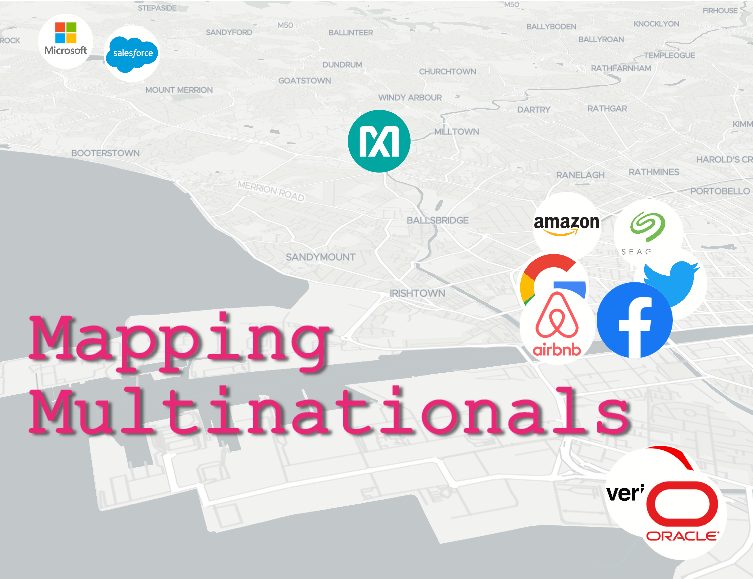

Since Christmas, I’ve gone through 330 corporate filings made by 261 individual companies, interviewed economists on both sides of the Atlantic and accessed hundreds of pages of archive documentation on global technology firms operating in Ireland. The result was the Mapping multinationals series of articles and map below.

- January 16: Unlocking Google’s €40bn Irish corporate empire

- January 23: Apple’s €180bn Irish (IP) licence to print money

- February 10: Trump’s tax law and tech’s €350bn dividend drive

- February 18: Inside Microsoft’s tangled Irish cash machine: $100bn dividends, a $53bn Singapore swoop, 21 firms & 6 countries

- February 27: From Menlo Park to Cayman – How Facebook’s Irish billions caught the eye of the US taxman

- March 12: From double Irish to green jersey: Why Silicon Valley is moving tens of billions in IP assets to Ireland

- March 12: Dell, IBM, HP, Analog and NCR – How hardware tech giants route their money through Ireland

- March 19: The story of how just 25 companies booked €100bn in profits in Ireland

My background is in international business journalism and I have covered big number stories through my career – from the first time French luxury goods giant LVMH’s profits topped €1 billion in 2005, to the vagaries of the Congolese copper and cobalt mine of Tenke Fungurume (one of the largest in the world), recently valued at $5 billion, and Kerry Group’s latest annual results pushing its market capitalisation over €20 billion.

Working on the financial flows directed through Ireland by tech multinationals, however, has forced me to find new ways of making sense of the figures I was looking at. They are truly staggering.

When reporting on the dividends paid by their Irish-registered subsidiaries to parents outside this country, I wrote that the €350 billion distributed since the start of 2018 was equivalent to one year of Ireland’s GDP and could fund the National Broadband Plan 116 times over.

There are more comparisons I could draw to get to grips with the striking figures I came across. The top 25 tech multinationals booked €100 billion in profits through Irish-registered holding companies in 2018. That’s 20 times as much as the entire nation spends on Christmas shopping.

As many jobs as financial services

The same 25 companies employed 43,000 people directly in Ireland. That’s about the same as the financial services industry, or the global workforce of Smurfit Kappa – and nothing to be sneezed at. These are quality, well-paid jobs.

The average gross salary of €87,000 – twice the industrial average wage – among those reporting payroll details means those 25 multinationals are injecting over €3.5 billion into their combined workforce annually. By my estimate, their share-based payments, benefits and employers’ PRSI are worth another €1.5 billion, bringing their payroll expenditure to €5 billion – a huge contribution to their employees’ lifestyle and to the wider economy.

Yet there is clearly a disconnect between the level of activity these multinationals actually conduct in Ireland and the financial flows they route through this country. One way of measuring this is to compare the level of profit they achieve at group level, as reported in consolidated accounts published in the US, and at Irish-registered subsidiaries.

Microsoft is an outlier in that it actually routed more profits through Ireland in 2018 than it reported in the entire world. While each of its 131,000 employees globally could be associated with an average pre-tax profit of $278,427 for the company, this ratio was $12.5 million for each of its 3,148 staff in Ireland.

Microsoft repatriates another $40 billion as it routes Asian business through Ireland

At the end of March, Microsoft’s Irish subsidiaries began publishing accounts for the year to the end of June 2019. They confirm the previously reported firmer anchoring of international financial flows in Ireland.

The group’s main trading company, Microsoft Ireland Operations Ltd, saw its revenue increase by $10 billion after it became the official licensor and manufacturer of Microsoft products to Asia following the absorption of a former Singapore subsidiary. “Operating profit and profit after tax increased by $556 million and $800 million respectively in line with growth in activities,” the company reported. It also increased staff numbers by nearly 400.

Its parent Microsoft Ireland Research, which charges royalties to other group companies such as Microsoft Ireland Operations for use of intellectual property and now covers Asia too, saw this revenue stream increase by more than $5 billion. Its pre-tax profit nearly doubled to $22.5 billion, largely as a result of a $17 billion gain on the absorption of a liquidated Dutch subsidiary. Its corporation tax charge, by contrast, dropped by $200 million as a result of a $1.4 billion “decrease from effect of expenses not deductible in determining taxable profit”.

Microsoft Round Island One, the Irish-registered, Bermuda-domiciled company previously used in the group’s double Irish tax structure, saw its revenue and profit plummet from $39 billion in 2018 to $10 billion in 2019 as the scheme winds down and substance requirements come into force in Bermuda.

Microsoft Ireland Research paid $37.5 billion in dividends in 2019, following $77 billion in 2018 as previously reported. It also declared a $13.6 billion dividend post balance sheet.

Microsoft Round Island One in turn reported receiving $33 billion from the intermediary holdings that then connected it to Microsoft Ireland Research. Combining this with other resources, it paid a $43.4 billion dividend to its own parents, continuing the massive repatriation trend observed since the US tax reform – albeit at a slower pace. It has declared an additional dividend of $24.6 billion since closing its accounts on June 30.

The $52.8 billion transaction transferring the assets of Microsoft Singapore Holdings to Ireland has not yet appeared on the balance sheet of the companies above. Corporate restructuring continued at pace after June 30, 2019, with subsidiaries involved in the transfer in Ireland, Luxembourg and Bermuda ultimately merged into Microsoft Ireland Research and Microsoft Ireland Round Island One in the second half of last year.

Other multinationals, while not as extreme, show a similar disproportion in the amount of profits booked by Irish-registered subsidiaries relative to the number of employees they have here.

The reason, of course, is tax. If business is not done in Ireland but declared here at the cost of multi-layered corporate structures, the fiscal advantage must far outweigh the expense involved in paying lawyers, accountants and auditors to run them.

I have detailed how these companies have been adapting to evolving tax legislation in the US, Ireland, and offshore jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands and Bermuda. From the infamous double Irish scheme, they have been flocking to the so-called green jersey, moving large amounts of intellectual property assets to Ireland in the process.

Associated revenues, profits and taxes have poured into this country, skewing national accounts in the so-called leprechaun economics episode. When Taoiseach Leo Varadkar gave the IDA’s inaugural special recognition award to Apple’s CEO Tim Cook in January, he welcomed the “€8 to 10 billion” in corporate tax receipts from multinational companies. By my estimate, his figures were out of date, as the 25 groups I analysed reported over €10 billion in combined tax charges in 2018. Some of this may be consolidated with subsidiaries in other countries, however, and Trinity Business School Associate Professor Jim Stewart warned me that these figures may differ from the actual cash payments made by companies to the Revenue.

The gap between the taxable financial flows and the volume of business actually conducted in a country is destined to narrow.

This advantage to Ireland, however, may be short-lived. If legislative changes coming into force in the Cayman Islands and Bermuda in the past year are anything to go by, the gap between the taxable financial flows and the volume of business actually conducted in a country is destined to narrow. New “substance” tests imposed by the two Caribbean jurisdictions under pressure from the EU and the OECD may well land on these shores if ongoing international negotiations on base erosion and profit shifting (Beps) come to an agreement.

Economists have shared their views with me on tax policy as it applies to multinationals at various points in this series, and this debate will continue. Regardless of the legislation applicable, the compliance tactics used by corporations and the resulting corporate structures, one key ingredient will need to be injected at increasing doses into this mix: transparency.

As a journalist, my work on this series was made possible by the Companies (Accounting) Act 2017, which forced most of the subsidiaries I analysed to publish accounts for the first time for 2018. It took Ireland four years to pass this legislation in application of an EU directive.

Yet some major tech companies remain shrouded in secrecy. Intel’s main Leixlip campus is operated by a branch of a company registered in the Cayman Islands, on which no data is available. Apple, IBM and Airbnb publish detailed accounts only for Irish holding companies consolidating many subsidiaries around the world, giving no visibility on their Irish operations.

This means thousands of employees and billions of euro in annual profits are located in structures that go unscrutinised in Ireland each year. By contrast, I as a journalist can join any employee, competitor or tax inspector in accessing the public filings of every domestic limited company in the country.

Levelling the transparency playing field

Some multinationals operating here are open and transparent – take Analog Devices’ detailed reporting of the assets forming part of a $20.7 billion intellectual property onshoring in 2018 accounts filed by its Irish subsidiary. Legislation on corporate reporting obligations could go a long way in levelling the playing field to ensure more do the same – and inform the debate on these companies’ role in the national economy.

In addition to well-reported data such as company ownership and dividends, more needs to be disclosed if we are to understand how multinationals transfer wealth across borders. Royalty payments, cost sharing for research and development and intercompany loans probably form the part of the iceberg still below the water line.

In the meantime, you might think companies specialising in circulating information would be quick to reply to journalists – think again. Among those whose documents filed in Ireland did not give me a full picture of their operations here, I got in touch with dedicated media contacts provided by Intel, Google, Airbnb, HP and Apple. Only Intel’s spokeswoman replied, providing information solely on the company’s number of employees in Ireland.

One last thing. As I drew diagrams of holding companies and subsidiaries stretching back and forth across the Atlantic to make sense of the corporate webs anchored in Ireland by these multinationals, I came across some seriously convoluted structures. None of them, however, approached the level of complexity I had encountered when completing the same exercise last year on the corporate empire built by John Magnier and his family around the Coolmore stud.