When I joined the exciting world of investment punditry in 2011, everyone seemed to be a value investor.

Value investing was the thinking man’s investment strategy. It was the strategy of Warren Buffett, Sir John Templeton and Seth Klarman.

And even better, value investing is intuitive. It says you should buy cheap things, and then wait for the market to price them properly. It feels right.

Value investors don’t bother with flashy companies. They rummage in the bargain bins. They look for unfashionable businesses that, seemingly, don’t have much to offer.

As well as being intuitive, value investing has pedigree. It was one of the first factors (a characteristic shared among securities, one with a different risk and return profile to the wider market) to be discovered.

Value stocks, aka cheap stocks, were found to outperform the rest of the market by quite a lot. From 1926 to 2015, value stocks in the US returned 12 per cent per year, versus 7 per cent for the overall market. Compound those numbers and you end up with a huge difference: €10,000 invested for 30 years at 7 per cent yields €76,000; at 12 per cent it yields €300,000. The value factor has been found in markets all over the world, and it’s been found as far back as we have reliable data.

The only problem is, even though value returned an average of 12 per cent per year in the US, it didn’t return 12 per cent year-in and year-out. It waxed and waned. There were years-long periods when it disappeared altogether.

Unfortunately for the value investors of 2011, they were in for a tough time. When the market rebounded after the financial crash in 2009, the value factor was nowhere to be seen.

After 2009, value investors who stuck to tried and tested principles – by buying boring, cheap utility companies and the like – got left behind. The following decade was all about flashy growth stocks. Companies that looked to have lots of profits in their future did best.

Growth is the opposite of value. Where value is all about the here and now: how cheaply can I acquire today’s profits? Growth investing is all about the future: what’s the most amount of future profit I can acquire today?

From my desk at MoneyWeek, and later at investing newsletters, I watched the value investors sticking stubbornly to their strategy, despite all available evidence. Speaking in 2019, Warren Buffett’s investing partner Charlie Munger said:

“… like a bunch of cod fishermen after all the cod’s been overfished. They don’t catch a lot of cod, but they keep on fishing in the same waters. That’s what’s happened to all these value investors. Maybe they should move to where the fish are.”

Over the following years, natural attrition weeded out most of the value investors. And I know for a fact that people stopped subscribing to value investing newsletters. By 2021, nobody was talking about value anymore.

The comeback

I started this newsletter in 2020. Not to toot my own horn, but in January of 2021 I suggested the timing looked good for a value. I said:

“A consequence of the bull market is that value is now trading at an all-time discount to growth. Value has never been better value. If the spread of value to growth from the chart above reverts back to its normal range, value will outperform.

“… If you’re not excited by the prospect of five per cent returns over the medium term, and are of a contrarian and patient bent, then a value strategy might be for you. Talk to your broker about it.”

About two months after I wrote that piece, the value factor started to stir.

The way academics measure value is high minus low (HML). HML is the returns on the cheapest stocks minus the returns on the most expensive stocks, with cheapness defined as the ratio of book value to market cap.

Anyway, on March 2021, the HML factor perked up. Between March 2021 and the rebound after the financial crisis in April 2009, HML had returned an average of 0.0 per cent per month. That March, it returned 5.0 per cent. And in the 15 months since then it has returned an average of 2.1 per cent, each month.

Are the value investors finally vindicated? Not quite. HML is long cheap stocks and short expensive ones. What happened starting in 2021 isn't so much that cheap stocks did great, but that expensive stocks did terribly.

Having spent the last two years or so of the 2009-2021 bull market buying any old crap (Gamestop, crypto, and so on), in March the market finally got a clue. It started dumping the dumbest, lowest-quality companies.

According to Dan Rasmussen, the "go long cheap stocks" side of HML barely broke even in the first half of this year, returning only 3 per cent. Being short expensive stocks, on the other hand, returned 23 per cent.

What we're seeing here is a regime shift. They happen every decade or two in financial markets. A theme that has worked for years stops working, and gets replaced by another one.

The theme going back to 2009 was for low interest rates, and high returns to growth. Those two points are not unrelated. Interest rates are the opportunity cost of future returns. Low interest rates make returns from the distant future more appealing in the present. When interest rates are low, you might as well buy Tesla in the hope of making a killing in 2029.

Now interest rates are rising and people are thinking about profits in the here and now. And the collective spell is broken. People are less bored and gullible and excitable. They've been burned recently. They know valuations don't rise indefinitely.

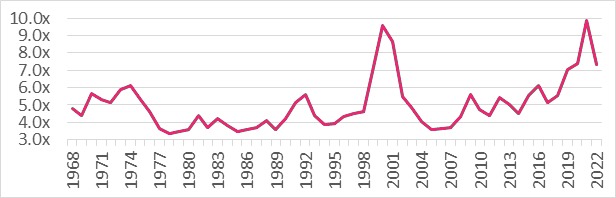

How much more has value to go? It could be a fair bit yet. The following chart comes from Kenneth French. It shows the valuation of the most expensive stocks relative to the cheapest ones.

As you can see, cheap stocks have made up some ground on expensive ones. But they're a long way off their long term average. There's more to this story.