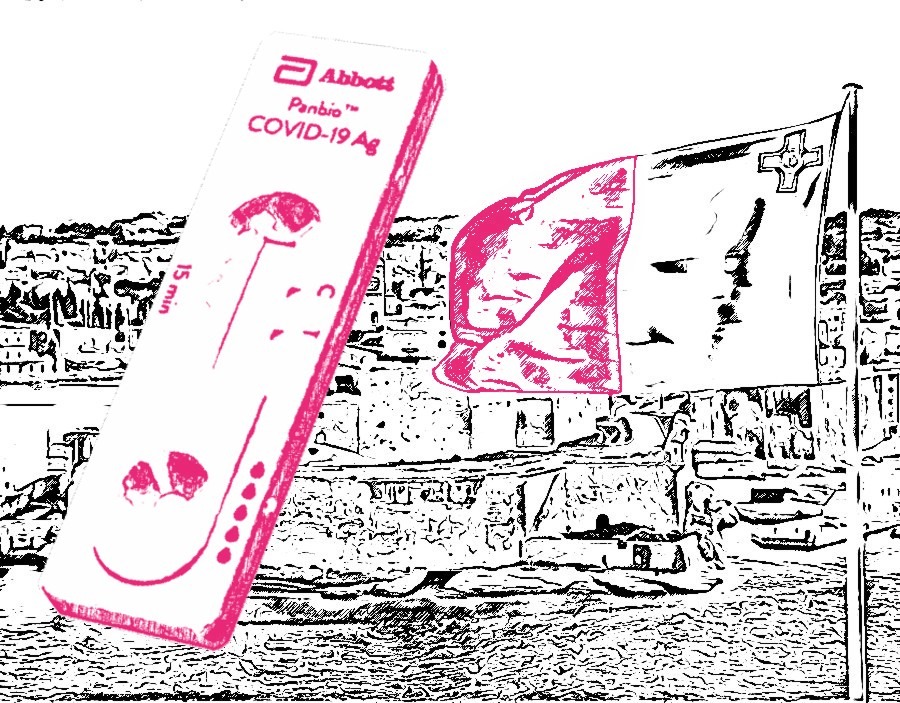

The starting point of this investigation is a US-headquartered group of companies reporting over €1 billion in worldwide sales of Covid-19 and other rapid diagnostics tests out of Ireland, with nearly half of this amount emerging as profit in another country where it is subject to a much lower tax rate than here. Sounds familiar? For over 30 years, US-headquartered multinationals used the infamous double Irish corporate structure to book international sales of products and services in Ireland. The portion of American technology and brands underpinning those revenues was placed in separate companies incorporated in Ireland but domiciled offshore in…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to read the full story?

Unlock this article – and everything else on The Currency – with an annual membership and receive a free Samsonite Upscape suitcase, retailing at €235, delivered to your door.