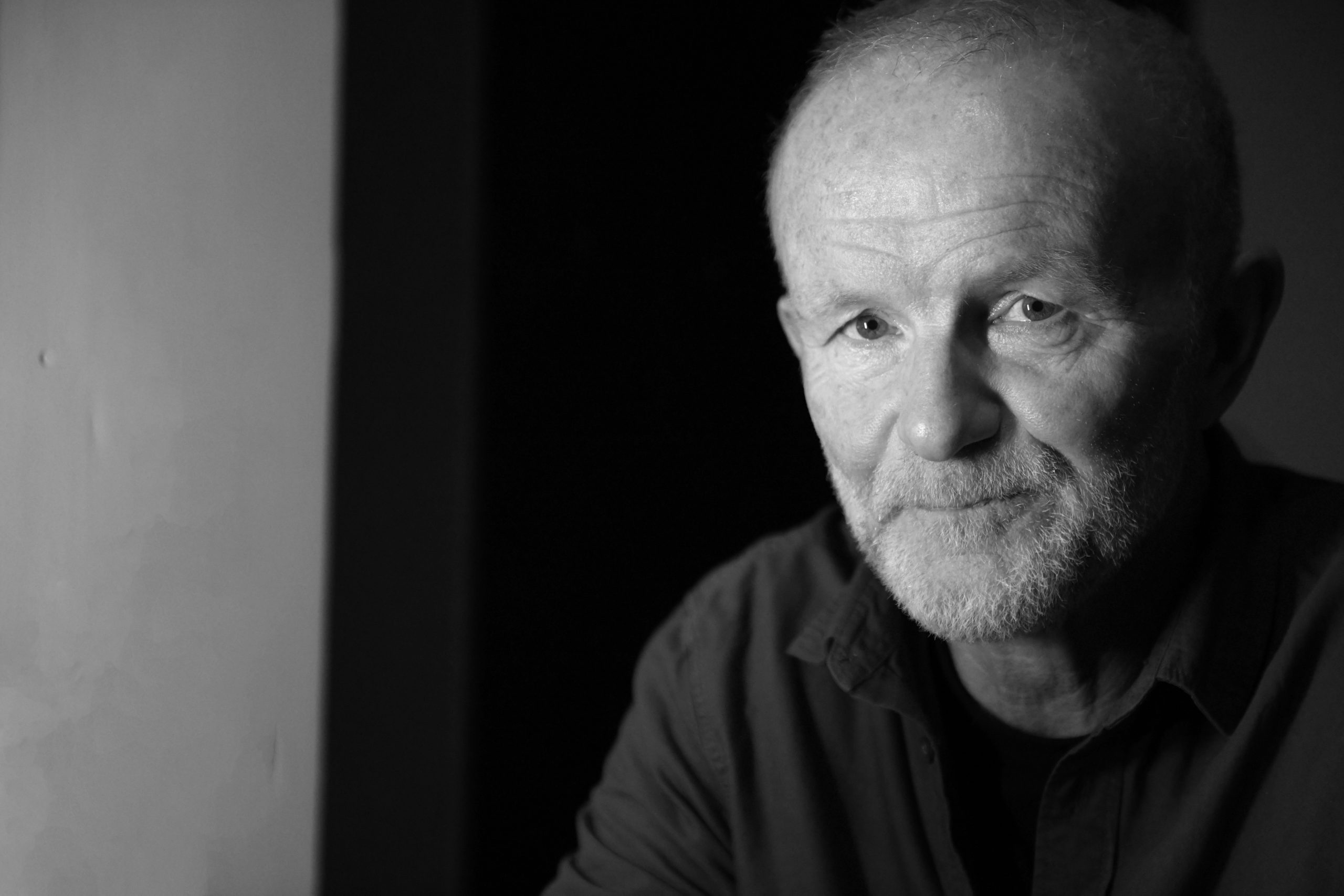

“There have been too many things that troubled me and continue to trouble me for the self examination that is part of the book not to incorporate a degree of angst.” Fintan Drury was an acclaimed journalist – presenting Morning Ireland in his 20s – before starting another successful career in business but the success – and the failures – came at a cost. His book which has just been published, See-Saw, is subtitled -A Perspective on Success, Leadership and Corporate Culture. It provides that perspective, but it also portrays a man, as he acknowledged in this podcast, who has…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to continue reading?

Introductory offer: Sign up today and pay €200 for an annual membership, a saving of €50.