Having overseen the loss of $8 billion so far on Disney+, Disney’s CEO Bob Chapek got sacked this week.

Chapek had associated himself with Disney+, which is Disney’s expensive plan to sell its films directly to consumers.

But the wind has changed. All of a sudden, companies are changing tack and they’re focused on profits. Loss-making, risky, long-term projects like Disney+ look much less attractive than they did two years ago.

If companies are only now focusing on profits, it begs the question — what were they doing before now?

The rise of superstars

What was going on was that technology firms, generously backed by investors, were grabbing as much market share as possible. Having established themselves, the idea was that they’d make money later on.

The plan was dependent on cheap capital, and it didn’t work out for a lot of companies, but it wasn’t stupid. In the last twenty years, there’s been a huge opportunity for companies bold enough to burn through a few billion of investors’ money.

In the 2010s, researchers noticed something odd in the productivity statistics. They saw that productivity growth, instead of being broadly shared, was concentrated in a small number of companies. These companies they termed superstars.

Superstar firms have been responsible for an outsized share of productivity growth and corporate profits since the 1990s. They squeeze out competitors, resulting in more concentrated markets. They absorb a greater share of profits, relative to workers. And they are found all over the world, not just in one or two markets.

When you picture a superstar firm, you’re probably thinking of a technology giant like Alphabet or Apple. And they are indeed superstars. But superstar isn’t a synonym for tech. What Autor et al found in a 2020 paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics is that, across industries, superstar firms are pulling away from the rest. They’re making more money, with wider margins, paying greater returns to shareholders and pushing out competitors.

The following chart from Autor et al shows how, in six industries, the top firms by sales had an outsized lead in terms of productivity.

Superstar firms have been responsible for an outsized share of productivity growth and corporate profits since the 1990s. They squeeze out competitors, resulting in more concentrated markets. They absorb a greater share of profits, relative to workers. And they are found all over the world, not just in one or two markets.

Looking at a company like Uber, Deliveroo or Disney from the outside, it’s reasonable to ask what they’re playing at. For years, Uber lost money on every journey. Disney+ is losing money on every subscriber. Amazon’s Alexa speaker division, we learned this week, is on track to lose $10 billion this year. What all these companies have been trying to do — in industries from food delivery to taxis and personal speakers — is trying to establish themselves as superstars.

We’ve been living with superstar firms for the last twenty years, so we’re used to them, but they are weird. This is not how capitalism is meant to work. The biggest firms aren’t meant to get bigger and richer indefinitely.

In a recent note, Michael Mauboussin quoted the economist George Stigler “There is no more important proposition in economic theory than that, under competition, the rate of return on investment tends towards equality in all industries.”

What’s going on? It definitely has something to do with software. Looking at superstar firms’ accounts, what you see is lots of investment in intangible assets.

In a 2020 paper for the US National Bureau of Economic Research, Brynjolfsson et al found “digital capital has disproportionately accumulated in a small subset of “superstar” firms and its concentration is much greater than the concentration of other assets, and 4) that digital capital accumulation predicts firm-level productivity about three years in the future.”

Software lets big companies do things they previously couldn’t do. They can manage their operations better and be more agile. Walmart is an example of a company that, in the 1990s, made better use of software to take over the US retail industry.

For investors, the problem is that it’s hard to pick a winner in advance. The company with the biggest market share in the early years of an industry isn’t the one that’ll eventually become a superstar.

Don’t come second

There’s a concept of minimum efficient scale — the level of output at which a company hits its level of long-run average costs. If you think of a hairdresser, average costs probably flatten out after the first couple of salons. So a couple of salons is the minimum efficient scale. But a manufacturer of aeroplanes needs to be producing thousands of planes per year before its average costs flatten out.

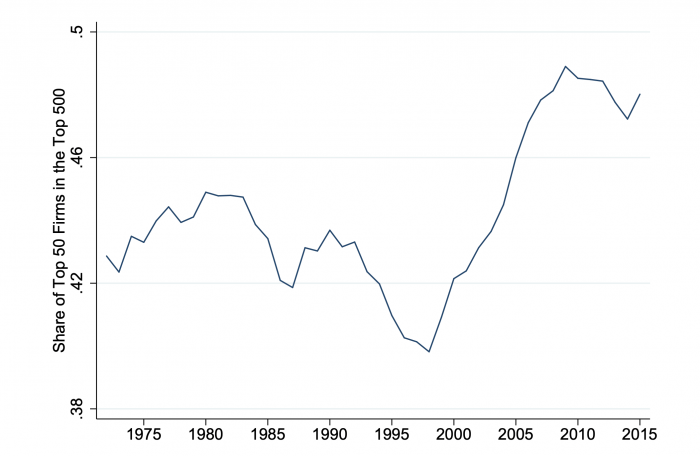

All this investment by superstar firms in proprietary software systems and other intangibles has increased the minimum efficient scale of these industries, said Michael Mauboussin in a recent note. The following chart, from Autor et al, shows the share of sales of the biggest 50 companies as a share of the sales of the biggest 500.

For investors, the implication is that the prize is bigger for backing the superstar firms. So it makes sense to back them heavily. By being conservative with their capital, investors risk backing an also-ran company whose destiny is to be squashed by a superstar.