It has been an eventful week on the multinational taxation front. On Monday, the multi-billion-dollar legal battle between Facebook and the US tax authority over the social media giant’s original transfer of intellectual property to Ireland in 2010 resumed before the US Tax Court after a two-year pandemic delay.

On Tuesday, Minister for Finance Paschal Donohoe and US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen discussed the implementation of the OECD global agreement, including a minimum 15 per cent corporation tax rate, just as intense negotiations continue between EU member states on its implementation here after a failed attempt by the 27 to agree on the details earlier this month.

Overnight, Yellen’s office had just released details of the White House’s 2023 budget, which proposes to go beyond the internationally agreed minimum rate and levy a 20 per cent tax on the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) of US-headquartered multinationals. That’s the profits located in countries like Ireland by Silicon Valley and US pharma giants in recent years, which have formed the base for the tripling of this country’s corporation tax take since 2014.

The difference – if passed by the US Congress, which is far from a done deal – would be a major one: At 15 per cent, Ireland remains a cheaper location to pay tax on an export centre than most jurisdictions offering similar business conditions and market access. At 20 per cent, this country loses its tax advantage over competing investment destinations, such as the UK and most of eastern Europe.

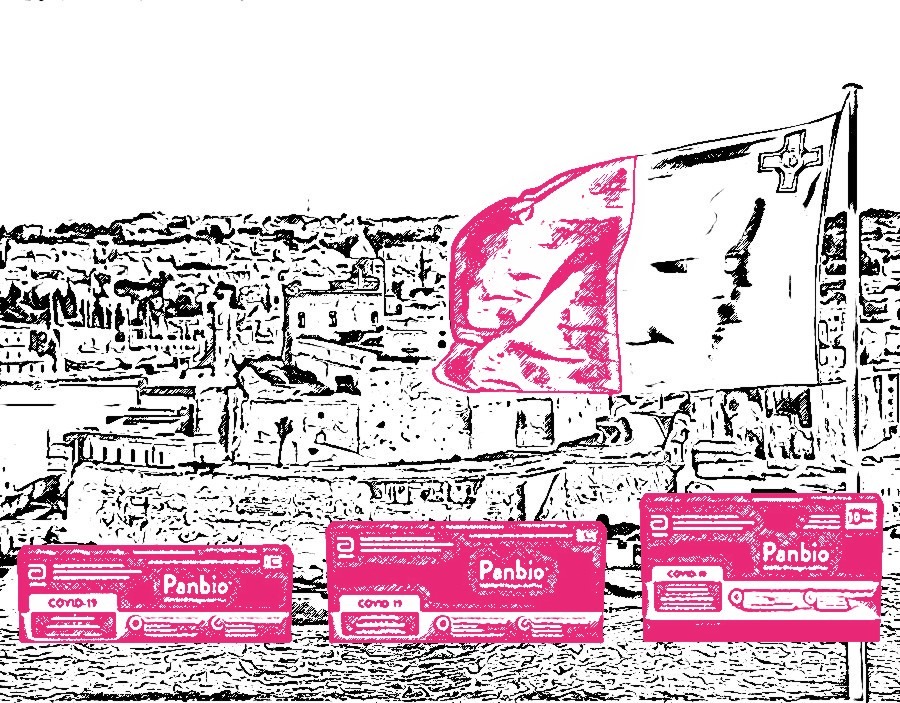

Meanwhile, here at The Currency, we have published a week-long investigative series in which Thomas forensically detailed how the double Irish and single malt tax schemes, both officially outlawed in recent years, have combined to survive in a new Frankenstein-like form straddling Ireland and Malta, which we have called the double malt.

The effective tax rates it achieves for multinationals – around 5 per cent, in line with Maltese legislation – are clearly unjustifiable in a world where all nations agree that the minimum should be 15 per cent. Yet the scheme is perfectly legal, as Revenue officials have confirmed to Thomas.

The next question is: Who is to blame?

First in line are the professional services firms that research, design and market turnkey corporate structures exploiting such loopholes. Some of the Irish subsidiaries we reported on this week have their registered address at the Dublin office of PwC, others declare their residency in Malta thanks to a set of rules in their constitution drafted across the Liffey by solicitors at Matheson.

Corporations themselves, of course, have a lot to answer for. The fact that an aggressive tax loophole remains available does not constitute an obligation to step into it. In the examples covered this week, Abbott Laboratories, Microchip, Tencent’s video games subsidiary Riot Games, and an aircraft leasing unit of Lufthansa chose to.

We have left others out of our coverage because, even though they did originally set up tax-minimising structures across Ireland and Malta, they appear to have given up on them since a tax treaty update between the two countries signalled an intention to close the gap in 2018 – however imperfectly. Healthcare suppliers Zeltiq (part of Allergan) and Merit Medical, for example, are in this category.

It is worth noting that Facebook, maybe informed by the ongoing US court case, has chosen to move intellectual property assets previously lodged in its double Irish structure back to the US. As Thomas pointed out yesterday, the truly significant employers on Ireland’s multinational scene appear to have finally given up on tax planning schemes as aggressive as the double malt, onshoring profitable assets in Ireland or in the US instead.

Yet the incorporation of new Irish companies with directors resident in Malta has continued at pace since the 2018 tax treaty update, and many have yet to reveal details of their activity. This will take time to transpire through company filings and reminds me of a previous discussion between Thomas and John Devitt of Transparency International on last week’s podcast, regarding the separate issue of Russian money flowing through Ireland. In both cases, the “many eyes principle” invoked by Devitt applies: The more people have free access to corporate information, the more questionable behaviour is likely to be detected and called out.

Their Irish-incorporated double malt subsidiaries, while shifting profits away from the reach of the tax authorities in Ireland and Germany, were used to collect subsidies from taxpayers.

The examples of Abbott and Lufthansa are particularly disturbing because their Irish-incorporated double malt subsidiaries, while shifting profits away from the reach of the tax authorities in Ireland and Germany, were used to collect subsidies from taxpayers.

Dublin-based Abbott Rapid DX International not only received €1.7 million in employment grants from the IDA, its business also exploded in 2020 because it became the international sale centre for Abbott’s Covid-19 antigen tests, whose customers were largely state agencies including those in developing countries. In an interview with Thomas, Christian Aid’s Conor O’Neill and Mike Lewis described the consequences of such profit shifting on poorer countries.

Lufthansa, meanwhile, placed 119 out of its 700 airliners in a group of three Malta-resident companies, two of which were registered in Ireland. The group leases those aircraft to its own airlines, with the corresponding profit emerging in Malta where accounts show they achieved a 6 per cent tax rate – instead of the 30 per cent typically applicable in Germany. When the Lufthansa group sought a €3 billion state aid loan from the German state to overcome pandemic lockdowns, it pledged the double malt aircraft holding companies as collateral.

The tension between the interests of the multinationals choosing to use such structures and those of taxpayers is evident. The consistent rubberstamping of legislation allowing this behaviour by the political parties in successive governments has become counterintuitive now that out-of-line loopholes such as the double malt demonstratingly shift the growing burden of taxation onto the individual voters politicians depend on for their re-election.

Yet as analysis by Stephen recently showed, even the most likely alternative to Ireland’s traditional government parties – Sinn Féin – has shown surprisingly little interest in departing from an economic model based on competing on tax for the largest possible inward investment by multinationals.

The tax treatment of those corporations is at the heart of the model Ireland needs to develop if it is to find its place in a rapidly changing world. The Currency has been covering this issue in depth since we launched two and a half years ago, and I have placed a selection of these articles on our Highlights page this week.

Stay tuned for more.

*****

Elsewhere this week, Francesca took a deep dive in the court papers lodged as part of Sonica’s examinership petition. The Co Dublin office fit-out company’s woes can be summarised in one word: Covid-19. This leaves room for hope.

I looked at the accounts of two of the most different Irish retailers you can imagine: the EuroGiant chain of discount stores and the jewellery group Anthony Nicholas. Once their figures are represented graphically over the past four years, their strategies have been remarkably similar – and successful.

And, as the war in Ukraine continued in a week marked by the summit between Chinese and European leaders, John Looby reflected on the elephant in the geopolitical room: Beijing’s role in the conflict.