brexit Secretary Steve Barclay agrees to enter a so-called “tunnel” of intense talks on these points on October 11. Five days later, the negotiating teams emerge with the final version of the Northern Ireland Protocol. Checks – and tariffs, if any – are to be imposed on goods entering Northern Ireland from Britain, performed by EU officials and subject to the EU Court’s jurisdiction, except for products that are not at risk of travelling further into the EU. Their list is to be drawn up and maintained by the joint committee.

The agreement is detailed and covers all cases – non-EU goods entering Northern Ireland through Britain, goods manufactured in Northern Ireland for export, etc. “With this solution, we avoid risks to the internal market while respecting the fact that Northern Ireland remains integrally a part of the UK customs territory,” Barnier writes.

On consent, the Protocol will be subject to a vote of the Northern Ireland Assembly after four years. If a majority of MLAs agree, it will apply for another four years – eight if the majority is cross-community. If they don’t, the Protocol will expire after two more years.

After fending off a last-ditch attempt by UK negotiators to introduce VAT exemptions in the Protocol and “create in Northern Ireland a major tax advantage inside the single market,” Barnier can submit the full Withdrawal Agreement to EU leaders at their European Council meeting on October 17. After briefing them on the details of the deal, he writes: “I add that obviously, when talking about Northern Ireland, we talk economy, technical issues, goods, but what has really counted for me over the past three years has been the people of Northern Ireland and Ireland. What really counts is peace.”

For his part, Tusk tells EU heads of government that what really really unlocked the agreement was the Liverpool meeting between Johnson and Varadkar: “This is where Boris Johnson moved on two points: Firstly, by accepting de facto that customs procedures would be implemented around the island, i.e. as goods enter Northern Ireland. Secondly, by renouncing the veto he had imprudently granted in his proposals to a single Northern Ireland party, the DUP.”

The Withdrawal Agreement has yet to go through the House of Commons. To avoid the humiliation suffered by Theresa May one year earlier, Johnson calls – and wins – a snap election on December 12, 2019 on the back of his “oven-ready deal”. The gamble pays off and the DUP is no longer needed to prop up Johnson’s government, which makes its opinion irrelevant to him. On January 23, 2020, the House of Commons finally enshrines the Withdrawal Agreement in British law, in time for the UK to exit the EU on January 31 after a final extension.

From then on, Barnier has what he has always wanted: the Withdrawal Agreement, including the Northern Ireland Protocol, is ratified by both the UK and the EU and has the force of international law. The final part of his book covers the negotiation on the future relationship, which delivered the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement last Christmas.

This second phase illustrates why he was so eager not to leave Irish issues slide into later negotiations. At every turn, the UK continues to use the threat of disorder at the Irish border to strengthen its hand. This starts before the Protocol is even ratified, when Johnson promises on the election campaign trail in December 2019 that there will be no checks between Britain and Northern Ireland. Barnier remarks that this is factually incorrect.

“It is certain that this election has, in the short term, taken from the London government the lever it wanted to have on our negotiation by taking Ireland hostage.”

Michel Barnier on Joe Biden’s victory

The most serious attempt to revive Irish leverage in later trade negotiation is the infamous Internal Market Bill, which the UK government introduces in September 2020 to nullify the Northern Ireland Protocol as a bargaining chip in the wider talks. The scheme collapses when Joe Biden, who has publicly conditioned any US-UK trade deal to the dropping of the bill, is elected US president.

On November 8, the day after Biden’s victory was announced, Barnier writes: “It is certain that this election has, in the short term, taken from the London government the lever it wanted to have on our negotiation by taking Ireland hostage.”

In the end, the UK government withdraws the Internal Market Bill to close the future relationship deal in December. “Michael Gove finally accepts a practical solution so that checks and exchanges in Northern Ireland comply with European law,” Barnier adds – a commitment he was eager to secure before a final trade deal is concluded.

In a final entry added to his diary on February 21 this year, Barnier lists a handful of risks for European leaders to watch in their future dealings with the UK. “First is peace in Ireland, so fragile for 20 years, which remains under threat from the tiniest spark. This is why the European Commission had to correct very quickly the mistake made on January 29 last.”

On that day, Brussels officials concerned with the allocation of Covid-19 vaccines triggered Article 16 of the Protocol, a sort of force majeure clause allowing them to introduce emergency checks on trade between the Republic and Northern Ireland. This was to ensure vaccines made by AstraZeneca in the EU weren’t sneaked into Britain via Northern Ireland while the company failed to deliver contracted volumes.

The clear overreach, although immediately reversed, has given British and unionist leaders a bigger excuse than they could ever have hoped for to perform their own stunts around the Protocol.

“This went frontally against our efforts and responsible attitude during the previous four and a half years, precisely to avoid the return of a hard border down the middle of the island of Ireland, often in the face of British provocations,” Barnier writes. “And these provocations are still going on, unfortunately!”

*****

Barnier’s book helps us understand how the Northern Ireland Protocol came into being and why it remains such a bone of contention with unionists, as well as a useful decoy or bargaining chip whenever the UK government needs one.

Although he gives little away about the Irish influence in this process, it is palpable. Part of it may have played out inside Barnier’s task force, where he acknowledges the contribution of two Irish nationals, press officer Dan Ferrie and energy expert Tadhg O’Briain. A larger role can be attributed to the close cooperation between his team and the Irish government, particularly Simon Coveney and Leo Varadkar.

Barnier is a politician, not a diplomat. His party, Les Républicains, is the French counterpart of Fine Gael and they sit together in the European Parliament’s EPP group. This also applies to Phil Hogan, Ireland’s European Commissioner through the Brexit negotiations, who is credited in Barnier’s book with bringing him to visit food processing factories on the border along with Hogan’s successor Mairead McGuinness as early as May 2017.

The seamless communication between them reached its peak when Varadkar travelled to Liverpool in October 2019 to meet Johnson and clear blockages, leading to an agreement on the Northern Ireland Protocol within days of the trip. We don’t find out which of the two came up with the idea of calling a snap UK election to nullify the DUP’s influence in Westminster, but it had to be part of the plan from then on. Any other scenario would have resulted in the deal sinking in the House of Commons, as experienced by Theresa May one year earlier. This explains the very public grudge held by DUP leaders against Varadkar and Coveney ever since.

Yet the strongest Irish influence on Barnier’s conduct of the Brexit negotiations comes from within himself. In several interviews since the end of his job as EU chief negotiator, he has singled out a meeting with the Northern Ireland Rural Women’s Network in Dungannon as one his strongest memories from the period. The event is mentioned on May 1, 2018 in his diary. “This small town is near the border in the most rural and poorest part of Northern Ireland. Public transport is rare. Each of these women, and some men too, express with simple words what Europe has done for education, social protection, human rights and the environment. Two of them are close to tears: ‘You are our only hope.’” The policies they are talking about have been funded through the EU’s PEACE programme.

Along with his multiple references to de Gaulle and the Troubles, this illustrates Barnier’s genuine fear that Brexit will cause Ireland, or at least its border region, to slide back into a dark past of violence and poverty. The very title of his book is copied on that of Jean Renoir’s film The Grand Illusion depicting the wasted lives of good men sent to World War I by the misplaced nationalistic pride of their governments. “It is also the title of a 1910 essay by Norman Angell, The Great Illusion: A Study of the Relation of Military Power in Nations to their Economic and Social Advantage, in which the English author finds that war is impossible because of the economic and financial ties between nations,” Barnier writes. He adds that, although Angell was proven wrong four years later, he was right in that the war created only losers. Meanwhile, Renoir’s film was released in 1937 as Europe was sliding into a repeat of the tragedy.

In his effort to avoid the same scenario after Brexit in Northern Ireland, Barnier’s book reveals that he is, however, missing one piece of the puzzle: a way into the unionist community and an understanding of its concerns.

To rebalance the typically French, romanticised nationalist views on Ireland that Barnier brought to the negotiation table in his personal baggage, he would have needed regular access to moderate unionists capable of framing their views in a way that could feed into the Brexit talks. There are only two mentions of such constructive meetings in the 546-page book: one with then MEP Jim Nicholson from the UUP, “a man I like because he is sincere”; and one with a delegation from the pro-Brexit European Research Group including David Trimble, with whom Barnier disagrees but enjoys an “interesting” and well-informed debate.

Instead, what he got was multiple confrontational meetings with DUP leaders who pushed him further into the nationalist corner. His accounts of those encounters indicate that Arlene Foster and her front bench had no idea how to approach Barnier and deployed the tactics they normally use on the Stormont boxing ring, expecting them to work in the corridors of technocratic Brussels. As an MEP, Diane Dodds appears to be the only party member who managed to establish some initial connection with the EU chief negotiator, but the relationship quickly floundered.

Barnier returns?

After turning 70 earlier this year, Barnier is showing no sign of retiring. He is currently jockeying for a position in next year’s French presidential race, which will take place during his country’s rotating presidency of the Council of the EU. His prospects seem remote at this point, but so did Emmanuel Macron’s the last time around.

Failing this, a senior EU role would seem logical. In his book, he mentions losing 60-40 to Jean-Claude Juncker in the EPP primary to become president of the European Commission in 2013 and again missing out on the opportunity as he was caught up in Brexit talks five years later. Both the Commission and the European Council will be looking for new presidents in 2024.

Any of these roles would give Barnier significant influence again over the relationship between the UK and the EU, including Ireland. Whenever this may happen, one thing is certain: the aftermath of Brexit and the implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol will still be on the agenda.