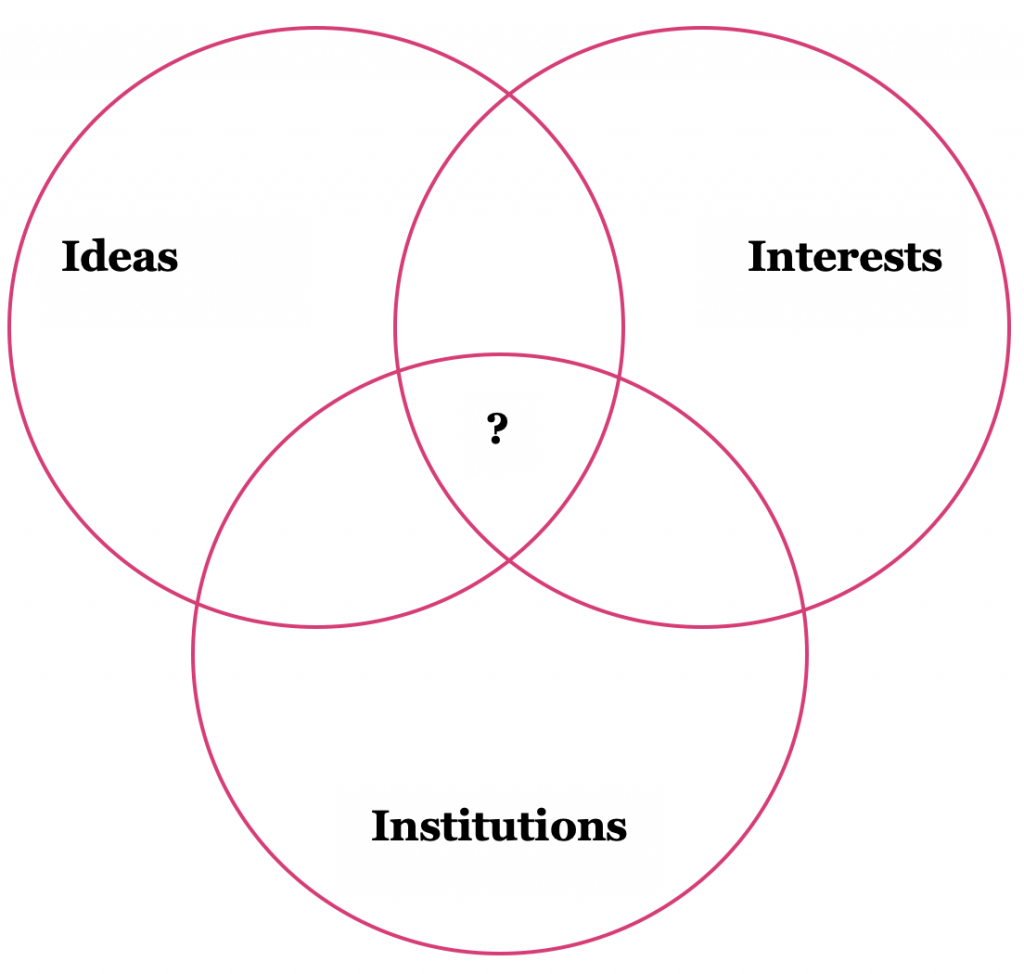

We are ruled by the interaction of ideas, interests, and institutions.

Ideas are mental models providing a coherent set of beliefs about cause-and-effect relationships. Ideas often lead to ideologies—guiding sets of beliefs. For example, if I have an idea that the government can spend when the economy turns down, and save when the economy turns up, I’m probably a Keynesian in my beliefs. If I have an ideal that the only way the economy can evolve is via the liquidation of unproductive sectors of the economy, I’m probably a Libertarian in my beliefs.

Interests are the goals or policy objectives that the central actors in the political system and in the economy follow. The interests of the governing class, for example, or the asset-owning class, may be quite different from the interests of those without assets. Similarly, as I argued last week, the interests of the young and the old may be very different, and these are not unrelated to the inability of the young to acquire assets like housing and pensions.

Institutions, and here I mean political institutions, both national and international, establish the rules governing the processes everyone else follows. Those institutions can be extractive, or they can be inclusive, to use the terminology of Acemoglu and Robinson in their books Why Nations Fail, and The Narrow Corridor. Extractive institutions are controlled by small groups to remove resources from the rest of the population. Inclusive institutions bring larger groups into the governance process, and so it is commensurately harder for the smaller would-be extractive groups to exploit those powerful institutions for their own ends.

We need to talk about where we are going

In part 3 of this series asking where are we going as a nation, I want to look at the institutional design of our society, analyse our ruling ideas, and ask which sets of interests will continue to dominate. Last week, in part two of the series, I argued that where we are go as a country depends on our choice of the structural features of our economy, on the dynamic path we choose to walk. That dynamic path will determine the hopes and expectations of our citizens in the context of the changing, as I argued in the first part of the series.

The diagram above puts a question mark at its centre, because where ideas, interests, and institutions go, so Ireland goes. At any given moment, one of these features dominates our discourse. I’ll give you four examples of their interaction. You can generate many more, and you might disagree with my characterisations, but you’ll get the gist of the framework.

The dominant institutions were the new political parties that had won the war of independence. The dominant interests were those of the nascent state and the Catholic church against the landed class.

Take the period right after the formation of the state, from say 1918 to 1924. The dominant idea was republicanism and separation from our former masters. The dominant institutions were the new political parties that had won the war of independence. The dominant interests were those of the nascent state and the Catholic church against the landed class.

Take another example, the movement from a relatively closed, autarkic society to an open one, in the late 1950s and early 1960. The dominant idea was openness to trade, to ideas, to export-led growth. The dominant institutions were the Catholic church and the government, and the dominant interests were Ireland’s new manufacturing and service-based merchant classes, winning authority over the agricultural power bases of the past.

Take another example, the period of austerity from 2008 to 2013. The dominant idea was cutting the states’ spending and increasing taxes to win the support of the international bond market. You can think of that idea as either fiscal consolidation or austerity. The dominant institutions were the ECB, IMF, and the European Commission. The dominant interests were those of the state.

Take yet another example, the period we are in today. Employment has reached more than 2.3 million people for the first time in our history as a state. Our unemployment rate is 4.9% on a seasonal basis, and falling. The Irish economy is growing very strongly, recent tax data supporting the notion that our economy is at, or near, the top of its economic cycle. Despite the good economic news, the dominant idea is fundamentally negative: Protecting the gains of the last few years from the threat of Brexit generates a least-worst set of policies at best (no pun intended). The dominant institutions are the Departments of Finance and Foreign Affairs. The dominant interests are of those with assets of all kinds, including housing and financial assets. Whether these interests will continue to dominate is another matter, entirely.

When the flow of ideas are poisoned by nationalism, when interests of one group dominate all others, when institutions fail to mediate between different interest groups and privilege one group above all, the nation itself may fail. How might Ireland avoid this fate?

Ruling ideas?

An ideology is a set of guiding beliefs. We often think about people or groups as following one dominant ideology. I think this view is mistaken. The first thing we should understand is that ideologies are not anywhere near as important as we think. In fact, I think we may well be capable of multiple ideologies, depending on the context. I would conjecture the average Irish citizen is maximally libertarian around their own home, wanting to be mostly left alone save for their property rights being respected. They are socialist at the community level, wanting an average level of engagement for everyone. At the national level the average Irish citizen is somewhere between centre-left and centre-right, depending on the issue in question, with social issues in particular skewing left/liberal for people under about 50. If there are multiple, context-dependent ideologies, then it matters that they can be in conflict with one another quite often.

The question becomes how we resolve the tension between these ideologies within ourselves. I find it striking to see the same people decrying the homelessness problem in Dublin and championing objections to the only policy remedy that would alleviate this problem — an increase in housing supply

Let’s think about housing, as an example. Take the NIMBY or BANANA (build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone) crowd who very quietly dominate our polity, and whose interests our political system responds to. At the national/centrist level, they would like there to be more housing. At the community/socialist level, they would like homelessness and insecure tenancies to end. So far, so lined up. But at the individual/libertarian level, they recognise their interests (as measured by the negative impact of a large increase in local housing on the value of their major asset) are not aligned with the other ideological levels I’ve described. As that household-level concern dominates, so the other ideologies are left behind, the objections are put in, and off we go.

The question becomes how we resolve the tension between these ideologies within ourselves. I find it striking to see the same people decrying the homelessness problem in Dublin and championing objections to the only policy remedy that would alleviate this problem — an increase in housing supply. I often wonder how the tectonic plates of ideology roll on top of or around each other, and to be honest, I don’t have a good sense of exactly how this works, except that I think there’s a convenient fall guy (fall-person?) one can always blame: the government.

Where does the government gets its ideas and ideologies from? Ideologies are not ideas, of course. Ideologies are more operative, more usable than ideas. They tell you want to do in a given moment, like a kind of social operating system. Copenhagen Business School’s Cornel Ban’s recent book Ruling Ideas gives a wonderful overview of how ideas become entrenched, and dominant, because they are held by the technocratic class, who learn those ideas in prestigious schools as generalisable laws derived from past date that they can apply to their own countries.

They find Ireland is fairly poor at stakeholder engagement in developing regulations, and dreadful at figuring out whether new regulations actually work via a process called ex post evaluation.

This is why technocratic rule is a mistake. Technocrats run on certain types of data from the past, threaded through frameworks from the past. They often forecast from the past to the future, and feel free to pronounce upon the future. (As someone who once wrote a book called Ireland in 2050, I can attest to this fact). Technocrats are hardly ever exposed to the present. Only democratically-elected leaders are forced to come face to face with the people they serve, and deal in the present on the present’s terms. This is why democracy is so important.

Our institutions are precious.

Every few years the World Governance Indicator report spews out a bunch of reports on the quality of our institutions. The figure below reproduces the values of the past few years. The WGI includes a measure of confidence in their findings, and also ranks Ireland in terms of other countries. Unsurprisingly, we do well as a country, consistently ranking in the 90th percentile and above on many measures. That said, there has been a deterioration in our scores for many measures. Mouse over the various measures to see each in turn. Elements like regulatory quality have fallen from 1.91 in 2008 to 1.6 in 2018. Government effectiveness was 1.5 in 2008, it is 1.42 in 2018. Quantitative measures are not the be-all and end-all of the universe, but if every measure is going in the wrong direction, you might have a problem of institutional deterioration. The OECD monitor the development of Ireland’s regulatory environment, and find similar results using a different measure in their unputdownable page-turner, the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook. They find Ireland is fairly poor at stakeholder engagement in developing regulations, and dreadful at figuring out whether new regulations actually work via a process called ex post evaluation.

That said, while our institutions may have deteriorated somewhat over the last decade, when people are asked about their experience of the public services they generally give good or very good marks. The chart shows a the percentage of respondents who express confidence in various elements of the public service last year, for both Ireland and the OECD. The national government does well, with 62 per cent of respondents voicing satisfaction, relative to 45 per cent for the OECD. The judicial and educational systems come across very well too, at 68 per cent and 83 per cent respectively. The health system, unsurprisingly fares worse than the OECD average, but still attains a 64 per cent score.

Ideas, interests, institutions: What does it all mean?

The ruling idea of our time is presented as a question in two parts, and each citizen may draw his or her own meaning from their own answer to each question. The first question is: what form of economy and society will best protect our citizens in a post-Brexit world? The second is: what form of political settlement will best knit the island together over the coming 50 years, both North and South? The answer to the first question entails thinking about how open we are, how our economy and society is structured institutionally, and what kinds of elements might replace those that aren’t working well for us. The second answer is about peace and security. Without a good answer to the ‘national question’ most people can get behind, we risk sliding back towards a grim past the last generation thought it had freed us from.

Democracy is how we take ourselves forward as a nation. Our democracy is being challenged at the moment, because of a change in our ideas about ourselves—our identity. In the next part of this series, I’m going to ask: Who are we now?

The ruling ideas of most times in history are not economic, or political, really, but fundamentally are about dignity. In an economy, most things have prices, because most things can be valued. (As we saw last week, assigning value is a little difficult for the public sector, but even there, there is hope). Without blowing your mind all together, dear reader, let me bring in philosopher Emmanuel Kant, who contrasted things that have prices with things that have a dignity. In his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, page 33, Kant wrote:

“In the realm of ends everything has either a price or an intrinsic value. Anything with a price can be replaced by something else as its equivalent, whereas anything that is above all price and therefore admits of no equivalent has intrinsic value.”

The intrinsic value Kant was talking about was dignity. The ruling idea of our time has to, somehow, find a way to express the dignity of the nation in a way that most people can agree with. The answer to those two questions—on a form for our society, and on a form for peace-have to include a way for us to talk about dignity. What is homelessness, but a drastic diminution of a family’s dignity? What is the health crisis, if not a loss of basic dignity for the sickest?

I think a conversation based around those question will find our ruling idea for the 21st Century. I think the groups in whose interests our society functions would participate in such a conversation, and with sufficient support, we might see some of the means by which their powers are deployed reduced. Our institutions clearly need to be strengthened, but there is hope. The hope comes from who we are, now, and not just where we have been. The hope comes from our democracy. Democracy is how we take ourselves forward as a nation. Our democracy is being challenged at the moment, because of a change in our ideas about ourselves—our identity. In the next part of this series, I’m going to ask: Who are we now?