Back in July 2020, more than 400 employees at the Cavan electricals specialist CG Power breathed a sigh of relief.

Its immediate parent was declared bankrupt in Belgium just months before, triggering a period of sustained uncertainty for workers at the company. However, supported by the growth fund MML Growth Capital Partners, management stepped in and acquired the business from the Belgian liquidators.

The company had been manufacturing in Cavan town since 1977, making transformers for use on electricity poles, electric car chargers, large-scale industrial plants, and solar power and wind farms.

In a statement announcing the deal, MML said the acquisition “secures the employment of its 400 primarily Cavan-based employees,” adding that it was “anticipated that the change of ownership will facilitate significant investment into the Cavan plant, something that has been difficult to achieve in recent years.”

Last month, a little over two years after the deal was announced, the majority of workers at the company, which has since rebranded as Kyte Powertech, staged two 24-hour strikes in an ongoing dispute over pay, with Siptu saying that staff “reluctantly” voted for strike action “only after pursuing every other avenue open to them in their efforts to secure a pay increase”.

The strike action came after workers rejected a recommendation from the Labour Court for a series of pay rises over a three-year period – 4 per cent from the start of this year (backed dated to January 1), 3.5 per cent next year, and 4 per cent in 2025.

The workers maintained the proposed pay increases will not maintain their standard of living amid soaring inflation, while Kyte Powertech argued that it could not afford to further increase labour costs beyond the Labour Court recommendation given the “challenging and uncertain business context”.

The Labour Court has since issued a further set of recommendations, including bonus payments and vouchers, a compromise agreed by Siptu and management.

It is easy to feel some empathy with both sides.

Kyte is a profitable company. In the year to the end of May 31, 2021, it made a pre-tax profit of €6.1 million – although €2.5 million of that number did come from a one-off exceptional gain arising from the buyout.

However, like many companies, it is exposed to a stuttering international marketplace – €38.7 million of its total revenues of €57 million were generated outside of Ireland. Management wants to keep costs under control to ensure the long-term stability of the business.

Staff, meanwhile, simply need more money in their pockets. Based on its 2021 numbers, the average salary for its 417 staff came to €32,900. And those employees are dealing with rocketing energy bills and interest rate hikes.

This is not an isolated case – and it is not just related to domestically owned businesses. Last week, I reported on a standoff between the US drug giant MSD and workers at its plant in Brinny, Co Cork.

Documents filed as part of an industrial dispute state that the relationship between the company and staff has “declined over the past number of years” and that a change of working practice at the plant has had “a devastating effect particularly when workers are facing a cost-of-living crisis resulting in inflation and soaring costs”.

Management, meanwhile, says that employees who do not wish to transfer to the new arrangements have been provided with the opportunity to avail of a generous redundancy package.

There are varying circumstances between the two companies, but there is a common thread behind both disputes and that thread highlights an emerging issue in Ireland at the moment.

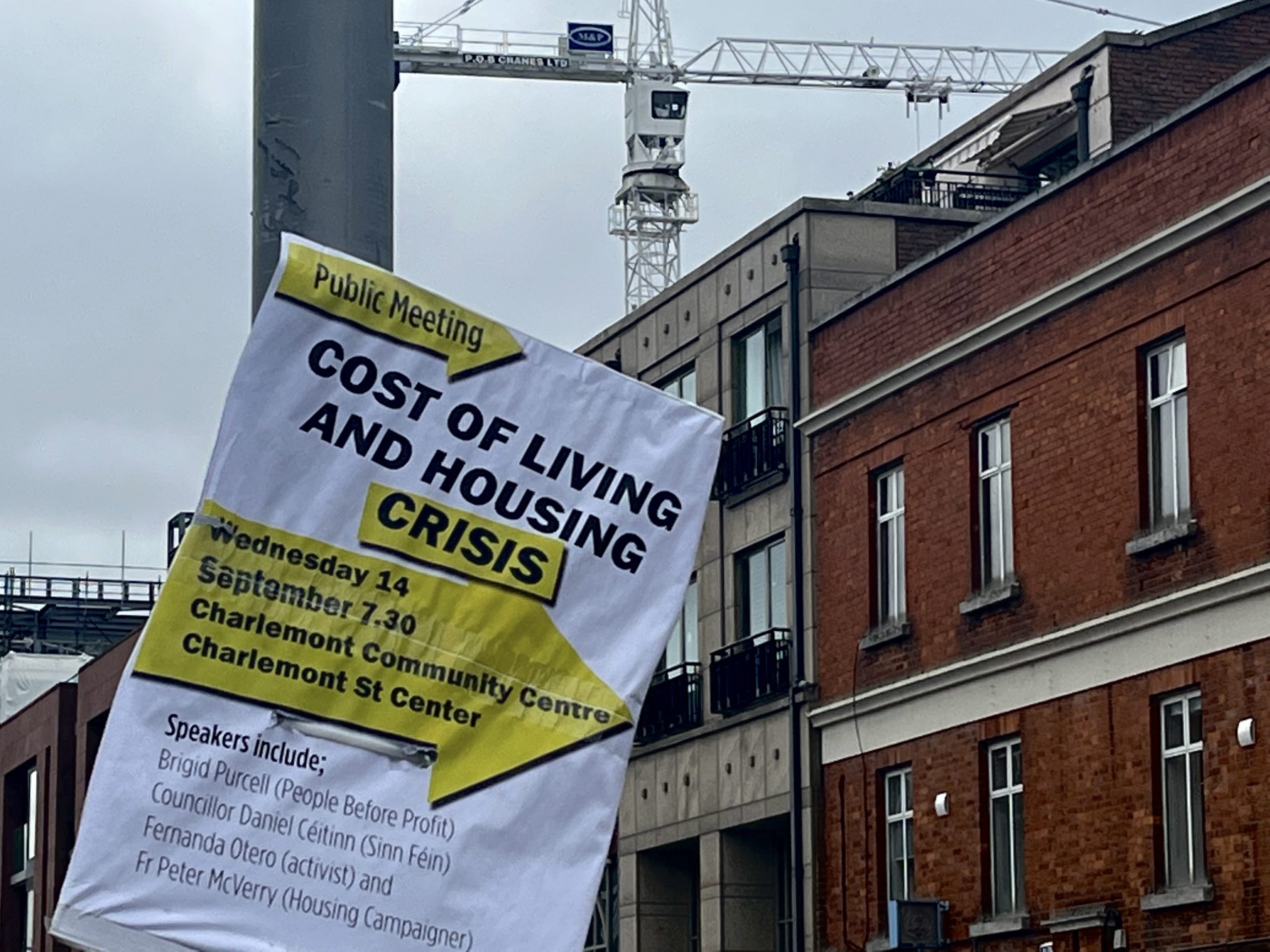

The cost-of-living crisis is set against the backdrop of major economic uncertainty – both internationally and in Ireland. At exactly the same time that companies are seeking to curb costs, staff are dealing with bigger bills and lower purchasing power.

This was an issue that Stephen dealt with in his column last week, which looked at labour trends. Pointing to the live-updating Indeed.com data on the Department of Finance’s webpage and the official vacancy rate from the CSO for the public and private sectors, he examined how vacancy rates have shot up post-pandemic, meaning employers are struggling to hire more workers at the given wages in their sector, thus bidding up the wages workers can command.

This would be a great moment for workers if inflation could be kept under control. However, as Stephen put it: “As it is, workers are being more expensive from the perspective of the employer at the same time as other major costs like energy are spiralling. Meanwhile, from the perspective of the worker, average wage increases of 4 or 5 per cent cannot compete with consumer price inflation of 8.7 per cent. Wage moderation in this situation will not work, and nor will cost control.”

The government sought last week to aid the lowest paid workers, approving an €0.80 rise to the minimum wage, bringing it to €11.30 per hour from the beginning of next year. No one can begrudge the lowest pay workers from an increase.

But most of those workers are engaged in retail and hospitality – two sectors that can arguably least afford them. Now off pandemic supports, a large cohort of companies in these sectors must engage with Revenue on warehoused tax debt.

The forthcoming budget will rightly be framed around the cost-of-living crisis. But it must not forget to assist businesses struggling to adapt and survive in the wake of Covid. As Stephen put it last week, we need to ensure that the cost-of-living crisis does not trigger a cost-of-employment crisis also.

*****

Elsewhere last week, over two days, Thomas revealed Hhow Ikea turned Ireland into a €30 billion home for retail profits. Part one examined how a few dozen staff running the Ingka Group’s internal bank and financial investment fund now manage over €30 billion in liquid assets – and counting. In part two, Thomas unlocked the retail giant’s Irish-operated investment strategy and explained how a number of subsidiaries in Ireland help reduce its overall tax liabilities.

Tom looked into Dylan McGrath’s plan to rescue one of his restaurants, reporting how shareholders, suppliers and the landlord of Brasserie Sixty6 are among the creditors expected to suffer severe write-downs while co-owner McGrath is preparing to lend fresh cash to rescue the business.

High construction costs are the bane of our housing system. New data sheds some light on what might be causing them. Sean explored the mysterious gap between the cost of homes and their constituent parts.

In a column on Wednesday, I argued that the government should now shutter the IBRC Commission rather than make it trawl through 37 other deals. After all, of the other 37 borrowers involved in the other transactions, 15 are companies incorporated in the United States, while 10 are companies incorporated in the UK. This means that 28 borrowers out of 37 borrowers are incorporated or resident in foreign jurisdictions, essentially outside the scope of the commission’s legislative power.

It raises the question why Enda Kenny and Michael Noonan made the curious and unexplained decision to extend its remit beyond Siteserv in the first place.