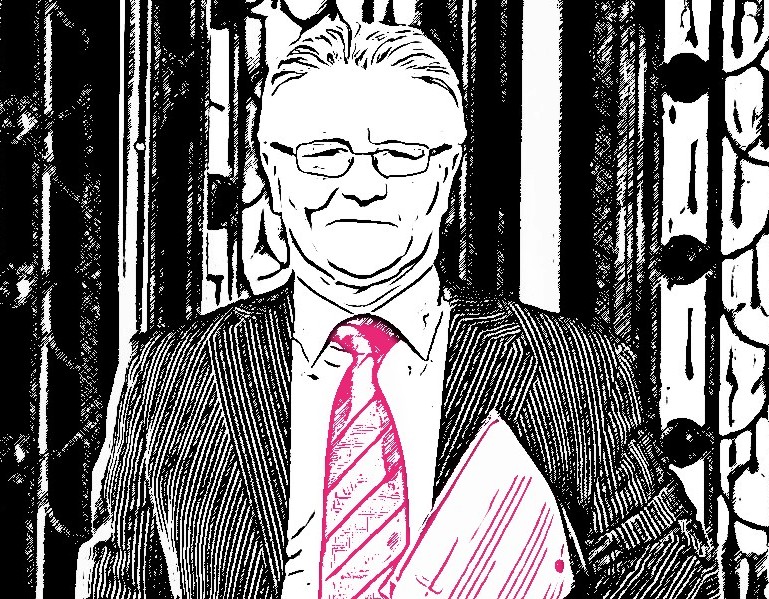

The property developer Patrick Kearney has filed a statement of claim in the High Court detailing his case against the stockbroker Davy and 16 of its former employees. The 25-page document details what Kearney believes occurred in relation to the Davy bond scandal, a controversy that resulted in a Central Bank rebuke and fine, triggering a decision by the company to put itself up for sale. Kearney has appointed barristers Martin Hayden and Eamon Marray and law firm Clark Hill to represent him in the action, a case that both the stockbroker and the 16 former employees say they intend…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to continue reading?

Introductory offer: Sign up today and pay €200 for an annual membership, a saving of €50.