As employees walk the multicolour-lighted concourse connecting three of the buildings forming part of Google’s headquarters for Europe, the Middle East and Africa across Dublin’s Barrow St, cranes can be seen on the site of the internet giant’s 13-storey extension under construction at the old Boland’s Mills, a short distance away along Grand Canal Dock.

Down at street level, the technology behind electronic access control points does not seem to have earned the management’s trust – three security guards in high-vis check the comings and goings at each of the complex’s gates.

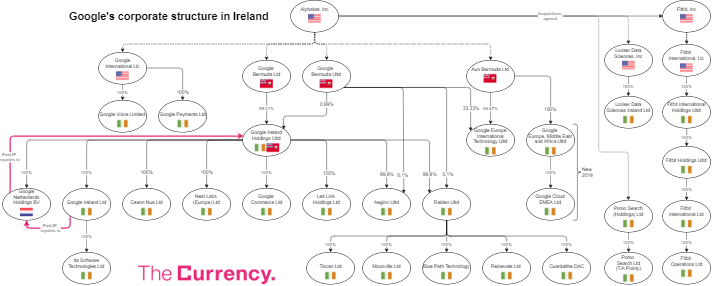

Google’s 19 subsidiaries in the Silicon Docks (click image below to enlarge), ultimately held by the group’s US parent Alphabet, Inc through various American and offshore holding structures, are now being joined by Fitbit’s cascade of Irish entities following the acquisition of the fitness wearables manufacturer.

The December publication of accounts for the group’s main Irish-registered holding entity, Google Ireland Holdings Unlimited, marked the end of the 2018 results season for Irish subsidiaries of technology multinationals. Over the coming weeks, The Currency will crunch the numbers and enlist the experts to examine how key companies, and the sector as a whole, has evolved in recent years marked by unabated growth and shifting international tax rules.

8,000 staff… or 3,500?

In the absence of consolidated filings for Ireland, Google’s customer-facing subsidiaries here totalled nearly €40 billion in revenues in 2018. The bulk of this came from Google Ireland Ltd, which sold €38 billion worth of advertising space to customers in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. It was also the group’s only Irish subsidiary to report employing any staff, with 3,579 employees in 2018.

Although this number is likely out of date (Google’s global workforce increased by 15 per cent over the first nine months of last year, according to Alphabet filings), it is strikingly lower than the 8,000 staff currently claimed by the IDA on behalf of Google in Ireland. This would leave around half of the group’s workers as indirectly employed contractors, while the average salary of €104,000 in 2018 (or more than €150,000 including benefits and employer’s PRSI) applies only to Google Ireland’s direct employees.

Another €1.3 billion in revenue was generated by Google Commerce Ltd through sales on the Play Store platform. In total, Google’s Irish trading subsidiaries posted just under €2 billion in pre-tax profit and paid €540 million in corporation tax.

By contrast, its two main Irish-registered holding companies, Google Ireland Holdings Unlimited Company and Google Europe International Technology Unlimited Company, which charge other group entities for use of intellectual property, had a combined $28.4 billion in revenues and $17.6 billion in profits. They paid no income tax and sent more than $26 billion worth of dividends and distributions to their overseas parents in 2018, an eight-fold increase on the previous year. Filings from the two companies show that their combined interim dividends and distributions again increased to over $28 billion in 2019, with a final figure yet to be published.

Google Ireland Holdings revealed in its December filing that it would also dispose of liquid debt used until now to park cash in Ireland: “The Company will no longer invest in or hold debt security investments. When instructed by its immediate parent the Company will distribute the majority of its debt security investments at fair value at that date, along with its intangible assets and certain equity investments at carrying value to its immediate parent.”

At the end of 2018, Google Ireland Holdings held $43.8 billion worth of such “marketable securities” including US government bonds, corporate bonds and mortgage-backed securities (down from $55.7 billion one year earlier). These accounted for the majority of the $63.1 billion in shareholders’ funds held by the group’s two top holding entities here.

Over the past two years, Google’s repatriations reported so far have been equivalent to €48 billion. They follow a change in US tax rules introduced by President Donald Trump’s administration in December 2017, which imposed a once-off tax liability on profits accumulated abroad by American multinationals, and previously shielded from tax until parent companies brought the funds back home. “These are to be taxed at a rate of 15.5 per cent for cash and 8 per cent for investments in illiquid assets whether or not the funds are repatriated to the US,” Trinity Business School professor of international business and development Frank Barry explained in a paper in the Economic and Social Review last June. This is in contrast to the regular US federal corporation tax of 21 per cent, reduced from 35 per cent by the same Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

“The big question, in Google’s case, is what structure is replacing the Double Irish?”

Gabriel Zucman

In 2019, Google decided to move large assets out of Google Ireland Holdings, which is domiciled in Bermuda and therefore income tax-exempt. Its directors reported in December: “A decision was made by senior leadership of Alphabet Inc. to reduce certain functions provided by the Company. As part of this decision, the Company will cease to license intellectual property to a subsidiary undertaking and as a result the Company’s turnover and associated expense base derived from licensing activities will cease.”

Gabriel Zucman, an associate professor of economics at UC Berkeley who has written extensively on cross-border taxation issues, told The Currency: “The move of Google’s IP probably reflects the phasing out of the Double-Irish arrangement, which allowed Google to shift profits tax-free to Bermuda for many years. The big question, in Google’s case, is what structure is replacing the Double Irish?”

This year marks the end of the infamous scheme, under which intellectual property held by a non-resident, tax exempt Irish company could be licensed to another, tax-resident one with royalties offset against taxable income. “As the Netherlands traditionally did not impose withholding tax, while Ireland did not impose withholding taxes on intra-EU transfers, profits frequently transited through the Netherlands on their way from Ireland to the micro States,” Barry added, taking Google as an example of the tactic with Bermuda the destination of extracted funds. While then Minister for Finance Michael Noonan closed the Double Irish in Budget 2015, this only takes effect in 2020.

Dutch sandwich via Singapore

On New Year’s Eve, Google Netherlands Holdings BV, an Amsterdam-based subsidiary of Google Ireland Holdings, announced a similar move away from IP licencing in its annual accounts, effective “as of 31 December 2019 or during 2020”. This company provided the proverbial Dutch sandwich in the Double Irish tax scheme. In 2018, Google Netherlands Holdings received €16.1 billion in royalties from the trading company Google Ireland, and another €5.7 billion from Singapore-based Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd. The Dutch entity in turn paid the corresponding €21.8 billion to Google Ireland Holdings. Its income tax bill that year was €3.5 million.

As part of the IP restructuring, Google Ireland Holdings received unspecified “intangible assets” from one of its subsidiaries in October and immediately passed it on to its parent outside Ireland, while waiving an intercompany loan worth $1.4 billion. IP formerly licensed through the Double Irish is expected to be transferred to the US, but Google and Alphabet have not replied to queries from The Currency seeking further details on the new arrangements.

Brad Setser, an economist at the New-York based Council on Foreign Relations specialising in cross-border flows, told The Currency that Google appeared to be taking advantage of another aspect of Trump’s 2017 US reform – the lower tax rate offered on foreign-derived intangible income (FDII). “That’s the key thing with the end of the subsidiary that had the R&D cost share and thus got the IP licensing,” he said – adding, like Zucman, that things would become clearer if Google confirmed a new US-based structure for these assets.

While a number of multinationals have recently chosen to base more IP in Ireland as the tax net tightened on structures extracting royalty revenue to offshore destinations with no real operations, Google’s apparent choice to move it back to the US under the FDII scheme instead could be an outlier.

“When the choice is solely between an Irish and a US location, the tax liability is almost exactly the same.”

Frank Barry

According to Barry, the scheme’s reduced effective tax rate of 13.1 per cent, combined with other measures in the 2017 US reform, leave it very close to Ireland’s existing 12.5 per cent rate. In terms of locating IP assets for sales outside the US, which is what Google does in Ireland, Barry wrote: “When the choice is solely between an Irish and a US location, the tax liability is almost exactly the same.”

He added that FDII lacked cross-partisan support when it was introduced in the US and ran the risk of being struck down by the World Trade Organisation as an illegal form of export subsidy. “This uncertainty can be expected to dampen any short-term response,” Barry concluded. Google has seen things differently.

Looker and Pointy acquisitions

More changes may be afoot in the corporate structure of Google in Ireland: between September and November 2019, the group registered two new companies in Dublin. Google Europe, Middle East and Africa Ltd is directly held by AUN Bermuda Ltd, one of the group’s offshore entities, and in turn owns Google Cloud EMEA Ltd.

Last June, Google also agreed to acquire Looker for $2.6 billion, which means the 22 people employed by the US data analytics company in 2018 at a WeWork office in Dublin may find a new home in the docks. The deal is currently being examined by the British competition watchdog.

While Looker’s Irish subsidiary was profitable in 2018 and had €8.4 million in turnover, this arose entirely from the sale of business services to its ultimate US parent company.

On Tuesday, Irish start-up Pointy’s directors Mark Cummins and Charles Bibby announced that they, too, had sold their company to Google. TechCrunch reported the deal to be worth €147 million.

The company founded in 2014 in Dublin allows bricks-and-mortar retailers to advertise their products online simply. It was employing 33 people on Amiens St at the end of 2018 and had yet to return a profit.

Read The Currency this Friday for more on the Pointy deal.

Fitbit’s intellectual property in the balance

On 3 January, Fitbit’s shareholders accepted Google’s November offer to buy their company in a deal valuing the fitness wearables manufacturer at $2.1 billion. The acquisition will bring Fitbit’s four Irish Russian-doll companies into Google’s fold, along with the 58 people it employed on Dublin’s Baggot St in 2018.

That year, Dublin-based Fitbit International Ltd recorded just under $500 million in sales. In addition to its own non-US markets, this and two other Irish entities hold the group’s subsidiaries across Europe, in Singapore and in Hong Kong.

Fitbit International Ltd acquired intellectual property rights from its immediate Irish parent in November 2018, valuing them at $346 million. Both companies were loss-making that year. “The company has the rights to a licence to utilise another group company’s intellectual property in the design, development, manufacture, marketing, distribution and support of the Fitbit products in all territories outside the Americas,” directors for Fitbit International Ltd reported.

The decision to maintain Fitbit’s international intellectual property assets in Ireland at the time may be at odds with the strategy of its new owners, following Google’s recent announcement that it was instead moving IP out of this country.