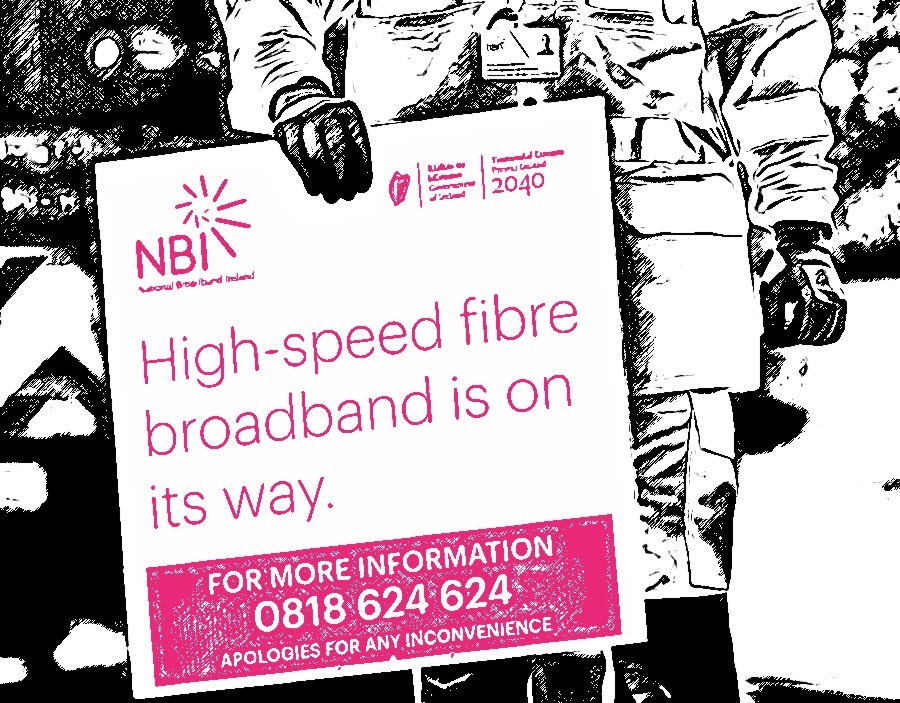

I have to declare an interest. I live at the end of a country lane in a house connected by an old copper phone line that risks falling apart at any point. In fact, it already has – twice. Since remote working became the norm, I have learned how to perfect the position of my mobile phone in the window to allow hotspotting every time the landline gives up. In other words, I depend on the delivery of rural broadband to earn a living into the future. I have a vested interest in the National Broadband Plan being a success,…

Cancel at any time. Are you already a member? Log in here.

Want to read the full story?

Unlock this article – and everything else on The Currency – with an annual membership and receive a free Samsonite Upscape suitcase, retailing at €235, delivered to your door.