In my column last week, I argued Ireland needed to diversify its industrial base. I wrote the piece after Budget 2023, when Paschal Donohoe fretted about our reliance on multinational money – much of which does not derive from these companies’ Irish operations.

I am actually returning to the topic on the site today, where I try to assess the likelihood corporation taxes will fall next year.

Back to the budget. Paschal Donohoe had some really interesting comments about various types of investment funds – including those heavily involved in the property industry – that largely got overlooked.

Near the end of his speech, Donohoe said he was kicking off a review of the Reit and Iref regimes to see “how best they can continue to support housing policy objectives”.

The minister also said he intended to review the use of the Section 110 regime and that he would establish a working group to consider the taxation of funds, life assurance policies and other investment products.

There was little detail about what type of reviews he was initiating, or why he had decided to announce them.

When Ian sat down with the minister on Friday for their annual post-Budget interview with The Currency, he asked him whether he was concerned about some of the activities of the funds.

Donohoe was unusually vague in his response:

“It’s not driven by a concern, a specific concern – but it is driven by the fact that, if these are sophisticated and important tax regimes that we are creating, and if you don’t regularly assess how they are working, you can create other difficulties and challenges in the years ahead.”

There are vast sums of money involved in the various regimes. Investors have pumped €28 billion into Irish Real Estate Funds (Irefs), while the number of Section 110 companies has ballooned over the past year. Reits have fallen out of favour, something that is of concern for housebuilding targets. Plus, a review of the taxation of funds and life assurance policies could have big consequences for a large swathe of people.

So today, I want to examine the various issues about some of these regimes.

Irefs and Reits

Irefs are interesting. A relatively recent phenomenon, they were only legislated for in the 2016 Finance Act as a new tax regime for certain Irish regulated funds that invest, or intend to invest, in Irish real estate and related assets. It was part of government policy to entice international investors to Ireland.

If the company derived 25 per cent or more of its market value directly or indirectly from Irish land and similar assets, Irefs were subject to 20 per cent withholding tax, subsequently increased to 25 per cent, on defined “Iref taxable events” including distributions and redemption payments.

It is an investor-friendly scheme. The trouble, however, was that it was quickly gamed by investors. It soon emerged that a number of Irefs were being deliberately loaded with debt against assets, including sole shareholder and bank loans. This reduced their tax liability. This prompted Paschal Donohoe to tighten up the regime in 2019, when he introduced new anti-avoidance measures.

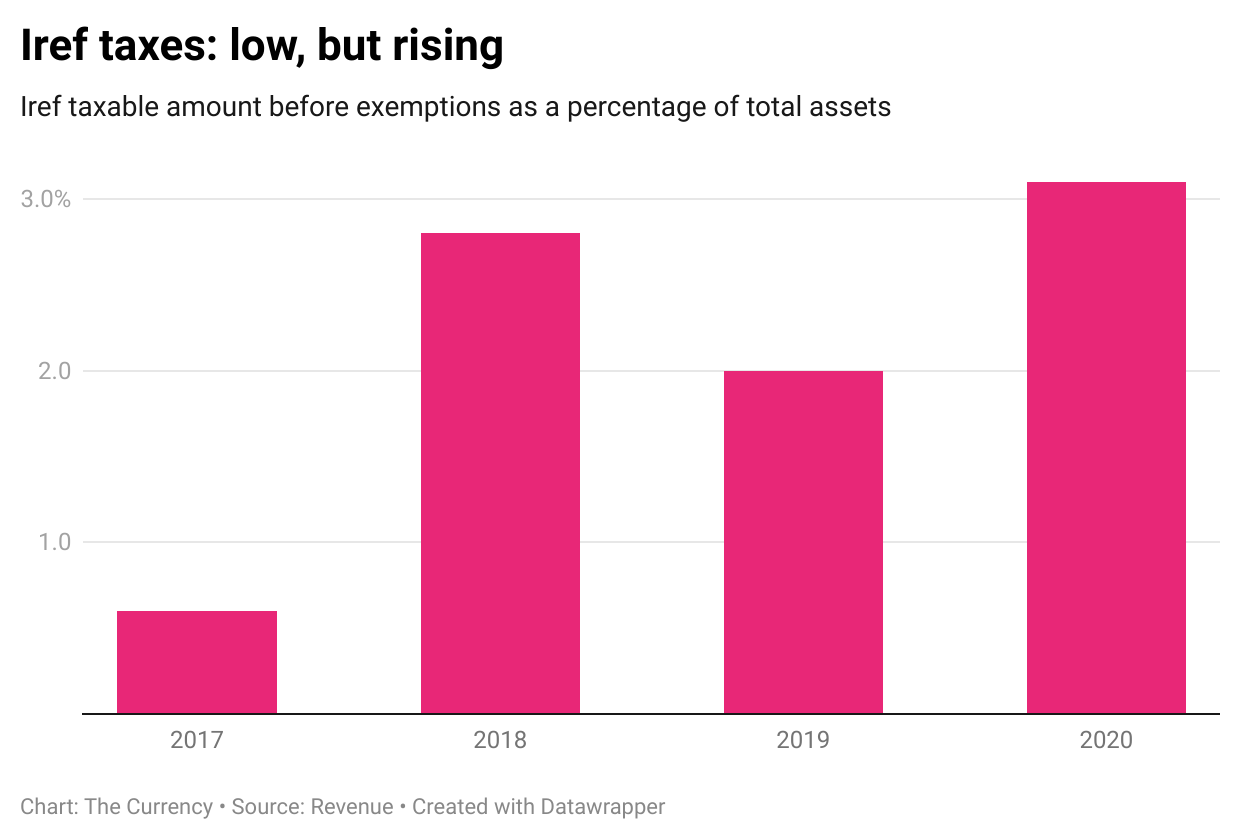

Revenue recently published data on how much tax Irefs were paying prior to the crackdown – and immediately after it.

This included data on Irefs’ taxable amount as a percentage of total assets, as shown in the above chart. The Iref taxable amount is before exemptions. In 2017, the first year that the regime was operational, the figure was just 0.6 per cent. The figure increased to 3.1 per cent in 2020.

So, just how much tax does this translate to? Again, the figure was low, but it increased after the loopholes were closed off. However, the number reduced last year, and this reduction is now being examined by the Revenue Commissioners. The fall-back could well have triggered the review.

Another reason for the review could be to direct the Irefs towards housebuilding. At the end of 2020, there were more than €20 billion of assets housed in Irefs. Of that, over there was €9 billion related to commercial property and €3.5 billion related to retail property. Just €3.4 billion related to residential property in Dublin, the real pinch point of the housing crisis.

The review of the Reit comes at an interesting juncture. One of the reasons that they have failed to capture investor appetite is the ongoing political uncertainty around them.

Despite record-high rents and housing shortages, shareholders in IRES have not really benefitted. Why? Well, as I have written before, the big risk associated with investing in IRES is that Sinn Féin come into power in two years’ time, and take away Reits’ tax advantages, and the thing ends up getting broken up and sold off.

Plus, the problem with Reits in Ireland is that having bought lots of properties at great expense, the stock market never valued the properties particularly highly. Hibernia traded at a 29 per cent discount to the valuation placed on its properties by independent appraisers prior to it being taken private.

Donohoe believes that Reits can play an important role in building houses housebuilding. At the moment, would-be investors don’t believe it is stable enough.

Section 110 companies

Section 110 companies are an IFSC structure designed to help legal and accounting firms compete for the administration of global securitisation deals. By 2017, it had become the largest structured finance vehicle in EU securitisation.

They have been highly controversial and were used by a string of vulture funds to make their tax bills disappear. This prompted a host of legislative measures in recent years. Despite this, the number of Section 110 companies has grown – from 1,335 in 2019 to 1,772 in 2021.

As the above graphs show, the amount of tax they are paying has been rising in recent years, but, interestingly, the tax as a percentage of net receipts fell in 2021.

Section 110 companies pay practically nothing in employment taxes – just €6.7 million in 2019 rising to €7.7 million in 2021. This is in sharp contrast to aviation leasing companies, which coughed up €291.7 million in employment taxes last year.

Politics

It remains to be seen whether the commitment to a review of the various regimes was designed to blunt an offensive by Sinn Féin, or whether it will lead to meaningful reform. However, given the scale of money involved, the various reviews by the mandarins in the Department of Finance should be watched closely.