Talking to ESRI energy economist Niall Farrell about energy markets last week, I was struck how, behind the scenes, people work very hard on complicated problems so that we can all have the basics of modern life.

Electricity markets, he told me, are complex. They used to be crude and simple: there was a semi-state electricity provider. It got paid a fixed percentage – in addition to its costs – for the electricity provided.

The big problem with this model was that it gives the semi-state no incentive to be efficient. It has an incentive to be less efficient, since it’s paid a percentage over its costs. These cost-plus contracts have been shown to lead to higher prices for consumers.

There are other problems with cost-plus: it doesn’t take demand into account, so the supplier isn’t incentivised to produce more when more is needed.

So the energy economists came up with a better system, the one we use today. They opened up the market to investment and competition.

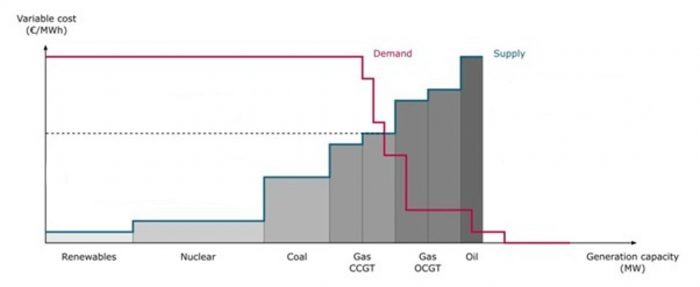

The market today is designed around a standard supply and demand model, where the price and quantity of electricity produced is determined by the point where the electricity demand curve meets the electricity supply curve.

The demand curve shows how much electricity is demanded by consumers at each price level. The supply curve shows how much producers are willing to make at each price level. As prices go up, producers will be willing to produce more, and consumers will be willing to consume less.

The electricity market supply and demand diagram looks like the basic econ 101 one, except the “curves” consist of a series of jagged right angles.

The jagged steps up the supply curve represent different sources of power — wind, hydro, coal, gas, solar etc — which each have their own unique cost structures. Wind producers are happy to produce a certain quantity at a certain price, gas producers another, and so on.

The jagged steps in the demand curve represent different sources of demand. Higher prices might convince a household to use less electricity, but have less of an effect on a hospital.

Gas is extra-significant in our electricity mix because it tends to be the marginal supplier of power. Especially in times of high demand. That’s because certain gas plants have the quality of being “nimble”, as Niall Farrell put it: “I like to think of it like a rugby team. You have the solid fellas, they’re grinding it out. And they’re constantly running. There are certain old gas systems that run the whole time. They’re the base load. Then you have really nimble fellas that come on when you need them to do a quick burst.”

The way the economists designed this market is interesting. The suppliers get asked for the lowest price at which they’re willing to supply electricity. The offers get ranked from cheapest to most expensive. The price gets set by the marginal power source — where the supply and demand curves cross over — and every supplier whose bid is lower than that marginal price gets the marginal price.

So all the other sources of power down the supply curve — the slow gas plants, the wind, hydro and solar — they all get the price set by gas, even though they would be willing to supply electricity more cheaply.

Why design the market this way? The big advantage is that prices convey information. The information embedded in the price is what coordinates everybody in the market. In the short run, it tells people to put on a jumper or power up a gas turbine.

The sum of investments

In the long run, the price tells people how to invest. In the long run, the investments are what make or break the market. When, as you’re seeing now, wind generators are making far more than their marginal costs, investors pump money into building more wind turbines. When household bills shoot up, people invest in Kingspan and solar panels.

The old cost-plus system didn’t work efficiently because there wasn’t a proper price signal and therefore there was no investment. Since we implemented a marketplace for electricity, there’s been huge investment in renewables and in their complement, natural gas (which as I wrote last week has the quality of being easy to ramp up and down — a good quality when renewables are intermittent).

To be sure, the elegant design of our electricity markets will be of little comfort to anyone this winter. The market price bills will be unaffordable. What should we do?

One option is to scrap the whole electricity marketplace and go back to a cost-plus setup. That would succeed at lowering energy prices. But it would leave us with a not-cheap energy sector that’s incapable of changing and not up to the task of decarbonisation. Not a good idea I would have thought.

Another option is a windfall tax. The idea here is to grab some of the money made by, for example, wind generators, whose marginal cost of supplying electricity is way below the marginal price on offer, and use it to bail out consumers.

There are some problems with windfall taxes, though. Electricity markets are complex. It’s not clear exactly how much windfall profit suppliers are making. For example, some of them hedge their long-term profits with financial instruments, so they don’t necessarily see all the upside. “There may be clever ways that I haven’t thought of [to levy a windfall tax], but every way I can think of will lead to a potential unintended consequence,” said Farrell.

The other problem is that windfall taxes tell anyone thinking of investing in a new wind farm or gas turbine that a) the return on investment will be lower and b) the rules of the game are subject to change arbitrarily.

A price cap is another approach. Under a price cap, the government sets a limit on the amount suppliers can charge customers for electricity. The problem with this approach is that during times of high demand — say, seven o’clock on a Wednesday in December — the marginal electricity suppliers aren’t paid enough to supply the market. That might mean electricity shortages for customers, and it might mean less investment in extra supply.

The Spanish decided to cap the wholesale price of gas (with the taxpayer covering the difference between the market price and the gap). As a result, Spain now uses twice as much gas for power generation as previously, imports more gas from Russia, and has spent a fortune on gas subsidies.

Any intervention in the market will make it less efficient. That’s unavoidable. The trick is to minimise the long-term damage to the market’s functioning while giving the people relief.

Bram Claeys, a senior advisor with the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP), has come up with a clever scheme that threads the needle. The easiest way to describe it is graphically:

So normally, gas costs B. But because of Russia, gas now costs D. Under the normal marginal pricing rules, consumers would pay the top of D, the red dotted line. But under Claeys’ scheme, instead of the price being set by the top offer, it would be set by the second-highest offer. That would determine what everyone else gets — wind, solar, oil etc. Then in addition, the gas suppliers would get their offer price. So the total cost paid by consumers would be A plus B plus D — but not C.

This is a neat compromise solution. It reduces electricity prices in a simple enforceable way. It compensates gas producers fairly. And it doesn’t jettison the signal we need to guide investors and households — the price.