At a conference last week, I saw the Irish policy establishment forming a consensus on an important matter of state.

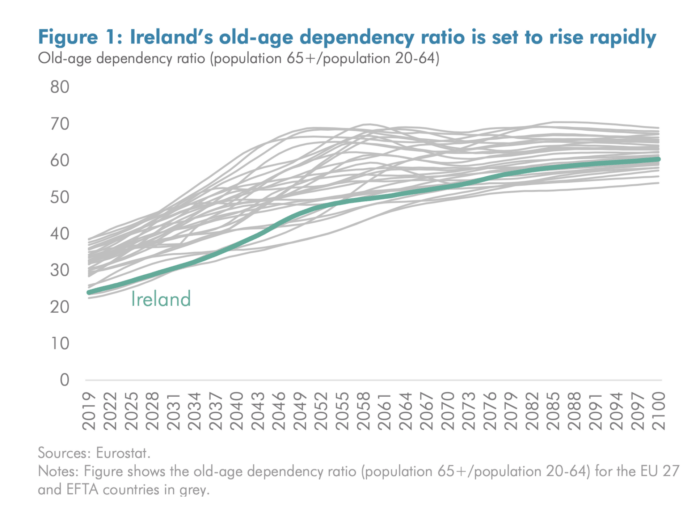

The problem is Ireland’s demographics: by 2050, the ratio of retired people to workers will be more than double what it is today. That’ll mean higher taxes and lower standards of living for workers. The Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (IFAC) estimates, if taxes weren’t to change, caring for the elderly would result in an annual deficit of between seven and 9.5 per cent of GNI* by 2050. To cover that, the government would need to take in 15-20 per cent more in tax.

The solution — as accepted last week by officials and politicians from the Department of Finance, the central bank and important NGOs — is to form a sovereign wealth fund. This fund is to generate a return in the coming decades which will help pay for hospitals and pensions in 2050.

It was a good event with lots of sensible public-spirited ideas. But I did wonder how else the problem might be solved.

People

The alternative to salting away money today, to partially defray the cost of an ageing society, is to bring in more young people so that we don’t have an ageing society.

There are two sources of young people: fertility (babies) or immigration. Ireland’s fertility numbers are high by European standards but trending down sharply. I suspect people are having fewer children because housing costs are so high but more on that point later.

The other source of young people is immigration. Immigration takes a couple of forms. A certain amount of immigration comes with EU membership — EU citizens have the right to live wherever they want.

Then there’s immigration on humanitarian grounds. Ukrainian refugees or asylum seekers are in this category.

Then there’s what I’ll term economic immigration. This amounts to issuing visas to immigrants that meet certain criteria. Ireland offers a small amount of these visas at the moment to certain high-skill workers.

Utmost Ireland

In the conference room last week, I wondered how many more visas, and of what type we’d need to issue to solve Ireland’s demographic problem.

The ratio of retired-to-worker is forecast to go from around 20 per cent today to around 45 per cent in 2050. To keep it at 35 per cent — about the level found today in most developed countries — Ireland would need one million additional prime-age workers by 2050. Over thirty years, that amounts to 33,000 additional workers per year. The following chart is from the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council.

If the purpose of the policy is to balance the government’s books (and keep living standards high), Ireland should target skilled immigrants. This is something the Canadians and Australians have done. They invite talent from top universities and in-demand professions.

For almost 20 years, Canada has aggressively courted high-skilled workers. It has a national skilled worker programme, a provincial skilled worker programme, and a new programme that offers visas to anyone who’s already qualified for the United States’ high-skilled worker programme.

Kapsalis (2020) looked at the effects of immigration on Canada’s public finances. They found that economic migrants paid about eight per cent more in taxes than they absorbed in public spending. The government’s net revenue from economic immigrants was more than three times greater than for native citizens. This is partially because of demographics: economic migrants tend to arrive in their peak taxpaying years. The following chart is from Kapsalis (2020).

There are two questions here. The first is when immigrants pay taxes. The second is how they impact the economy. On the first question, the evidence from Canada and the US shows that economic immigrants pay more taxes, sooner than humanitarian or other immigrants. The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration (2016) found that, in the US, it’s the second and subsequent generation of immigrants that are net taxpayers.

But that’s not to say immigrants of all types don’t benefit the economy. There’s a good deal of evidence to show that immigration makes national and local economies stronger. This is basically because each person is a little engine of demand. People spend money and create jobs in their vicinity. And there’s little evidence that immigration drives down wages.

Details

Of course, it’s not just a matter of issuing more visas. Adding one million workers over thirty years would necessitate a lot of investment. Starting with housing. About 15,000 extra homes per year would need to be built to accommodate them. Plus transport, hospitals, and everything else.

Where would they go? This is a surmountable problem. Ireland is among the least densely populated countries in Europe. On current trends, it’s expected to have 85 people per square kilometre by 2050. Adding an extra million workers would increase the density to 100 people per square kilometre. That compares to 434 people per square kilometre in England, 233 in Germany, 138 in Denmark and 117 in France. With the exception of arguably-overcrowded England, these are not overcrowded places. And Ireland – with only one real city – is not an overcrowded place.

The reality is that Ireland already needs to invest more ambitiously. Ireland has a big infrastructure deficit. Why not make this a national mission – to seek growth as an engine of higher living standards? Why not commit, over the next thirty years, to build infrastructure for seven million, rather than the current trajectory of six million? Our current posture — of being surprised and inconvenienced by growth — is the worst of all worlds.

Following this path would do more for the country than bring in taxpayers. A wholehearted investment programme would lower housing costs and generally make the country more liveable. I suspect, given better infrastructure, Irish families would choose more children.

The rate of population growth needed — 1.1 per cent per year — would be high but not outrageously so. That’s less than Canada’s population has grown on average each year for the last sixty years.

The advantage of setting a big ambitious target is that we can make big plans. Instead of building homes piecemeal, wherever we can squeeze them in, we could think seriously about what would be required to accommodate lots more people and give them high living standards. We could, for example, make rail investments so that our cities could get much bigger without adding to commutes.

What about emissions? In a reasonable world this would not be a problem, because the increase in Ireland’s population would be offset by a decrease in population elsewhere in the world. But that is not how national emissions targets are set. Ireland would need to make a case for clemency on the basis that higher emissions are not being driven by greater carbon intensity, but by more bodies. And one could see a scenario where faster population growth allowed Ireland to decrease carbon intensity, by justifying investments in rail and relatively low-emission urban living.

What about the sovereign wealth fund? It’s a good idea too. But it’s not without risk. Could our political system be trusted not to spend it? Could it be trusted to keep it at arm’s length, uncontaminated by political priorities? Would it be big enough to cover the costs of an ageing population?

If the sovereign wealth fund can clear all those hurdles it would help solve the problem. But it wouldn’t make our economy stronger and more vigorous. It wouldn’t lead to more people flourishing in Ireland.