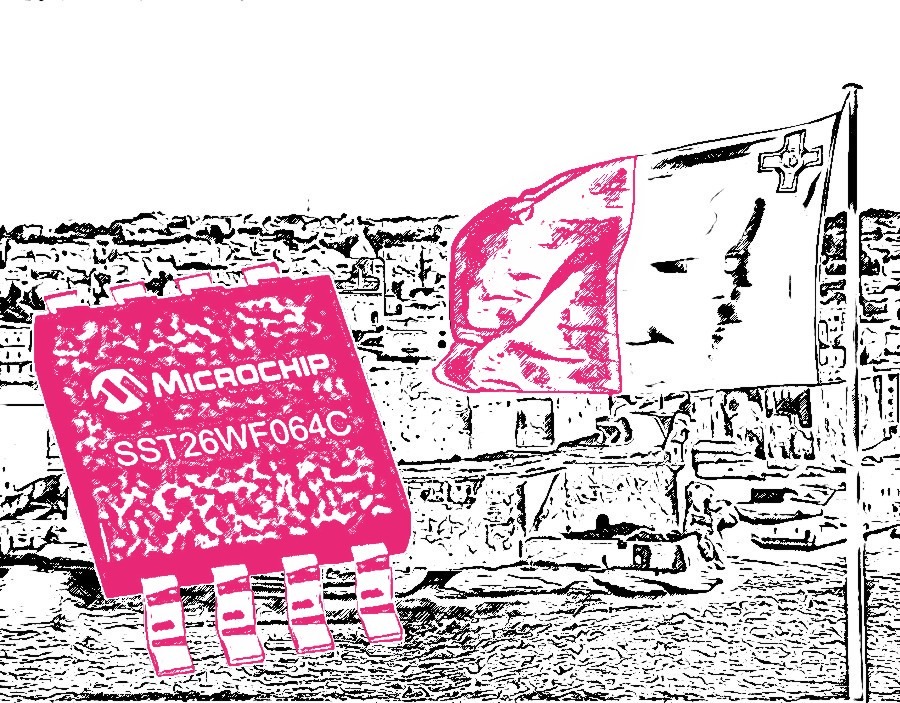

Over the past two days, The Currency has revealed how the US-headquartered pharma giant Abbott Laboratories squeezed through the loopholes left open by changes in tax rules intended to shut down the so-called double Irish and single malt schemes. The group routed international sales of Covid-19 and other rapid diagnostics tests through Ireland, while corresponding profits emerged in Irish-incorporated companies holding intellectual property under tax residency in Malta, where they achieved a 4 per cent corporation tax rate in 2020. Abbott, however, is not the only multinational using Ireland as a base to minimise its tax bill through what could…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to continue reading?

Introductory offer: Sign up today and pay €200 for an annual membership, a saving of €50.