In my previous life as an agricultural reporter, I remember the excitement caused by a proposal five years ago to convert the ESB’s coal- and oil-fired Moneypoint power plant to burn biomass. It quickly emerged that the idea had been floated by an anti-wind energy lobby group in conjunction with an oil and gas company and would involve 8 per cent of Ireland’s farmland to grow energy crops if it was to avoid imports. Thankfully, it didn’t catch on.

For years, what to do with the Co Clare plant has been the question that crystallised the evident need to move away from fossil fuels, while paralysing policymakers faced with dismantling the most tangible mark of scant State investment on the west coast.

On the one hand, year after year of greenhouse gas inventories published by the EPA have shown that every time Moneypoint is switched off for maintenance, Ireland’s carbon dioxide emissions fall significantly. This is before the pollution and other impacts of sourcing coal as far away as Colombia are even examined.

On the other hand, the plant has continued to play an important role in the Irish electricity system. Coal is cheap, and burning it when weather conditions are calm or demand peaks has helped offset fluctuations in wind power supply. This role, however, has increasingly been taken up by more modern gas-fired stations. Moneypoint has lost out to them in multiple recent capacity auctions whereby generators pledge such short-notice power availability to the national grid.

Two years ago, the ESB halved Moneypoint’s 200-strong workforce in the face of dwindling demand for its services. The company has committed to ending coal use by 2025. Regardless of political pressure, the remaining jobs were under increasing threat. The Co Clare coastal behemoth’s days looked numbered – until Friday.

The ESB’s multi-billion-euro “Green Atlantic” plan to convert the site into a renewable energy centre, complete an offshore wind farm and hydrogen fuel production into the 2030s, is not only the most exciting single project unveiled in this sector to date. The announcement is also a sign of hope for the west coast as an industrial investment destination.

Location, location, location

While the ESB’s peat-fired power stations in the Midlands became anchors of Ireland’s own rust belt after closing down in December in the wake of ill though-out plans for conversion to biomass similar to the one once mooted for Moneypoint, the western plant was saved by one thing: its location.

Offshore wind generation is the next source of power for Ireland. Its technologies have been proven in northern Europe and developers are now actively working to deploy them along the east coast, where shallow waters make the installation of traditional ground-mounted turbines easier.

Just last Monday, Madrid-based Ocean Winds announced that it had applied for a licence to investigate a site off the Co Wicklow coast. The company is a joint venture between Portugal’s EDP and France’s Engie, two of the few remaining large European energy utilities that had yet to pile into the Irish wind energy market.

With the development of floating wind farms, however, Ireland’s deeper waters are becoming the new eldorado. One such project, the Emerald wind farm, is already under development by Shell and Simply Blue off the Cork coast. This is where Moneypoint’s location becomes a strong point.

The coal-fired station is situated near the country’s other historic generation asset at Ardnacrusha, 60km upstream on the River Shannon. Together, they have shaped the national grid.

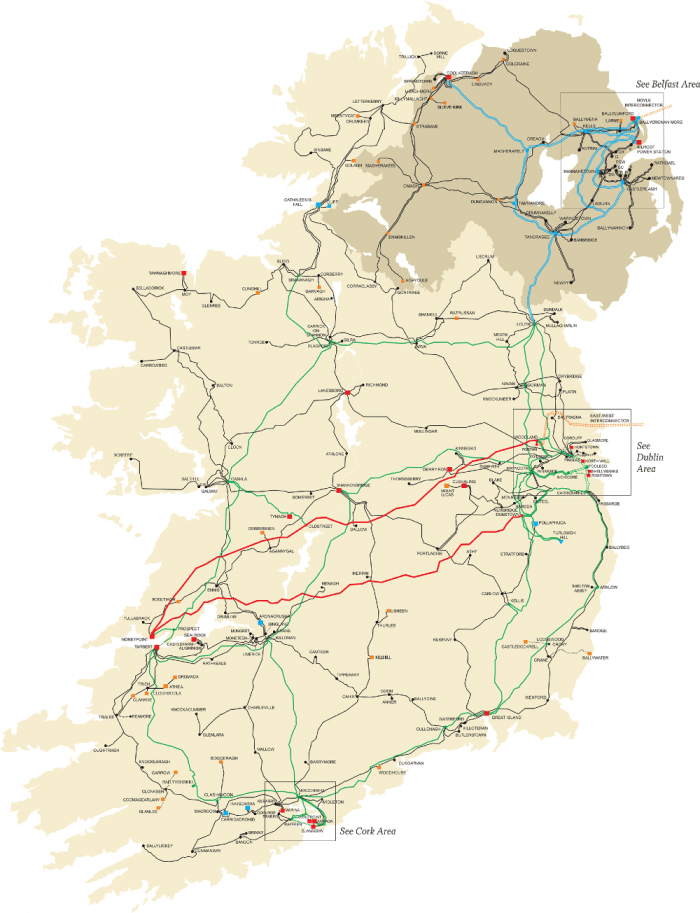

A quick look at the system’s map shows that the two lines connecting Moneypoint to the greater Dublin area are the only extra-high voltage pieces of infrastructure on the network. Their capacity makes the Shannon estuary an ideal place to land power for distribution across the country. Grid connections have been one of the major bottlenecks for the roll-out of renewable power in Ireland and existing infrastructure is an invaluable asset near any project.

The current coal-fired station itself delivers up to 915MW. the ESB is now planning a 50-50 joint venture with Norway’s Equinor to develop a 1,000 to 1,500MW floating offshore wind farm 16km off the Clare coast – 400MW by 2028, and a second phase in the next decade. This initially leaves plenty of space for other developers to plug into the existing grid connection once the coal-fired plant shuts down by 2025.

The latest government target is to have 5,000MW of offshore wind generation capacity installed by 2030.

The strength of the grid infrastructure connecting the site also means that it will be possible to route electricity from offshore wind farms off the Clare and Kerry coasts to export interconnectors – whether the existing ones to Britain, or the proposed Celtic Interconnector to France. Operator Eirgrid announced in recent days that it had identified a final route to land the undersea cable at a beach in Youghal, on the border between Co Cork and Co Waterford, and connect it to the wider grid. The next step is planning permission.

Increasing the share of wind and solar power in the national energy mix is not without technical challenges. The quantity and quality of renewable electricity fluctuate constantlydepending on the weather. To address this, the ESB’s initial development at Moneypoint, due to break ground next month, is a €50 million synchronous compensator – a giant vacuum tube containing a massive flywheel spun by excess electricity when available, capable of being reversed into supplying a steady supply of current to stabilise the grid at short notice whenever required. The State-owned company claims the compensator will be the largest of its kind in the world.

The next development at the site, in parallel with the construction of the planned offshore wind farm in about five years’ time, is an industrial hub for the construction of concrete bases for the turbines and their assembly. Limerick’s neighbouring Foynes port is included in the project. When asked by The Currency about the ESB’s precise role in this, generation and trading head of strategy Padraig O hIceadha said the group had no plans to engage in turbine manufacturing itself, but would provide the infrastructure for other companies to locate there. “It will be to the west coast’s wind what Aberdeen is to North sea oil,” he added.

The final part of the ESB’s plan for Moneypoint – though not until the next decade – is a plant to convert excess renewable energy into hydrogen. The gas can then be used as heavy transport fuel in lorries, buses, trains and ships, or to generate more electricity for peak demand period – a capability also included in the plan.

The ESB estimates that the conversion of Moneypoint to offshore wind will avoid 1.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions per year by 2030. This is one fifth of all greenhouse gases released by electricity generation nationwide in 2019.

On paper, the plan displays more actionable joined-up thinking on energy decarbonisation than any Irish State body has shown before. Its implementation could turn Co Clare into one of Europe’s main renewable energy centres.

Communities hit by the end of peat extraction in the Midlands, where the Government has been scrambling to cobble together bog restoration and home insulation projects only after hundreds of jobs were lost, must be looking on with envy.