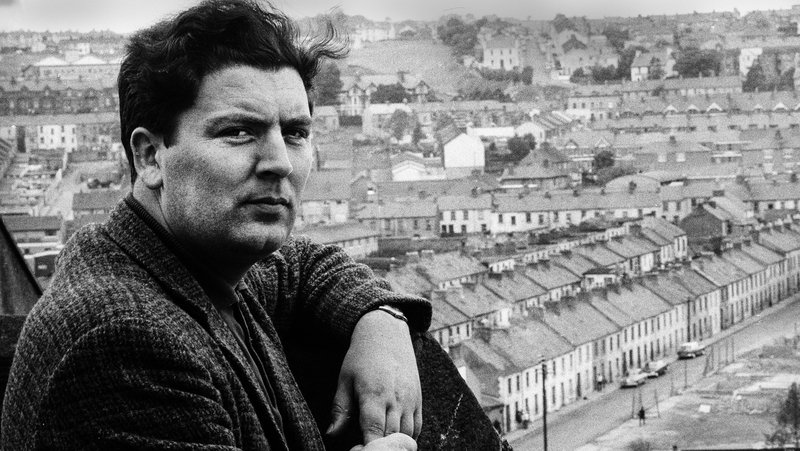

A bird’s eye view of where John Hume was born in 1937 goes a long way towards explaining his life. For if any place in the North had suffered the full political and economic consequences of partition, it was John Hume’s home city of Derry. It had a nationalist majority. It was cut off by the border from its natural hinterland of Donegal. It was also a treasured part of Unionist mythology as the ‘maiden city of the siege’. Was it any wonder that Derry became the cockpit of a North that exploded in 1969? And across the years, it seemed…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to read the full story?

Unlock this article – and everything else on The Currency – with an annual membership and receive a free Samsonite Upscape suitcase, retailing at €235, delivered to your door.