The collapse in returns available from fixed income assets is a major challenge, and the coronavirus shock has driven them even lower. While regulatory and other reasons have kept many investors glued to their traditional exposure, this is a growing problem for Pension Funds, Insurance Companies and others with a long-term horizon. Meanwhile, the attraction of positive, growing and sustainable equity income is compelling. In response, an historic shift by long-term investors from Fixed Income to Equity Income is increasingly likely.

Banks: the canary in the mine

Bank shareholders are having a tough time. Squeezed margins and weighty regulation have dampened profit and potential for traditional banks around the globe. For many banks, the absolute and relative decline in their share prices has followed inexorably. In contrast to generally buoyant stock-markets, the index of European bank shares, for example, recently touched a 30-year low.

Some argue that bank shares are now ‘cheap’ and represent an attractive buying opportunity. In many cases trading below the balance sheet valuation of their equity, they argue that even a modest improvement in business performance would spark a rebound in bank share prices. They may well be right. But the bigger issue for investors is not whether bank shares might enjoy a bounce sometime soon, but whether their long-term de-rating is signalling something more fundamental:

Is the de-rating of bank shares the canary in the mine signalling interest rates are tethered near historic lows?

Interest rates & bond yields: lower for longer & longer

Theoretically, there are at least two reasons for interest rates to be positive. Firstly, the need to compensate creditors for postponing consumption i.e. the time value of money, and secondly, the need to compensate creditors for the varied but unavoidable risk of not being repaid i.e. credit risk.

In practice, since at least the earliest references to debt in the ancient world, the fact of debtors compensating creditors has been widely accepted. This continued through the classical period, and even in Medieval Europe where usury was forbidden by the Christian Church, interest-bearing loans were the norm.

But in the wake of the Lehman collapse in September 2008, the global economy and banking system faced meltdown. Many feared a re-run of the great depression. This view failed to reckon with the powerful tools available to policymakers which have since been used with an aggression unprecedented in peacetime. Around the globe today, the inversion of centuries of history – with many creditors now compensating debtors – starkly defies both theory and historic practice.

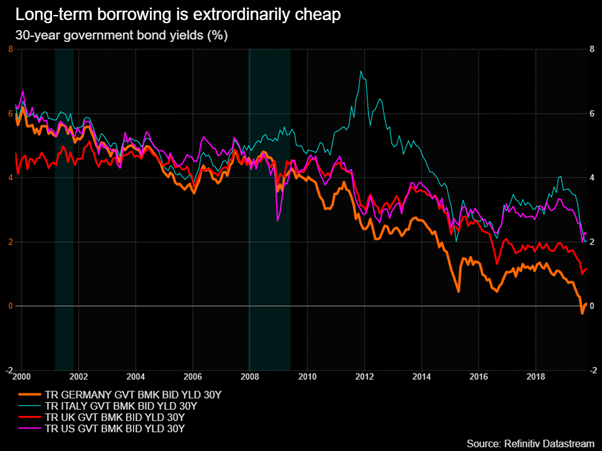

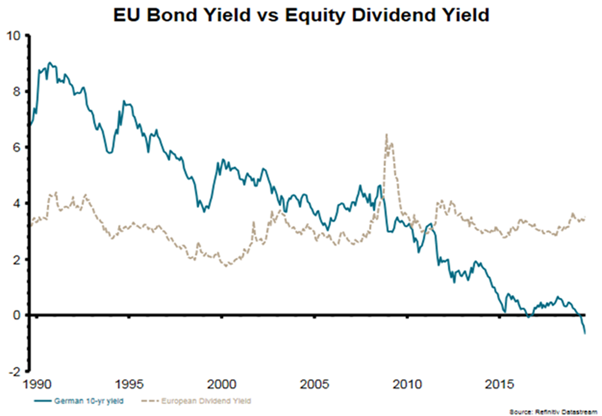

For example, negative nominal official interest rates have become the new normal in Europe and bond investors at every maturity out to 30 years are now all but paying for the privilege of loaning money to the German and Dutch governments. Remarkably, mortgage borrowers in neighbouring Denmark are also being paid to borrow and buy houses. More generally, long-term borrowing is extraordinarily cheap with negative real rates embedded globally.

The past few months have been particularly instructive. The continuing attempt by the Federal Reserve to shrink its historically expanded balance sheet was forced into a sharp reversal. While the intricacies of the repo market have generated much comment, the key message for long-term investors is:

Bloated official balance sheets and low interest rates/bond yields are the new normal.

*****

A Dramatic Re-Expansion of the Federal Reserve Balance Sheet (by $400bn – to over $4.1 Trillion)

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

The past few months have been particularly instructive. The continuing attempt by the Federal Reserve to shrink its historically expanded balance sheet was forced into a sharp reversal. While the intricacies of the repo market have generated much comment, the key message for long-term investors is that:

Bloated official balance sheets and low interest rates/bond yields are the new normal.

Long-term investors: the challenge of falling fixed income returns

For long-term investors, this is creating a difficult double challenge: the rising cost of meeting liabilities combined with the falling return on fixed income assets.

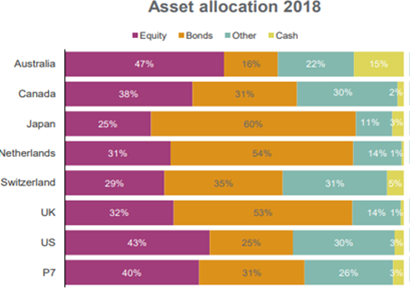

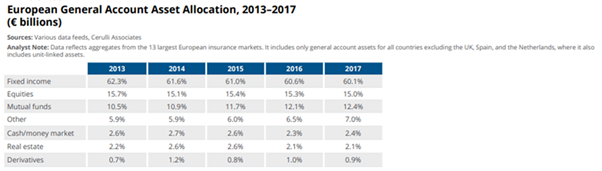

This is especially acute for Pension Funds and Insurance Companies who traditionally have a very high exposure to fixed income assets for ‘risk’, regulatory and ‘liability matching’ purposes.

According to data from Willis Towers Watson, global pension fund assets totalled over $40 trillion at the end of 2018. The ongoing exposure to negligibly returning cash and fixed income assets is a growing challenge for these funds.

Source: Willis Towers Watson

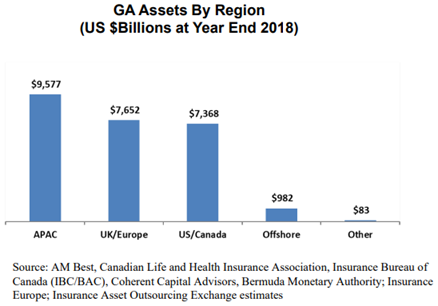

Meanwhile, ‘general account’ (GA) insurance assets are estimated at $25.7 trillion globally as at the end of 2018.

Once again, the exposure to negligibly returning cash and fixed income assets is a clear and growing challenge. The allocation to such shrinking returns in Europe is striking.

The price to earnings ratio is a relationship normally cited for equities. But as a tool for comparing the earnings of any asset, with the price of that asset, it can be usefully employed elsewhere. It is after all just the earnings yield inverted.

So, for example, a yield of 1% is a price to earnings ratio of 100 i.e. a ratio roughly that of the Japanese and Nasdaq stock-markets at their peaks in 1989 and 2000 respectively. Described this way, the large and continuing exposure of long-term pension and insurance investors to fixed income is troubling. The argument that it reduces ‘risk’ seems especially misplaced.

In a 2006 memo simply called ‘Risk’, Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital sought to broaden the debate about investment risk from the actuarial and the conventional. In an updated memo in 2018, ‘Risk Revisited’, he returned to the fray with the crucial insight that:

‘Investors face two major risks: the risk of losing money and the risk of missing opportunities. Either can be eliminated but not both. And leaning too far in order to avoid one can set you up to be victimized by the other.’

For pension scheme members, trustees, actuaries and regulators, it’s time to stop sleepwalking mechanically into such an outcome. The author and economist, John Kay, has summarised the issue with a typically apt analogy:

‘Do not confuse security with certainty. The man who knows he will be hanged tomorrow has certainty, but not security. His fate is not much more comfortable than that of the saver who today plans to use bonds as a vehicle for retirement saving — the certainty such a saver will achieve is the certainty of a low standard of living in old age.’

The Shift to Equity Income: the new paradigm

Over the long-term, a share price is a function of the cash earnings distributed to shareholders. Simply put, as equity investors we should always remember that we are owners of a share in a business and that the value of the business to us is ultimately determined by the cash that we take out of it.

Assuming a business is broadly happy with its capital structure, when it makes a profit it has two options for deploying it:

1) Re-invest it – in either the existing business, or by acquiring all or part of a new one.

2) Distribute it to shareholders – in either a dividend, or by buying back and cancelling some outstanding shares.

Ideally, as shareholders we want the management of the business to take the first option up to the point where it generates a positive net present value to us, and to take the second option with the residual.

But in the real world even the most appropriately motivated and incentivised management will find it impossible to live up to this ideal. There are just too many variables outside their control. The best that we can reasonably hope for is a sensible combination of the two.

From the businesses in which we own shares therefore, we should demand capable management to generally generate profit, re-invest or acquire profitably for the future, and/or remunerate us via a dividend and/or share count reduction.

Fortunately, a large diversity of businesses are dividend payers and many of these are enjoying profit growth in excess of the opportunities to re-invest profitably.

Crucially, stock-markets have been travelling a very different path to fixed income markets. Although rising strongly since the global financial crisis, stock markets have continued to offer earnings and dividend yields comfortably as attractive as the historical norm.

In contrast to their bond brethren, stock investors have continued to be compensated by attractive income flows in return for risking their capital. Furthermore, earnings and dividends offer the crucial capacity to grow. This has wrenched open a yawning gap between the positive and growing income on offer from many stocks, and the static and negative income on offer from many bonds.

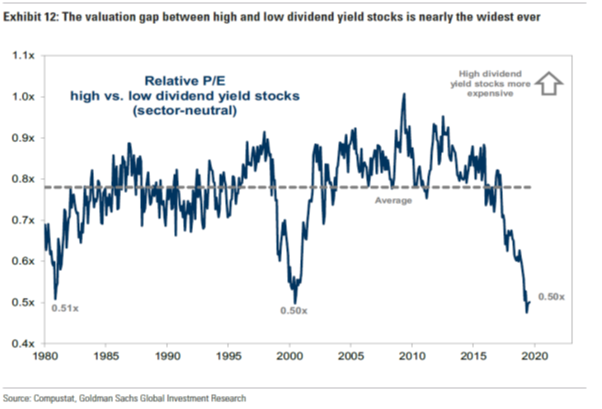

Interestingly, within the stock-market itself there has been a dramatic shunning of relatively higher-yielding stocks. On an industry neutral basis, higher-yielding stocks are now on offer at historically cheap prices relative to their lower-yielding counterparts.

Only twice over the past four decades have higher-yielding stocks been so out of favour:

- At the peak of global bond yields in 1982 when, for example, the US 30-year treasury could be bought at a yield of almost 14%.

- At the peak of the technology bubble in the Spring of 2000.

On both occasions, the attraction of relatively higher-yielding stocks was swamped by extreme alternatives which proved temporary. The catalyst for a repeat is widely debated but impossible to know for sure.

But there is no doubt that the collapse in returns available from fixed income assets is a major challenge. While regulatory and other reasons have kept them stubbornly glued to their traditional exposure, this is a growing problem for Pension Funds, Insurance Companies and other long-term investors. Meanwhile, the attraction of positive, growing and sustainable equity income is compelling. In response, an historic shift by long-term investors from Fixed Income to Equity Income is increasingly likely.