As I wrote last week, we’re in a new regime. The economy has finally run out of slack. You can see it in everything from airport queues to used car prices and staff shortages.

And it can be seen in rising interest rates.

Interest rates are the starting point for all investment. Everything else is priced in reference to them.

That’s because the real interest rate is the return that’s on offer by doing nothing. Interest rates are the opportunity cost of going out and putting your money at risk.

You might think the question “what happens to stocks when interest rates rise” would be fairly straightforward.

But it turns out to be tricky to answer. It’s tricky in the first place because it hasn’t happened much in the last forty years. So we don’t have a whole lot of experience to draw on.

It’s also tricky because the effect of rising interest rates is ambiguous and subtle and depends on two important things.

The first thing is the reason rates are going up. The second thing is the type of company in question.

Why are rates rising?

There are two reasons rates might be expected to go up: either because the economy is growing, or because inflation is going up. Both scenarios push up rates, but both have opposing effects on stock prices.

As we’ve seen, higher rates mean the opportunity cost of making an investment is higher. In this way, higher rates mechanically lower the value of all assets, including stocks.

On the other hand, higher rates are associated with greater spending in the economy. More spending tends to be good for stocks.

So there’s a push and pull going on. Higher rates make stocks less valuable by increasing the opportunity cost of investing. But they’re also associated with faster spending, which is good for them.

For rising rates to be good for stocks, the benefits of greater spending in the economy need to be greater than the drawback of a higher opportunity cost.

In other words, rates need to be rising because of higher growth, rather than higher inflation. Inflation isn’t great for stocks because, even though it does increase spending and companies’ revenue, it’s usually bad for profits. It’s bad for profits because companies’ costs usually go up by as much as the increase in revenue.

There’s only been one serious bout of inflation in the rich world in the last century. It occurred in the 1970s. And in the US, the 1970s was the second-worst decade for investors since the 1930s.

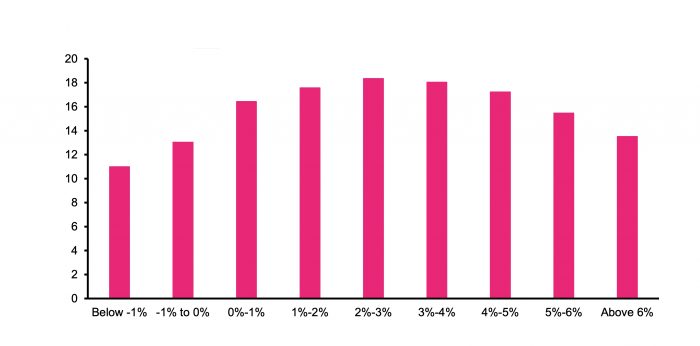

There’s a goldilocks level of interest rates where stocks do best. They’re the interest rates associated with low inflation and stable growth. The following chart from Michael Mauboussin shows how stocks have varied over time at different interest rates. Higher valuations are good — they mean investors are feeling optimistic about stocks. Valuations are at their lowest when interest rates are very low (not enough growth), and very high (too much inflation).

What type of company is it?

I said the effect of interest rate changes depends on two things — the reason for the change, and the type of company.

As we’ve seen, most companies do badly during times of inflation. Their revenues go up but their costs go up too. And the opportunity cost of investing in them goes up. Taken together, it’s usually bad for stock prices.

But it’s not true of all companies. Some companies are able to pass higher costs along to their customers. These lucky companies can protect their margins, and might even benefit from the higher spending.

So that’s a factor that affects how a stock will handle rising interest rates and inflation — their pricing power.

A second one is one I’ve mentioned in this email a couple of times. Writing about the markets in 2022, it comes up a lot. It’s the issue of duration — or the length of time an investor needs to wait to get their money.

Remember that interest rates are the opportunity cost of waiting around for an investment to pay off. But not all investments pay off in the same schedule. Imagine a company that owns a rusty old oil rig in the North Sea. That company’s value doesn’t derive from its profits in the distant future. It derives from the here and now.

By contrast, imagine Flutter’s American betting business, FanDuel. Flutter is losing money in the US because it’s investing hundreds of millions in marketing to acquire customers. The hope is that in future, all these customers will be loyal FanDuel punters, and Flutter investors will get big dividends.

The difference between the rusty oil rig and FanDuel is time. Investors in FanDuel need more patience than investors in the rig. And that’s where interest rates come into it. High interest rates are a tax on patience. They make waiting around for future earnings less attractive.

So in a world of rising rates and inflation, you want to own a company that can pass prices hikes along to consumers and that doesn’t need to reinvest much. It’s a tough ask. Which is why stocks — like bonds and everything else — are having a bad 2022.