The winter energy situation is starting to come into focus, and it’s very bad.

Since the beginning of August, the gas price has shot upward. The following chart shows UK gas futures price curves. Each curve is the market’s best guess at gas prices at future dates. The date of the market’s guess is shown. As you can see, futures prices across the curve have risen and risen in the last year.

When you plug those wholesale prices into the formulas that estimate household energy prices, you get mad numbers. Citi, a bank, has forecast UK household energy bills could rise to £5,800 (€6,800) per year by April of 2023.

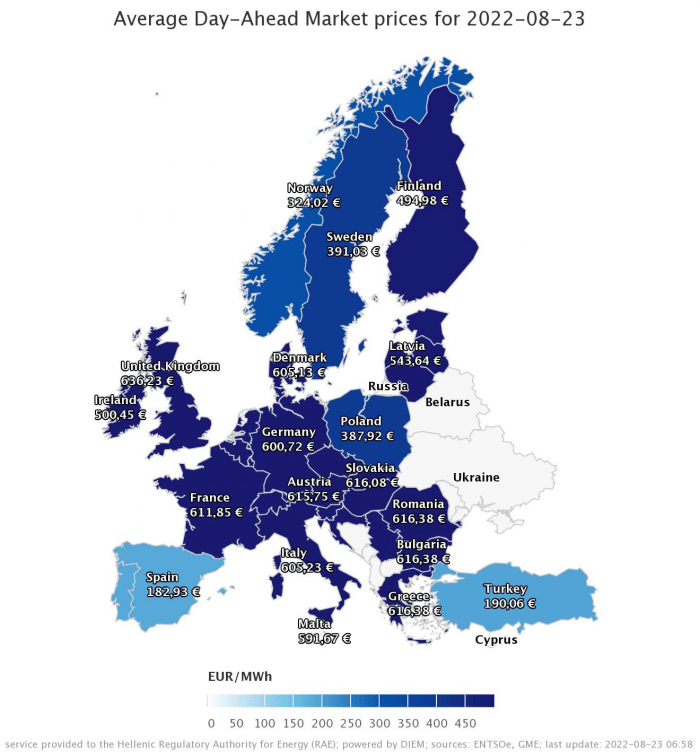

It’s a similar story across Europe. On Monday alone, TTF Natural Gas futures rose 19 per cent, German Baseload rose 18.5 per cent, and French Base Power Forwards rose 19.8 per cent. The following map from Javier Blas shows day-ahead electricity prices across Europe; €75-100 per MWh would previously have been considered expensive.

Yesterday FinGrid, the grid operator in Finland, said: ”Finns should be prepared for possible power outages caused by electricity shortages this coming winter”. And yesterday Alexander De Croo, Belgium’s Prime Minister, said Europe is facing “five to ten” difficult winters.

If Ireland came anywhere close to Citi’s €6,400 estimate for 2023 UK household energy bills would utterly ruin many households and businesses.

But that number is so preposterously large that it won’t be allowed to happen. It would put half the country in poverty.

Studying the deadly Bengal Famine of 1943, the economist Amartya Sen observed that deadly famines are more likely in authoritarian than democratic societies. That’s because, in democracies, vote-seeking politicians ensure that relief gets to people in need. Authoritarian rules don’t care or don’t know about ordinary people. This was later called Sen’s Law.

What we’re going to see this winter in Europe is Sen’s Law in action: governments will be forced to bail out households. And the bills will be huge.

Demand destruction

Even given bailouts, energy prices for households will be astronomical. That’s because the energy crisis is one of quantities as well as prices. There isn’t enough gas to go around. We need to use less of it. No amount of bailouts will resolve this.

Prices need to stay high to force everyone to cut back. Households will have to use less heating, less petrol and less electricity. The same for industry and commerce.

The problem with the demand destruction strategy is that Ireland isn’t an industrial powerhouse. There aren’t twenty giant factories guzzling up a big chunk of our nation’s gas supply. Only 19 per cent of Ireland’s energy went to industry in 2020. By contrast, 61 per cent of Ireland’s energy was used for residential and transport purposes.

Industry has already cut back by, for example, shifting production overseas. On a European level, industrial energy demand is below where it was at the bottom of lockdown in 2020. It’s down about 20 per cent.

What about data centres? According to Eirgrid, in 2020, demand from data centres was forecast to reach about 70 kilotons of oil equivalent (ktoe). In 2020, according to SEAI, Ireland’s total energy demand came to 11,258 ktoe. So data centres currently make up about 0.6 per cent of annual energy usage. To be sure, annual energy usage includes everything from jet fuel to gas-fired central heating, electricity and diesel-powered cars. If you focus instead on electricity demand, data centres use up about a quarter of the total.

The upshot is that there’s no way households can escape what’s coming. The question is how much energy usage they can cut back, and how much relief governments will offer.

Cagey companies

When demand for face masks mushroomed in early 2020, the private sector did its thing and within a couple of months there were enough masks to go around.

But this time around, don’t expect private enterprise to perform miracles. The energy industry has been here before. High prices signal to energy companies that it would be profitable to frack more gas and drill more coal; everybody fracks and drills and digs at the same time; and the price collapses, leaving energy company investors holding the tab.

That’s what happened in the first fracking boom, beginning in the mid-2000s. Billions were invested in the new technology. But fracking was a victim of its own success: the market got swamped, and more than 200 North American producers went under after 2015. Collectively, they owed more than $130 billion.

Now, the gas industry mantra is capital efficiency. Producers are very slow to invest in new production before shareholders get their piece.

It’s a similar story with coal. The commodity trading giant Glencore is the world’s biggest coal producer. As pointed out on the Odd Lots podcast, Glencore has been taking heat from investors for years now over coal’s nasty emissions profile. But all of a sudden, on its most recent earnings call, a Bank of America analyst asked what it would take to delay its ramp down of coal mining, and invest to increase production in the short term, “to give the world the energy it needs”.

The risk for Glencore is that it pumps up coal production, and then coal finds itself out of fashion once again.

Desperate governments

If energy companies are being cagey with their investment, governments are pulling out all the stops. The plan is to ship in as much north American fracked gas on liquified natural gas (LNG) tankers as possible.

European countries are investing in floating storage regasification units, or FSRUs. These giant machines are basically floating liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals. They take the gas from LNG tankers and pump it into the national system. The German state government in Lower Saxony is reported to be facilitating the first of these terminals at eight times the normal speed.

Germany has acquired two FSRUs this summer, which will contribute 13 per cent of the country’s natural gas demand this winter. Another two projects are planned to come on stream next year. Italy, the UK, Greece and Lithuania have also made deals to secure FSRUs this year.

In Ireland, plans for an LNG terminal in North Kerry are moving along slowly. A decision is expected by September 9th. In the event of a yes, it would be years before the gas came on stream. In the meantime, we should brace ourselves for broken household budgets and protests on the streets.