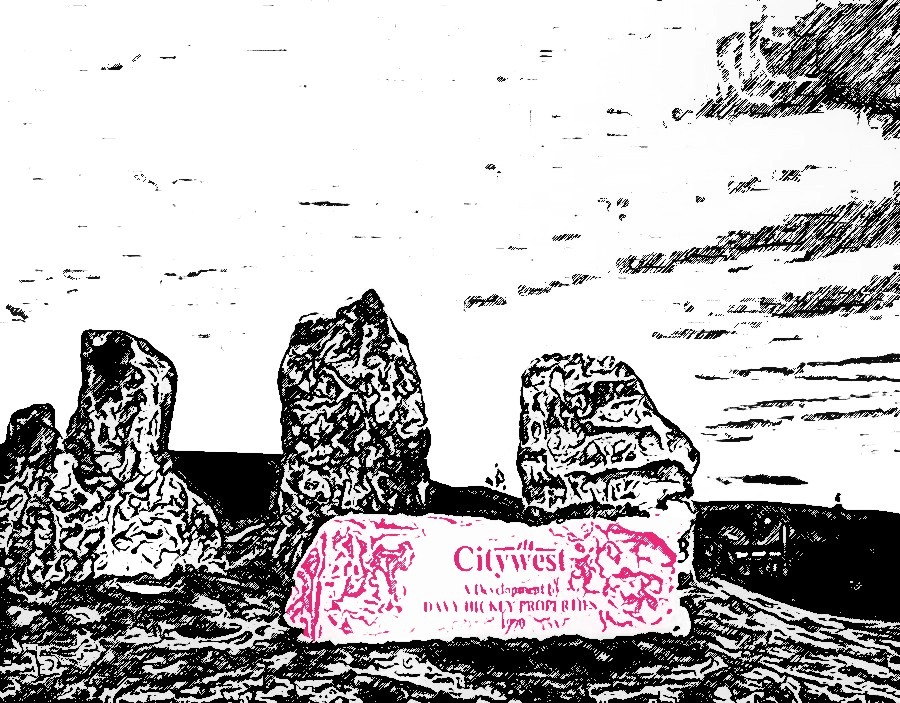

It is a well-worn phrase that when it comes to investments, timing is everything. Property development is no different. It is about good judgement; knowing the risks, the state of the market, the availability of finance, when to buy, when to sell. It is a skillset Citywest developer Davy Hickey Properties (DHP) prides itself on – anticipating market peaks and downturns. Take the 2008 economic crisis. Whether it was business acumen, luck, or a combination of the two, DHP came through the dark years bruised but unbroken having fortuitously shed a significant chunk of its portfolio on the precipice of…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to continue reading?

Introductory offer: Sign up today and pay €200 for an annual membership, a saving of €50.