According to a recent report from the ESRI, Ireland’s population is expected to rise from 4.9 million today to six million by 2050.

It’s great news, to be sure. Sort of like surprise twins. But in order to accommodate 1.1 million new compatriots, we’re going to have to make some changes.

There are but three ways to accommodate a booming population. We can build outwards, build upwards, or not build at all. I’ll call them the Houston model, the Tokyo model and the San Francisco model.

Ireland has to pick one.

Don’t build

San Francisco’s economy is like Dublin’s on steroids. Where Dublin is home to the European outposts of some US tech companies, the San Francisco Bay Area is the capital of global tech.

Like Dublin, the Bay Area is sprawling and low-density. Most of the city of San Francisco is made up of two story terraced houses with gardens. Silicon Valley is full of small, tidy, detached bungalows.

Planning in San Francisco is a cousin of our own. The rules are open to interpretation, and local objectors have a lot of power to block new developments. So it’s very hard to get anything built.

This has resulted in a mismatch between supply and demand. There are more well-paid technology workers arriving in the city than there are houses for them. The rich tech workers take the houses. So ordinary people, without six-figure salaries, get turfed out. Housing costs in San Francisco are now the highest in the world.

This is the path San Francisco has chosen. Locals don’t want greater density near their houses. And they want the historic character of their neighbourhoods preserved.

The upshot is that, superficially at least, San Francisco has kept its 19th century charm. But the city is unaffordable to all but the richest. Residential rent is the highest in the world at €47 per square metre. Rent in Dublin, by comparison, is €18 per square metre.

San Francisco shows what happens when a city doesn’t change. When an in-demand city doesn’t build new houses, the price system does the work of allocating housing. And what the price system does is allocate houses to the richest citizens.

San Francisco shows it’s not possible for attractive cities to remain unchanged. If the built environment doesn’t adapt to the new people, the new people will displace the old ones. Things may look the same. But the character of the city will change regardless.

Build out

San Francisco is like the control group. It shows what happens if you do nothing.

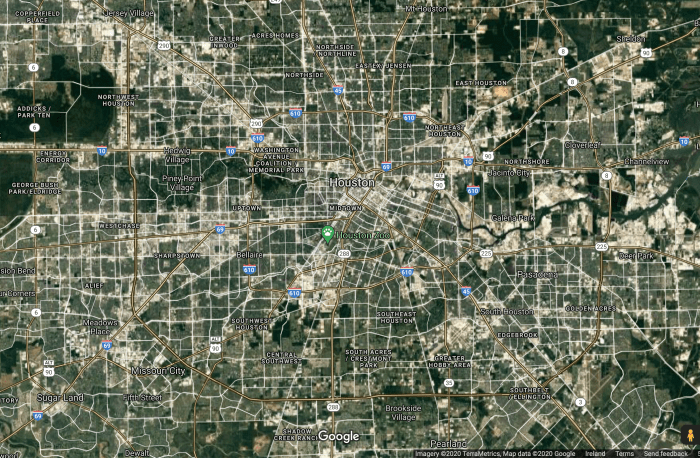

Houston, Texas is the next one. Houston’s story is similar to the San Francisco Bay Area — booming oil industry economy, lots of people want to move there. Both cities now have a population of about seven million people.

The difference is that in Texas, planning rules are lax. You can build wherever. So Houston has grown along with its population.

In the last thirty years, Houston’s population has grown by 89 per cent. It added 3.3 million new residents. (In the same period San Francisco’s population grew 23 per cent.)

Lax planning rules have allowed supply for new housing in Houston to keep up with demand. Despite its size and wealth – it’s the capital of the US oil industry – it’s an affordable place to live. Rent in Houston comes to €10.78 per square metre, compared to San Francisco’s €47.

Houston is nobody’s idea of paradise. But Houston (and other US sunbelt cities like Atlanta, Austin, Nashville, Phoenix, San Antonio, Las Vegas or Dallas) show that rich, growing cities don’t need to be unaffordable.

You could say Houston took the easy way out, by sprawling further and further into the exurbs. The result is a city that’s cheap but hard to get around, charmless and car-clogged at ground level.

Dublin at its worst is a mixture of San Francisco and Houston. Local objectors make it difficult to increase density within the M50; so, to relieve the pressure, the city sprawls into Kildare and Meath. The same goes for Ireland’s other towns and cities, which have been growing through sprawl.

An interesting thing about Houston is that, in recent times, its sprawl has slowed. Instead of building housing estates on empty land at the edge of town, developers are “infilling” empty and underdeveloped lots within the city. The city has naturally gotten denser. Even though it’s cheaper to build at the edge of town, developers are infilling because there’s a limit to how long people are willing to commute.

This gets at something important. The binding constraint on the size of a city isn’t mountains or coastlines. It’s commuting time.

Build up

A city that relies on cars and motorways turns into a mess above a certain size. Even Galway, a city of about 100,000, has serious traffic problems.

Rail is the solution. Commuter rail systems, like the DART, have the capacity to transport huge numbers around a city. Much more than any motorway.

And the beauty of a commuter rail network is not just that trains are nice (which they are). It’s that they can make a city much more affordable. By building more densely along a rail network, you can increase supply and therefore push rents and house prices down. You don’t need to cover half of Leinster in concrete. And you spare people having to make long daily commutes by car.

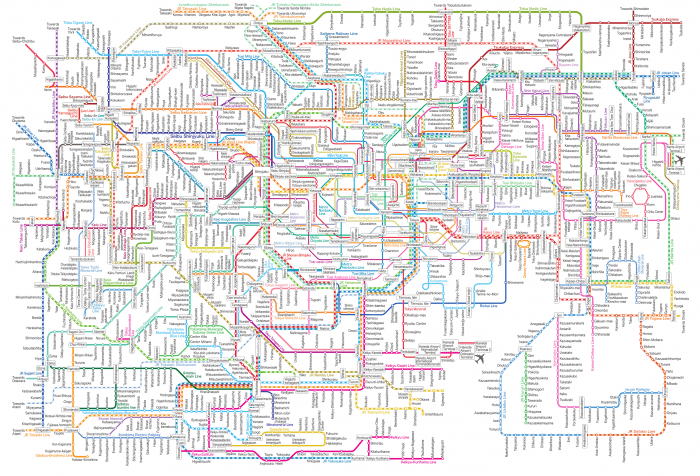

This is how Tokyo came to be the miraculous place it is. Tokyo is the world’s biggest city and the world’s richest city, and it’s affordable. It has a population of nearly 38 million people — more than five times that of Houston and the Bay Area.

Rents in Tokyo are €22 per square metre. This is more than Dublin, but half the rent in San Francisco and far less than its peers, global megacities like New York, Paris or London. Rents there have barely risen in ten years. And what’s more, the city has a greater share of one-bedroom apartments than other cities, which overstates its true cost on a metre squared basis.

The city runs on rail. Randomly clicking around on Google Maps, anywhere in the city seems to be most two hours by public transit from anywhere else. In other words, in the time it takes to get from Balinteer to Finglas by public transport, Tokyoites can traverse a city of 38 million people.

The Japanese understand that housing and transport are two sides of the same coin. Indeed, much of the city of Tokyo was built by private railway companies. They built new rail lines into the countryside and developed the land around the stations, building everything from department stores to universities. The neighbourhoods are now known as rail integrated communities, says John Calimente in a paper in the Journal of Transport and Land Use:

“Rail integrated communities are defined as high density, safe, mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly developments around railway stations that act as community hubs, served by frequent, all-day, rail rapid transit that is access primarily on foot, by bicycle or public transit.”

Even the throbbing district of Shibuya — whose iconic crossroads is now a symbol of downtown Tokyo — was developed by the Tokyu Corporation rail company in 1934, to drive traffic to its railway lines.

There are other examples of rail-centred development closer to home. Northern Europe is full of liveable, affordable cities built on their rail networks. But Tokyo has the combination of an efficient rail network and Houston-style liberal planning laws. This has resulted in a steady stream of new housing supply, complemented by accessible rail transport. Japan consistently built almost 1 million new homes each year over the last decade; the US built 1.25 million, though its population is 160 per cent bigger. So Tokyo has the best of both worlds: Munich or Amsterdam’s efficient rail-based transit system, and Houston’s permissiveness to new development.

Development and opposition in Ireland

Opposition to development takes many forms in Ireland. Some mistakenly think privately built homes don’t help affordability, others have a fixed idea of how development should look, others just don’t want anything built near them. But we need 28,000-49,000 houses every year for thirty years. So opponents of specific developments might reflect on whether their aesthetic or philosophical preferences are compatible with building enormous numbers of houses, year-in year-out.

Ireland has a passable commuter rail network. But it should be much better. We should go ahead with the DART underground – a tunnel connecting Heuston and Connolly. This connecting tunnel (known in Germany as an S-Bahn) would dramatically increase the capacity, efficiency and reach of the overall network.

Having upgraded the trains, we should upgrade the homes near them. We should zone for greatly increased density near rail stations. That goes for fancy neighbourhoods along the DART as well as quieter spots on the Maynooth line. We could take a leaf out of the Tokyu Corporation’s book and make new rail-centric neighbourhoods that are liveable and walkable, while we’re at it. We don’t want to be Los Angeles – a city that spent more $10 billion on its subway network, but didn’t zone for higher density near stations. So the $10 billion subway system is mostly empty.

And finally, Transport and Housing should be combined in one ministerial portfolio. You can’t solve for one without the other. It’s perhaps too big a leap to ask the government to farm out housing development to railway companies. But at least the Department could start thinking about these matters in a joined-up way.