One of the punchlines in my big piece on DCC is that it’s less heavily indebted than other companies in its industry.

That was also a takeaway from a story I did last summer on the indebtedness of corporate Ireland.

I started work on that piece with the expectation that I would find lots of Irish companies with uncomfortably high debt levels; companies at risk of bankruptcy as interest rates started to rise.

Sadly for my piece — but happily for corporate Ireland, in this instance — what I found was that Irish companies in general are very conservative with debt. They use much less than peer companies in the same industry in the US, for example.

Why that is, we can only guess. The global financial crisis might have scarred a generation of CFOs. Or the global financial crisis might have stopped banks from lending freely.

Or it might be that, after four decades of shareholder value theory, and prowling private equity firms, US companies have fully internalised the lesson that shareholder value is the name of the game. And debt is a big part of that. Debt can amplify returns to shareholders. It also helps to keep unwanted buyers at bay.

How does debt help shareholders? Companies need money to fund themselves and there are only two ways they can get it: equity investors (who get a share of profits) or debt investors (who get a fixed income stream).

Debt investing is less risky than equity investing because, if the company goes bust, they're ahead of equity investors in the queue to get whatever's left over. Equity investors come last. Equity investors have more downside risk but also more upside potential.

Because debt investing is less risky than equity investing, debt investors demand smaller returns. Where an equity investor might demand 10 per cent, a debt investor might be happy with 3.5 per cent.

That, in a nutshell, is why it makes sense for businesses to borrow money: because debt investors expect a lower return than equity investors. Borrowing money means more money is left over for equity.

A company that's funded solely by equity is funded solely by people who demand a 10 per cent return on their money (for example). Better to get rid of some of them, and replace them with people who'd happily take a three per cent return.

Doing this would result in less profit because there would be interest bills to pay. But the profit would be divided up among a smaller number of shareholders, hopefully resulting in greater returns.

Of course, this logic has a limit — there's only so much debt a company can safely borrow. The more a company borrows, the higher the risk of bankruptcy. The first euro of debt is safe, and it doesn't make the company much more risky. But the more that gets added, the greater the risk of bankruptcy, the riskier the company becomes, and the greater the return that investors (both debt and equity) will demand.

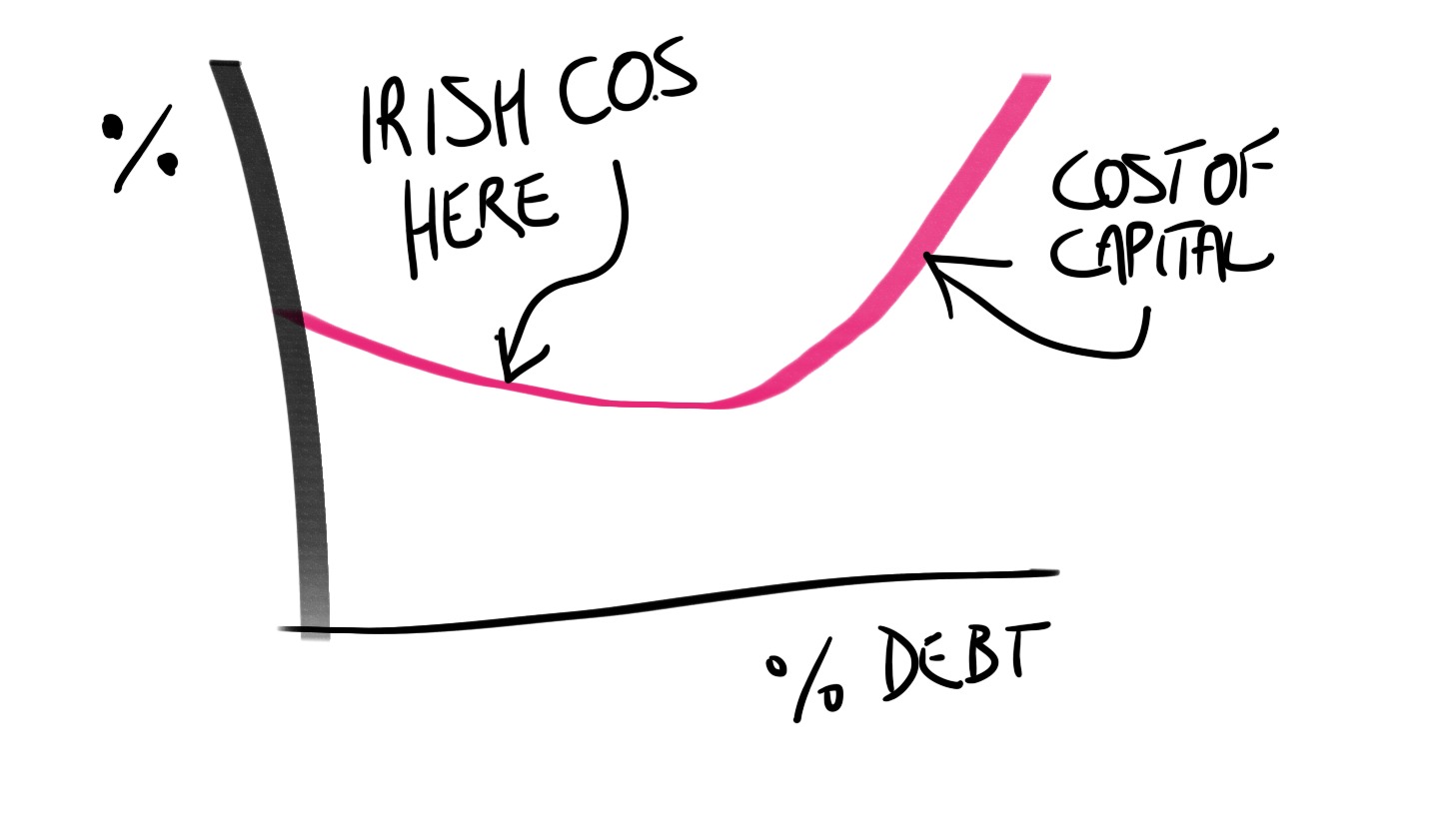

So debt funding starts off cheaper than equity funding. But the more you add, the more expensive it gets.

For every company, there's a sweet spot: where either reducing or increasing the amount of debt will increase the company's overall funding cost (what's called the weighted average cost of capital). The optimal amount of debt is the amount that minimises this number.

The number is different for every company, and it basically depends on how risky the business is. Risky businesses can't get away with much debt. Safe businesses can get away with a lot. Biotech startups don't use any debt; regulated water utilities use a lot of it.

What's meant by risky? Anything that would mean the company doesn't have enough to cover its interest payments in a given year. Once a company misses an interest payment it's game over for shareholders, and the lenders (usually) get to come in and take the business over.

There are ultimately only two sources of risk: the amount by which revenue fluctuates from year to year, and the size of fixed costs as a percentage of total costs. A company with unstable revenue is obviously going to have unstable profits. High fixed costs mean small changes in revenue translate to big changes in profits.

By using less debt than their US cousins, Irish companies are leaving money on the table. They are saying they prefer stability to returns. Given the turmoil of the last few years, they might say they're happy with that decision. But to be fair, it's not as though more-indebted corporate America fell to pieces because of Covid-19 or rising rates.

This must be part of the reason private equity is on the rise in Ireland — what private equity is good at is finding under-levered companies, having the companies borrow a lot of money, and using it to pay themselves a big dividend.

If it is the case that Irish companies are choosing to borrow less than they could (and not having that decision forced on them by lenders), it's good news for the country. It means there are investors sitting on the sideline, ready and willing to fund new projects and companies and to put people to work. I hope that's what's going on.