The CEOs of most publicly listed companies have only one job: Make the share price go up.

It’s not an easy job. But it is at least straightforward.

It’s called the shareholder value theory of corporate governance. It became dominant in the 1980s. And it says the only moral responsibility of a corporation is to its shareholders.

Before the 1980s, things were murkier. Companies were run less in the interests of shareholders and more in the interests of managers, employees, suppliers, and the wider community. For better or worse, those times are gone.

AIB’s CEO Colin Hunt made a mistake this week when he approved the removal of cash services from 70 of AIB’s branches, mainly in rural areas.

He thought he was the CEO of a normal public company, whose sole responsibility was to the shareholders.

But he learned that AIB isn’t a normal company. It has obligations to more than its shareholders.

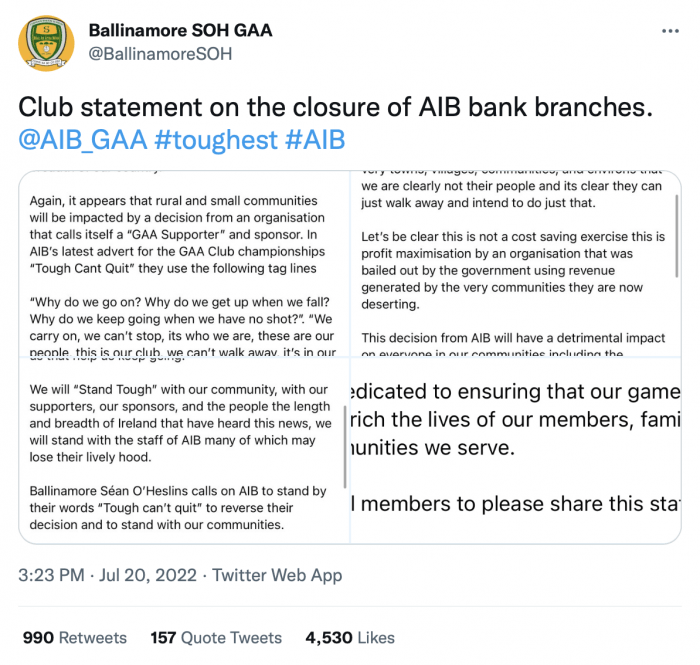

An early sign AIB’s decision hadn’t gone down well was a statement, tweeted out by Leitrim’s Ballinamore Sean O’Heslin’s GAA club, which had more than 1,100 retweets and 4,500 likes. The statement said:

“It’s clear from the decision made by AIB to close 70 branches, a decision which will impact communities with upwards of 350 GAA clubs that operate in those very towns, villages, communities, and environs that we are clearly not their people and its clear they can just walk away and intend to do just that.”

Ballinamore’s statement caught the public mood (though to be fair, AIB wasn’t planning to close branches). The story grew legs. By Friday afternoon, a delegation of rural TDs — Mattie McGrath, Michael Collins and Danny Healy-ae — were headed for AIB headquarters to make their feelings known. On Friday, the story led the morning news bulletins and was all over talk radio.

By lunchtime on Friday, little more than three days after the initial announcement, AIB got the message and reversed course. The 70 branches will retain cash services.

Colin Hunt made the mistake of acting like the CEO of a normal listed company responsible only to his shareholders.

The shareholders want AIB to cut costs. AIB’s cost-to-income ratio — the key metric for a bank’s operational efficiency — was 64 per cent last year. Lean, efficient banks, like those in the Nordics, have a cost-to-income ratio of 55 per cent or lower. Bank of Ireland, which has been more aggressive in cost-cutting to date, has a cost-to-income ratio of 58 per cent. By contrast, Finance Ireland, the non-bank lender that was valued earlier this month at €250 million, has a cost-to-income ratio of 48 per cent.

Whenever AIB reports its earnings to the stock market, Hunt takes questions from bank analysts over AIB’s elevated costs. That’s why in 2020, AIB promised the market it would cut €230 million in costs by 2023. A survey by Autonomous Research, a data provider, found AIB was ranked 48th out of 56 banks for the proportion of its branches it had closed since 2007.

And then there’s the regulator. AIB is regulated by the ECB, via the EBA, via the Central Bank of Ireland. The ECB knows European banks are chronically unprofitable. It doesn’t want to relax the limits on risk-taking it imposed after the financial crisis. So the ECB’s solution to bank unprofitability is to encourage consolidation among banks. It has said Europe is “overbanked”. (Consolidation, to be clear, typically involves merging companies, closing duplicated functions and cutting staff.)

Here in Ireland, the former head regulator at the Central Bank of Ireland, Ed Sibley, told Sean in an interview last year that the reason Irish banks were unprofitable was that they have “legacy issues, underinvestment in IT, [and a] high cost base”.

So AIB’s regulator, as well as its shareholders, is telling it to cut costs. For a normal company, it would be an easy decision.

But AIB isn’t a normal company — normal companies aren’t 68 per cent owned by the state. And of course the story of how AIB came to be 68 per cent owned by the state is a big factor.

Ireland’s rural communities are vulnerable. That’s why there has been such a strong backlash to this decision. Rural communities fear the loss of cash services at their local bank branches will be another hammer blow to the local economy. And they think, after all the public money pumped into AIB, that it should treat their communities better than this.

It’s a difficult decision for Colin Hunt, as we’ve seen, and it’s difficult for the government too. Many TDs’ job is to fight for rural communities. But AIB is a national asset, guarded over by the Minister for Finance. It’s currently worth €5.8 billion, but not least because of its high costs, the share is underperforming. The hope is that AIB can fix its problems and be sold on the market for something close to its book value. That would value it at about €11 billion. The state’s share of that would be €7.4 billion.

The worry for the Department of Finance is that the management of AIB gets contaminated by electoral politics, as it seems happened this week. That the share prices takes on a new political risk discount. And that we either don’t end up selling the bank (because it’s not viable on its own) or we end up selling it for billions less than we’d hoped for.

It’s not a trivial concern. Interest rates are rising. Higher rates will severely stress household budgets. As Stephen wrote in his piece this week, “the politics of stagflation, where the gains of low levels of economic growth are washed away by rising inflation, are truly toxic”.

The banks will be blamed for much of this. Will the government let them pass higher interest rates onto their customers? Should they?

Elsewhere this week

Rosanna investigated the working conditions for migrant fishers. Fishers tend to exist on the furthest fringes of society, as most of their work takes place many hours from the shore. Protecting their employment rights is proving to be a challenge.

An actor famous in France (or so I’m told by Thomas) named Dany Boon began holidaying in West Cork. He fell in with a Frenchman called Terry Birles, who told him he was an Irish lord and maritime expert. Now Boon is suing Birles, alleging he defrauded him out of between €4.5 and €6.7 million.

My investigation of a controversial tax strategy shows that Irish pensions — €162 million worth over ten years — are being transferred to Malta. Revenue say the tax-efficient Maltese structures are “opaque” and “risky”.