The Cobblestone pub in Smithfield is special because it feels a bit like stepping back in time. Or, at least, into a pub in West Clare. It’s a bit run down. On an evening, you might find three sessions going on in different corners of the place. The atmosphere is perfect.

The Cobblestone is on a corner at the top of Smithfield market in Dublin. The buildings and land on either side of it are derelict. The pub occupies the ground floor of a three story building.

Across the road from it on Smithfield Market is a wall of apartment buildings, between seven and fourteen stories in height. They were built in the 1990s. If Smithfield were to be developed today, and if planning wasn’t an issue, those apartments might be forty stories tall.

That’s because Dublin is getting richer. The technology industry has come to town. The wealth it generates is literally seeping into the ground: land prices have rocketed since the 1990s.

Now there’s a plan to demolish the derelict buildings around The Cobblestone and replace them with a nine-story hotel. The Cobblestone would lose its smoking area and one of its live music spaces. And its front bar would be adjoined to the hotel as a residents bar. The atmosphere would be ruined.

So there’s a conflict. The Cobblestone is one of the places that makes Dublin unique. But it’s sitting on a plot of very expensive land.

You might say that it’s not a difficult conflict at all — just save The Cobblestone. Simple as.

But The Cobblestone is an awkward example of a very important and wide-ranging problem in our country. It’s an example of hard cases making bad law.

The problem

The other day on Twitter I put it like this: “Ireland has very high land prices and very low density. This is an unnatural state of affairs. Expensive land wants to be developed densely. Indeed, this is why towns and cities exist.”

Land has gotten more expensive in Dublin, and Ireland, for basically positive reasons. It has a thriving economy, good quality of life, is culturally interesting. For these reasons, it’s attractive. People from the rest of Ireland and the rest of the world are moving to Dublin. Tourists want to check it out.

The problem is when we don’t build new infrastructure to accommodate all these new arrivals. If we don’t build new places for them, what happens is they come in and displace the existing Dubs. And you get the situation we’re in now.

And if you don’t want to see lots of construction, and taller buildings, the only other way to lower housing costs is to make the city less attractive – perhaps by cancelling rubbish collection or sacking the teachers, or by kicking out TikTok, or closing hotels. That would also work. It would obviously be nuts. But if you want the cost of living to fall, these are basically the two options. Either expand supply to satisfy the existing demand, or contract demand so that it matches the existing supply.

Special case

The Cobblestone is an interesting case for two reasons. One is that it’s not being adjoined by any old building, it’s being adjoined by a hotel.

Hotels are now the enemy in Dublin. The housing shortage has gotten to a point where tourism – our largest indigenous industry – is considered a bad thing. Or at least, the hotels tourism necessitates are. Hotels are seen to be taking space away from housing. So, for The Cobblestone to be replaced by a hotel of all things is especially galling.

We’re in this through the looking glass world where anything that attracts people to the city, or makes it better, can be seen as bad because it exacerbates the housing crisis. 5,000 new jobs at Tiktok? Airports opening back up? Successful policy initiative to remove cars from the city centre? Universities climbing the global rankings? All bad news for Dublin.

The other interesting thing about the Cobblestone case is this idea of conservation. The Cobblestone is a special case because it’s so beloved. The petition to protect it got 20,000 signatures in a few days. But the desire to conserve our existing built environment saturates our planning regime.

What would happen if a developer tried to build a nine story apartment block at the end of your road? It’s likely the local WhatsApp would be up in arms, and the neighbours would probably be successful in stopping it. They’d likely argue a nine story building would ruin the character of the neighbourhood.

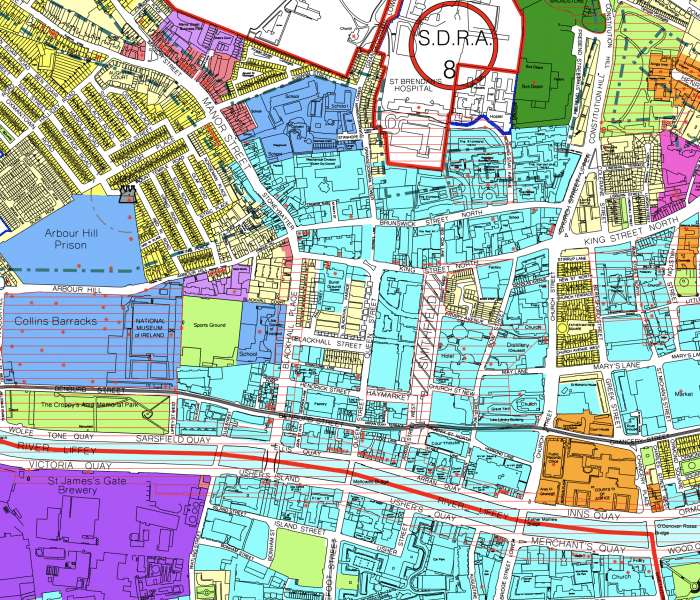

This idea of conservation is at the heart of our dysfunctional housing market. We don’t want our neighbourhoods to change. So we elect councillors who draw up development plans that forbid drastic change. The reason your local WhatsApp group probably isn’t battling with plans for a nine story apartment blocks is because those blocks have already been made illegal almost everywhere in Ireland. Your local representatives have ensured it.

Ronan Lyons reckons the government’s target of 29,000 homes per year is way short. He thinks we need closer to 50,000 homes per year for the next twenty to meet the demands of our growing population. The fact of the matter is that there’s zero chance of us hitting that target under our existing planning regime, with an effective prohibition on high density city living and a veto for locals. To get 50,000 houses per year we need new construction everywhere. It doesn’t need to be nine stories tall, but it needs to be in every neighbourhood in the city of Dublin and all over the country. It’s something we’re never going to do if we hold onto this impulse to conserve things the way they are. Our cities need to change quite radically. But that doesn’t have to be something to fear.

The Lexus effect

The other point is that right now, when we’re not building enough, it always feels like we’re fighting a rearguard action. The new developments are bland hotels or office blocks. The ones getting replaced are beloved cultural spaces.

But this is what you get when there’s not enough construction. When the amount of construction is rationed by the planning system, as it is now, new construction focuses on the top end of the market.

This makes sense: the fewer units of a product that get made, the more high end it’ll be. The first cars were toys for rich people. Then, mass production made them a product for anyone.

As the writer Matthew Yglesias has pointed out, in the 1980s, the US government restricted the number of cars Japanese carmakers could export to the US (this they did because US carmakers were angry about losing market share). In response to the quotas, the Japanese carmakers decided to move upmarket. They developed the Lexus and Infiniti brands. They moved upmarket because, only being allowed to sell a small number of units, they had to maximise the margin they made on them.

So when the planning system restricts development, it does two things: it changes the quantity of units (bad for affordability in itself) and it changes the quality of the units that get built, making them more upmarket.

We know how to create great cultural spaces. Indeed, they appeared all over Ireland during the recession. All that needs to happen is for rents to be low. With low rents, cultural spaces emerge naturally.

So the good news is that we don’t have to fight a rearguard action! We can actually get ahead of the change, and have plenty of cool cultural spaces alongside hotels and apartments and houses. The new parts of our cities don’t have to be bland.

Japan is my urban planning nirvana. Japan is a place that’s ruthlessly free of nostalgia. The Japanese build much more stuff of all kinds than we do. (They do this because their planning system is much more permissive, but that’s a story for another day.) Anyway, when you walk around Tokyo or Osaka, the place is buzzing with culture. Even though the buildings are all new, they’re full of weird, small, quirky businesses and public spaces. There are little sheebeen pubs all over the place, with enough room to hold eight old men leaning against a counter in the centre of the room. They don’t have that corporate blandness you get in new parts of western cities. Japan isn’t bland because it has relatively cheap rents, and it has cheap rents because Japanese people build way more than we do.

You don’t have to go all the way to Japan to see cities with low rents and thriving cultural scenes. Manchester or Glasgow or Berlin or Pittsburgh all fit the bill. But those cities’ glory days are behind them. That’s why they’re cheap. What makes Tokyo or Osaka notable is that they’re cheap and they’re growing. That’s the trick Ireland needs to pull off.

So we can have our cake and eat it, in the sense that we can welcome people to the country and have vibrant evolving cultural spaces that are uniquely Irish and have affordable housing. New cultural spaces can be just as good as the old one we’re clinging onto. The places that embody Irish culture don’t have to be frozen in place from 1950 or whenever.

But we can’t have our cake and eat it in the sense that we can’t have affordable housing and conserve our existing neighbourhoods. Either we embrace change, and allow our neighborhoods to radically change in line with their growing population. Or we spend the next few decades fighting about rents, and visitors, and highly-paid technology jobs.